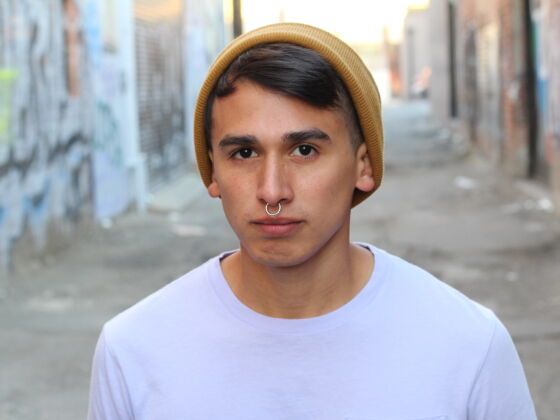

José G. González aka the “Green Chicano” is an educator, environmentalist, artist and the founder of Latino Outdoors, an organization which serves as a storytelling platform for defining the ambicultural identity connecting Latino communities and the outdoors, among many other functions. Latino Outdoors exists to connect cultura with the outdoors.

Bani Amor: Tell us about yourself. How would you describe your work?

José G. González: I would say I’m Mexican by birth, Chicano by identity, Latino by culture and Hispanic by census count. An educator by training, illustrator by interest, and conservationist by pursuit. I’m very much a mestizo and ambicultural in many ways.

What that looks like now with the Green Chicano identity and Latino Outdoors is to work on the storytelling of what these identities mean/look like and what they say about carrying these identities in relation to outdoor spaces, nature, and conservation.

So when I’m admiring the beauty of Grand Tetons National Park, I’m also thinking about the history and culture of the space in relation to who’s there, who’s not, and why that may be. I look at natural spaces with the eyes of a naturalist, artist, and historian.

Bani: Amazing. How did Latino Outdoors come about?

José: Latino Outdoors came about with several threads. During college I was an instructor for an outdoor program specifically for migrant students in CA, mostly Latino and English Language Learners. As a teaching team we traveled throughout the state and saw all these amazing outdoors spaces, from the desert to the redwoods, and I noticed how rare this “work” was in terms of the instructors, the students, and the places we were working. I thought, “Why aren’t there more programs like this?!” Basically, where are all the Latino outdoor professionals in this field and how they connect? How do they know about each other? Because I wasn’t finding them.

That experience further connected me to the outdoors and after teaching for a few years I went to get a Masters in Natural Resources & Environment. And the question was, where are the Latino-led and Latino-serving organizations in the environment and the outdoors? Especially those that are not framed solely around environmental justice. It was then that an instructor from the same migrant outdoor program asked, “José, I want to pursue this as a career, who do I talk to? Who do I connect with?” And I didn’t have a great answer for him, I didn’t have a community to connect with. And it made me think of visiting all these state parks and national parks and remembering how awesome they were but how much of a privileged opportunity they were in many ways/cases.

Lastly, I was asking people to tell me where to find this unicorn of an organization and they would tell me, “Great idea, tell us too!” So I thought, well, let’s do it!. Because there are a lot of stories, travelers, and programs that I know are doing great work, but we don’t really exist in a community or are connecting with a shared identity.

Bani: What do y’all do?

José: We center around 4 things.

1. The professional community.

We want to identify, connect, and amplify the leadership infrastructure of individuals that exist with this identity. They bring their culture on the trailhead and they use it in positive ways to connect their work as conservationists/ outdoorspeople with the community. I’ve found many that say, “I’m the only one doing this work…” and I want to say “You’re not, let’s exist and collaborate in community. Let me share with others the awesome stuff you do.”

This community is a precious resource that allows us to get to the other three things.

2. The youth.

Beyond just getting youth outdoors, we want to show them that there are role models and possible mentors in this field for them so that they can follow in this work knowing that their culture is an asset and that it’s valued in this field. We’re also finding that youth in their 20’s are the ones that naturally want to connect with Latino Outdoors, that they are looking for ways to have their culture be positively represented in the outdoor experiences they already enjoy.

3. Family.

We want to showcase the value of family and community-oriented outdoor experiences because it connects parents with their kids and it naturally taps into how many other communities like to enjoy the outdoors beyond the solitary backpacker. We do this through day hikes, outings, and other events partnering with parks and conservation orgs.

4. Storytelling.

We wrap this all together by finding ways to say, “Yo cuento” — to show what the story looks like as a Latino/a in relation to the outdoors — and how diverse that is in terms of identity and experiences. We have “Xicano in the Wilderness,” “Chicano in the Cascadias,” “Chasquimom,” and so forth — people identifying in many ways but highlighting their culture in the outdoors. We’re doing this through interviews, narratives, social media, and just starting with video.

