As Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi becomes deposed Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi, you can hear the familiar grumbling of skeptics in the US. They knew this would happen, of course. The Egyptian populace chooses to sacrifice stability and depose Hosni Mubarak, elects an Islamist president, realizes the error of its ways, and forces its democratically elected president to step down. And they’ve welcomed a military takeover? Damn. Well, the skeptics told us, didn’t they?

How the Ousting of the Egyptian President Is Like the Fourth of July

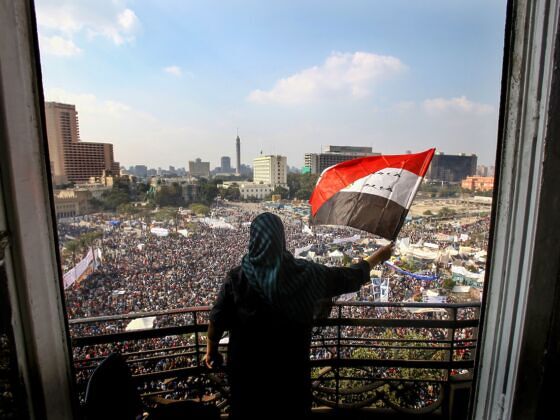

Try to explain that Morsi’s not just being deposed for simple political disagreements, but because he’s been a disastrous head of state who’s actually violated the young Egyptian constitution; that even former Muslim Brotherhood supporters participated in those massive protests; that Egypt isn’t clamoring for a military dictatorship so much as asking its one stable authority to maintain order while the nation figures its revolution out. Not only is this not without precedent (it’s very similar to the Portuguese Carnation Revolution, for example), but some see it as a sign of the sophistication and maturity possessed by a people who understand that there’s still much work to be done and that there are ways to do that work without having the country explode into a full-on civil war.

This, the skeptics will tell you, is nonsense. The proof is in the roz bil laban, after all: January 25, 2011, was a long time ago. This is a failed revolution.

And here the skeptics will have invited some much needed perspective, bolstered by our own preparations to celebrate revolution in the United States.

When we celebrate independence on July 4, we commemorate the 1776 adoption of the Declaration of Independence, not the birth of a nation sprung fully formed from the heads of its founders. The Revolutionary War didn’t end until 1783, and the Constitution wasn’t ratified until 1788. Many veterans of the revolution turned against its leaders for reasons as lofty as ideological opposition and as mundane as docked pensions. Government officials encouraged rebellions and engaged in duels. Organized, armed insurrections took place well into the 1790s, followed by skirmishes with the revolution’s main financial backer, France.

The US sort of started to look like an autonomous, unified, self-sufficient republic after the War of 1812 ended in 1815, but only if one ignores the constant fighting that continued to plague the nation due to expansion, mistreatment of Native Americans, conflicts over slavery, and the dueling visions of Northern and Southern elites.

So we had a whole lot of fighting leading up to the Civil War. Think about that for a moment: The United States had ongoing, armed conflicts within its national borders long before the Civil War, leading up to that most deadly conflict, which was essentially still a hashing-out of unresolved disagreements which were present even before July 4, 1776.

So if you find yourself tempted to dismiss Egypt’s revolution because it’s hitting obstacles in its early years, step back for a minute and consider that the national identity we’re celebrating today looked absolutely nothing like what we understand it to be until almost 90 years later than that illustrious date from which we typically start counting.

Are there reasons to be apprehensive? Of course there are, and there will most likely be more missteps, inadequate stopgap solutions, and even full-blown disasters. But revolution’s a messy thing and the people of Egypt are working on it. Hell, we’re still working on it. Lacking complete and perfect understanding of all aspects of someone else’s situation, we might do well to err on the side of hope. We might give people a little more credit and a little more time before counting them out. We might try to understand that their current struggle is exactly the type of thing we claim to be celebrating right now.

So to my dear, dear friends in and of Egypt — to all people everywhere struggling for a better, freer existence, no matter how imperfect that struggle may be — I send all of my love and my best wishes on this Fourth of July.