WE’D BEEN PATIENT MOST OF THE DRIVE. But somewhere around the 6th hour across North Carolina, having dropped from the highlands to the Piedmont to the coastal plain, past the damp winter fields of cotton stubble, past the endless stretches of pine flatwoods, the kids were getting restless. Nobody could wait to reach the Outer Banks.

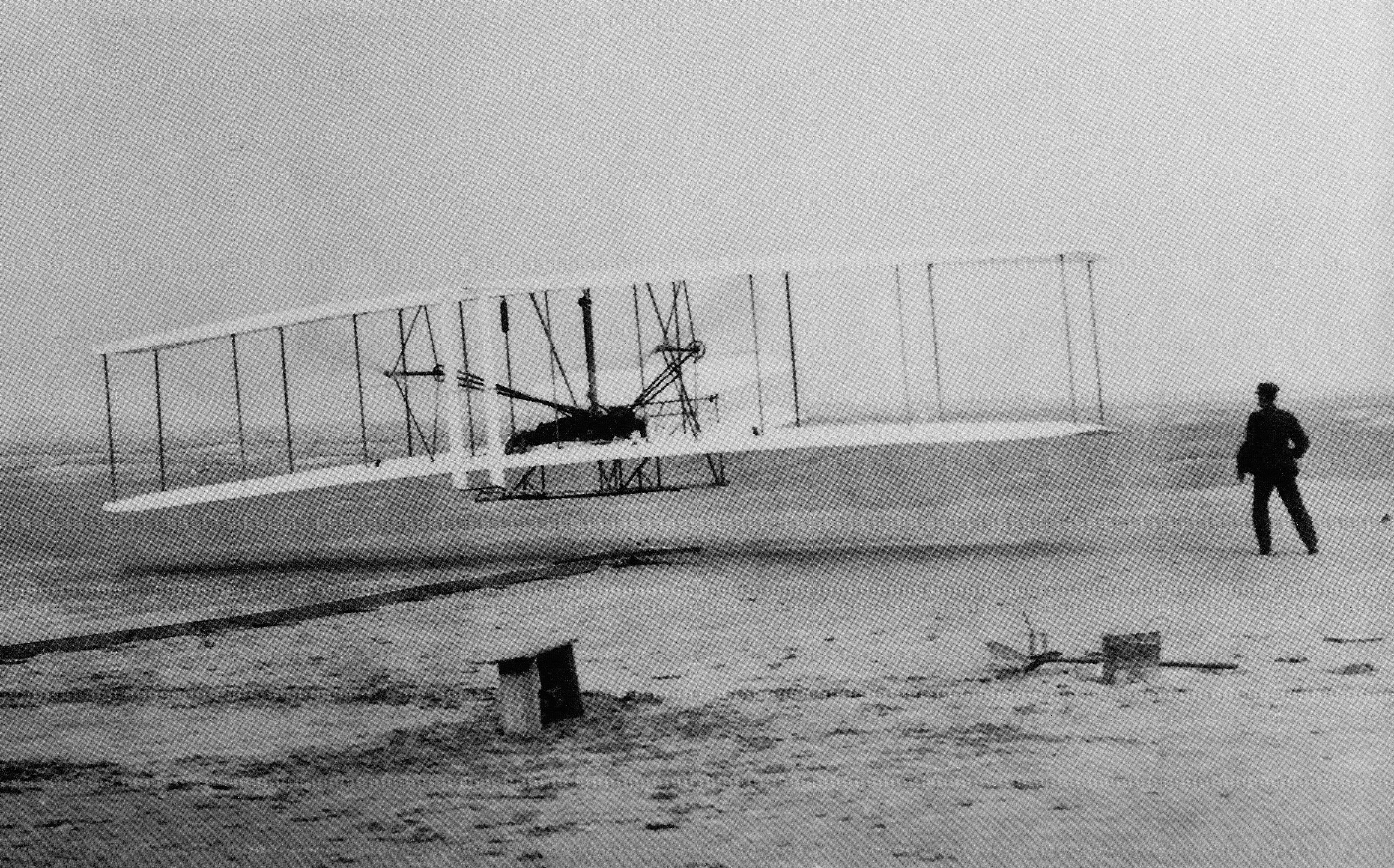

We’d been preparing for this trip. I checked out books on the Wright Brothers, who had become funny-hatted characters in my kindergarten-aged kids’ stories. I wondered how old Orville and Wilbur would’ve perceived this road on their first trip from Dayton in 1900. What levels of anticipation must they have had in these last couple dozen miles?