Entering a place

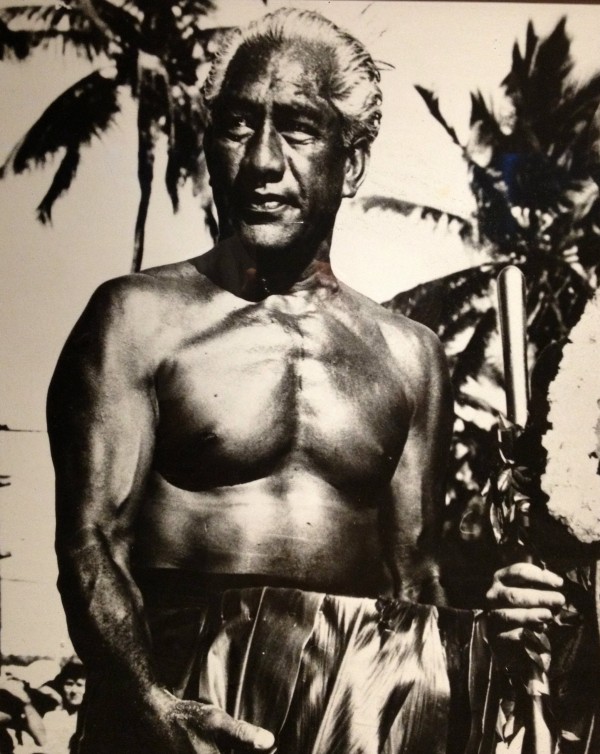

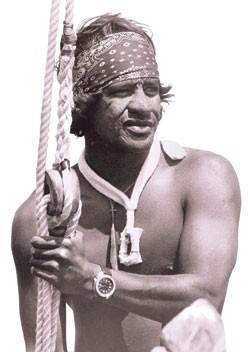

Tutu Janet, beloved ukulele player and elder at Turtle Bay. Please enjoy listening as you read.

DRIVING THE H2 freeway across Oahu — empty at 11pm — I had the sudden realization that to arrive at night for your first time in Hawaii is like a gift.

As travelers, we’ve become conditioned to Instagrams, to filtered images of place. Better to start out seeing only dark contours of mountains and passing flashes of road signs. Better to roll down the windows and take in this new air — tropical and warm but light, not muggy — the air of vast open Pacific space. Better to scan the local radio — some slack key guitar, reggae on Da Paina, electronic music on KUTH — all of it settling you into a strangely calm alertness, a heightened level of noticing, a reminder that entering a place — perhaps the most important moment of travel — shouldn’t be a head trip or playing out of expectations, but very much a bodily act.