I HAVE BEEN researching Tongan tattoo traditions for the past 15 years. In 1998 I began tattooing, primarily doing a mixture of Polynesian styles. I wasn’t too familiar with specific Tongan tattoo patterns because there was little knowledge of them, and only several sketches produced prior to its outlawing existed.

I began asking my parents, aunts and uncles, and other family members. The more I asked the more I realized that many of them knew traditional tattooing was once practiced, but preferred it not be resurrected because of Christian values. However, in my early days of tattooing I also encountered many Tongans eager to get tattooed and delve into that part of their history.

Many had stories that they overheard in family discussions and kava circles. These stories ranged from uncles being tattooed in Samoa, to remembering grandmothers having marks on their bodies resembling more traditional tattoos than anything Western. My interest sparked further, and I began learning anything I could about this ancient tradition. My research led me to uncovering many sources of early writings as well as information from Tongans themselves.

In early 2002, Suʻa Suluʻape Alaivaʻa traveled to HawaiʻI to tattoo Samoans with traditional malofie as he had done for years. Several Tongan individuals met with Suʻa and began the process of reviving the traditional Tongan tatatau.

After about 8-10 sessions, the first two Tongans in over 150 years bore the marks of their ancestors.

Ataʻata Fineanganofo was the first Tongan tattooed by Suʻa Suluʻape ʻAisea in San Francisco. Here he is dancing and celebrating after the completion of his tattoo and traditional blessing.

ʻAisea apprenticed under Suʻa Suluʻape Alaivaʻa and was ordained with the Suluʻape title, later receiving the Suʻa title, which allowed him to conduct the traditional blessing and entitle individuals. I started my apprenticeship under him in 2010.

Tattooing has long been a part of Pacific Island cultures since the first island communities arose. Various traditions tell of different ways in which tattooing was born or brought to each island. Other stories tell of cultural heroes and gods who propelled tattooing into spiritual and political realms. But most importantly, tattooing for islanders was a unique mark signifying their inherent role within the society that raised them.

In Tonga, tattooing was a vibrant part of the culture until the early 1800s. At this time, Tonga underwent radical political and religious changes with the arrival of Westerners. Tonga was also facing a civil war that would eventually uproot longstanding chiefdoms spread throughout the Tongan archipelago.

The conversion of Tongan chiefs to Christianity, and the unification of Tonga under a single monarchy meant the destruction and eventual obliteration of many traditional practices. Though some traditions were spared, those that had a direct connection to the old gods, body ornamentation, and open sexual and ritual killing practices were quickly outlawed. Tonga was rapidly adhering to the impending Westernization of the world.

The traditional Tongan word for tattooing or skin marking is made up of two words: ta – to strike, hit, or tap; and tatau – same, similar, symmetrical, balanced.

Poetically, tatatau inferred a symmetrical balance achieved through rhythmic beats. Tatatau was a specific tradition that was both home-grown and influenced by other Pacific Island cultures. The origin story of tattooing in Tonga tells of a young chief who saw the practice in Fiji and was given tools with a chant instructing him to “tattoo the women, and not the men.” Once in Tonga, the young chief struck his foot violently on a rock and mistakenly reversed the order of the song, thus marking the men and not the women.

Tonga’s history is full of maritime voyages and intermarriages between island chiefdoms. This brought many external influences into Tongan society, as well as exporting many local customs into other island communities. Tattooing was an art that was heavily influenced by these maritime exchanges, most notably with Samoan tattooing.

Samoa had a unique tradition that elevated tattooing to one of the highest symbols of manhood and societal reciprocity. In Tonga however, tattooing appeared in multiform fashions, ranging from tattoos of Tongan origin to those similar to a Samoan malofie, as well as markings that expressed similarities to Uvea, Rotuma, and Fiji.

Tongan commoners were tattooed in Tonga by tufunga tatatau. The role of tufunga tatatau in Tonga was not an inherited role. Individuals who were skilled in this art form could seek apprenticeship from a tufunga tatatau to later become recognized as a master tattooist.

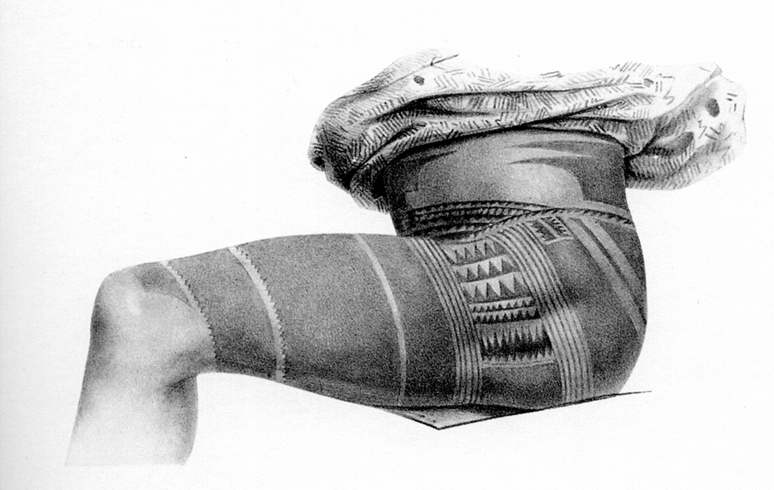

The author's tattoo is pictured above. Click for a larger view. Using or appropriating these designs without permission is not okay. You shouldn't do it.

