THE MENTOR – Cardigan sweater and glasses, endless supply of coffee and biscuits. Because every adventure needs a nice old lady to send you on your way.

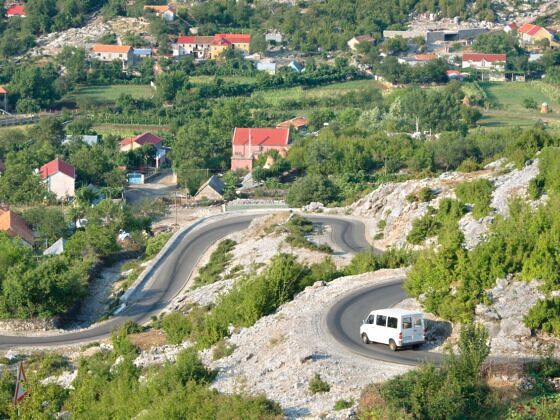

“It’s no problem,” the B&B proprietor told me in her thick Albanian accent. “Buses for Tirana leave every hour.”