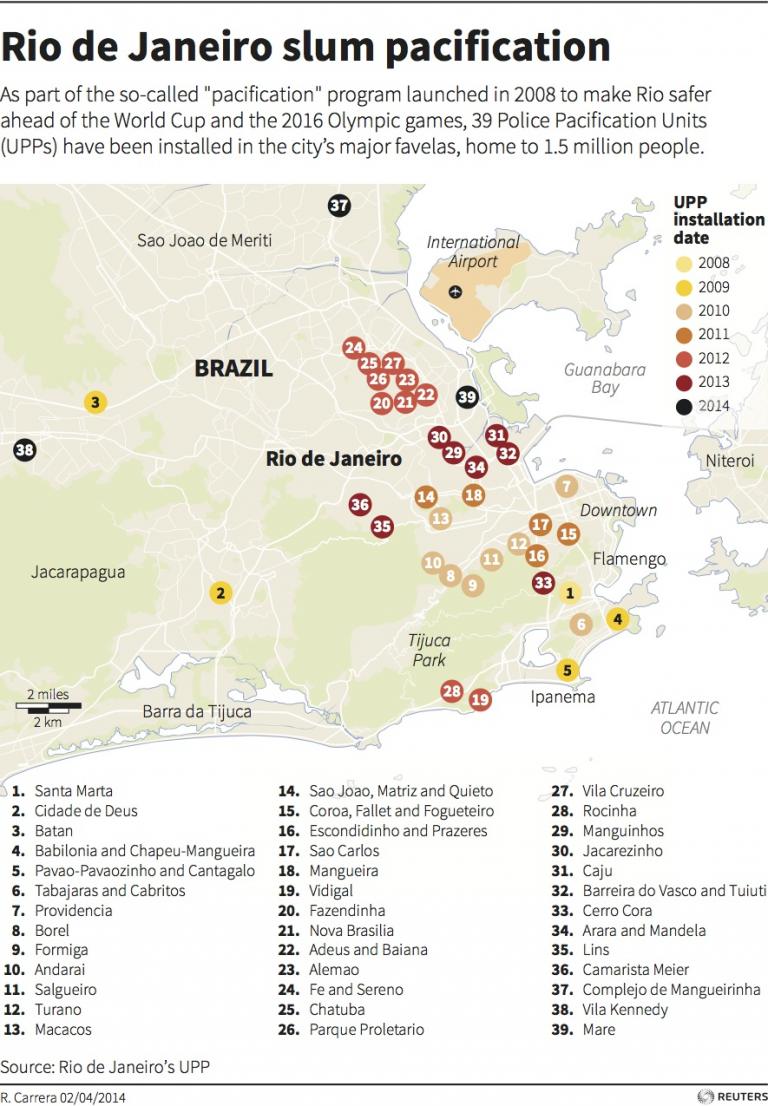

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil — If you already follow the news out of Brazil, there’s something you’ve probably seen mentioned a lot: Rio’s “pacification program.”

If you haven’t been watching Brazil, it’s worth paying attention now to the revolutionary policing project happening in the city that will host this year’s Summer Olympics. As communities around the world discuss how best to police and protect marginalized communities, Rio is eight years into a radical approach to policing its most crime-ridden favelas — one that involves actual invasion and occupation of neighborhoods by cops.