Bani: Awesome. What are some strategies you’ve found effective in inspiring urban-dwelling Latinos to care about conservation issues and to also get out into the outdoors?

José: Good question. The “urban Latino millennial” is one demographic that is high on many lists for parks and open spaces. Which is no surprise, since they like to be out in a group with a social experience. It can be shared through social media or at least documented with a smart phone. But we know that it’s also a matter of how the outdoors in your community is viewed and supported. How your local park is a connection to outdoors farther way.

People can identify with a well-known national park farther away and not know they have a fantastic national wildlife refuge nearby. So one thing is to just go, let the place speak for itself and show each other how accessible all these places are. Then once we’re there, we have the programming be flexible so that we learn as much from the community as we want to share. So it’s a not a lecture about the outdoors or a class in conservation.

I may say it’s like learning English if you only know Spanish. We don’t want you to not know or use Spanish and have it be replaced by English. Same with the outdoors. What is the language you already know about these experiences? Tell us! and we’ll share “new words” to add to that. It makes it challenging, exciting, fun, and so rewarding.

Bani: That’s amazing. Using that analogy of language-learning, I think that it’s more like remembering a language that we were taught to forget. For me, communities of color being separated from nature is a part of the process of colonialism.

José: Exactamente! That can be hard for many people and there is a lot of anger and hurt that sometimes comes out, but I keep my hand out to people to say, I understand. Especially if you are “Latino” and you have a history of colonizer and colonized. Many public lands in the Southwest used to be land grants that were taken away from Hispanos and Chicanos. But those lands themselves were carved up from indigenous communities.

Bani: I wonder how Latinos in the U.S. can connect to the outdoors while also confronting our place as both settlers on indigenous land and displaced mestizos from our own lands across Latin America.

José: It’s both a complex and simple process but it takes time and understanding. I find that people, and especially young people love to connect to their culture. Especially in college when they take a Chicano studies class or the like and they say, “Wait, how come nobody told me about this?!” I use that frame to share how there are many reasons to be proud of our history, and especially with our traditions and heritage of conservation and the outdoors.

We have it, but often need to rediscover it, and much of it comes from our indigenous roots. So we elevate that as much as it was torn from us or as it has been forgotten. But a reality is that so many of us are mestizo and that has been a process too. Indigenismo did not just happen. People looked into their history and said, wait, there is a lot to culture and tradition here that we tried to get away from thinking that just European values were the way to civilization.

Bani: Yup, it goes back to education. We’re kind of forced in this country to adhere to the popular immigrant narrative — we came here for a better life, etc. — instead of learning how we were really, a lot of the times, displaced politically and ecologically.

José: So I say, are you proud to be Mexica? Did you know they strived to be a zero-waste society? Yeah.

Bani: You came up with this word, “culturaleza.”

José: Yeah, that’s another example of mestizaje. Connecting cultura and naturaleza to show that the separation of people and environment is one frame and often one that alienates many of the communities that many conservation organizations want to reach. One perfect example is food. Food is a cultural trait that is with us all the time from when mom and grandma made tamales and nopales at home and when we’re looking for the right taqueria.

So if we’re having an outing in the outdoors, instead of me just saying “I’ll bring the sandwiches, or let me run to Trader Joe’s” (which I do anyways, jaja) we try to ask people to make it a potluck and they love bringing something they like and want to share. Some favorite memories of mine are having nopales, tostadas, and mole in the sequoias with moms that love to cook that at home.

Bani: That’s what’s up.

José: People have asked, why “Latino Outdoors”? Isn’t that exclusive? Or, isn’t that giving in to a colonized identity? I say that I intend for it to be an INCLUSIVE starting connective point. It’s to bring in communities and people that maybe we haven’t reached out to let alone just expect them to join in and be valued in this space. And we are open to all “shades” of Latino including those that stress nationality, or being Chicano, Hispano, and so forth. Because one thing that can connect us besides often having shared Spanish/Spanglish language is that we also have a connection to land and space in our roots, and that is important.

Bani: Word.

José: Ah, and to make sure we are kind to each other, because in some of these beautiful spaces are ugly human experiences. Very short: while visiting Grand Tetons National Park, we once stopped at a small town for ice cream and I was given one of the worst looks of “You’re not welcome here” that sticks to me to this day. So yeah.

Bani: I know that look very well. Our presence in natural spaces is radical.

José: Bien dicho.