Young Tongan males were usually tattooed by their mid to late teens. Tattooing became a necessary part of becoming a Tongan man and women would consider an untattooed man less desirable. Young men were often taunted and teased by their peers for not being tattooed as well.

Specific tattoo artist guilds existed in Tonga prior to its outlawing. Most often, tattoo patterns were discussed with the individual and their families and were marked unceremoniously. A majority of these tattoos were between the waist and the knees. This specific body placement was common amongst Polynesian and Micronesian island communities. The process would take months or sometimes years to complete, and tufunga tatatau were paid for their services with traditional goods such as clubs, mats, bark cloth, and other traditional fine arts.

The most notable tattoos were the ones worn by chiefs. Tonga is a highly stratified hierarchy of high chiefs, lesser chiefs, and commoners. Commoners were not allowed to touch a chief’s body, articles of clothing, or food unless they had an inherent duty associated with carrying out one of these restricted activities.

Tattooing high chiefs was one practice performed only by non-Tongans. Most often a tufuga from neighboring Samoa performed this service. Samoan tufuga tatatau were revered for their sacred duty of only tattooing high-ranking individuals. Tongan chiefs of the Tuʻi Kanokupolu clan traveled often to ʻUpolu and Savaiʻi to get tattooed. Prior Tongan monarchs associated with the Tuʻi Tonga and Tuʻi Haʻatakalaua were rarely tattooed. Some chiefs were noted as having been tattooed, but it was not known by whom.

Although tattooing was outlawed in the 1800s, many chiefs continued to travel to Samoa to get tattooed. Additionally, Tongans who could travel and afford the cost would also travel to Samoa to get tattooed. This occurred as late as the 1950s, but eventually died off through the 1970s and 1980s.

In the 1990s, tattooing in the Pacific saw a renewed interest amongst island youth and communities attempting to revive and revitalize ancient traditions. A new sense of pride in being an islander meant marking their skin as their ancestors did. Many islanders began wearing traditional island designs consisting of arm and leg bands.

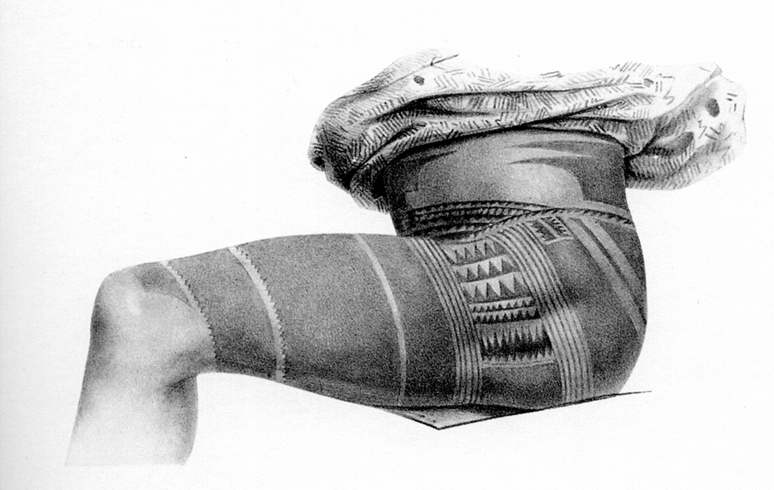

Micah Tiedeman, pictured above, was one of the first two Tongans to wear the traditional tatatau. Click for a larger view.

Eventually, the interest grew and island tattooists began experimenting with mixing island designs together to create contemporary Polynesian style tattoos. The fad has grown worldwide with Polynesian style tattooing becoming a genre of the tattooing community at large.

In 2010, Suʻa Suluʻape ʻAisea was invited to Tonga to demonstrate tatatau at a yearly cultural arts convention. During his visit, ʻAisea tattooed several individuals using traditional tools and was afforded the opportunity of tattooing members of the royal family. This occasion was momentous for us as tattoo revivalists since this was the first instance of traditional tattooing being performed in Tonga since the 1800s.

ʻAisea has expressed that his ultimate goal was to establish traditional tattooing in Tonga by institutionalizing the practice within the village environment. 10 years ago this would have been inconceivable and considered impossible by most Tongans. Yet since the resurgence, Tongans have come to accept the ancient practice of tatatau in Tonga.

Today, there is great in interest in Tongan traditional tattooing practices and several other Tongan tattooists, including myself, have begun apprenticing with the traditional tools. The tools have been constructed as they were in the traditional times, made of bone and turtle shell. The markings have been outlined and revived with great thanks to Suʻa Suluʻape Alaivaʻa’s knowledge of traditional tattooing. Several Tongans showing a profound interest have also worked collaboratively to disseminate the knowledge and help move the revival forward in song, poetry, literature, and ceremony.

The evolution of the tatatau and its resurgence has also evolved to take on a deeper spiritual and cultural meaning for Tongans. The revived tradition has become a vaka, or vehicle, for reviving the past. Individuals who wear the markings serve as reminders for Tongans to hold close to their cultural traditions in the rapidly changing world. Ta Vaka has been adopted as the journey of completing the traditional Tongan tatatau. As the vaka once carried Tongans to far off destinations and served as the medium for manhood explorations, so too does wearing a traditional Ta Vaka symbolize that ancient journey from the past to the present.