[Note: This story was produced as part of the Glimpse Correspondents Program, in which ten writers and photographers receive a stipend and editorial support to develop two long-form narratives for Matador. The Glimpse Correspondents Program is open each fall and spring to anyone who will be living, traveling, working or studying abroad for more than ten weeks.]

I COULD LIST all of my belongings here: they pack away neatly into the small van that is the closest thing I have to a home in New Zealand. I don’t have much, but I do have time.

I have the time to boil water on a stove whose gas bottle is nearly empty, to hunch over a chopping board, cutting fruit into neat cubes for breakfast, to walk slowly and stop often. This past winter when night fell – early this far south – there was nothing to do except brew tea and read.

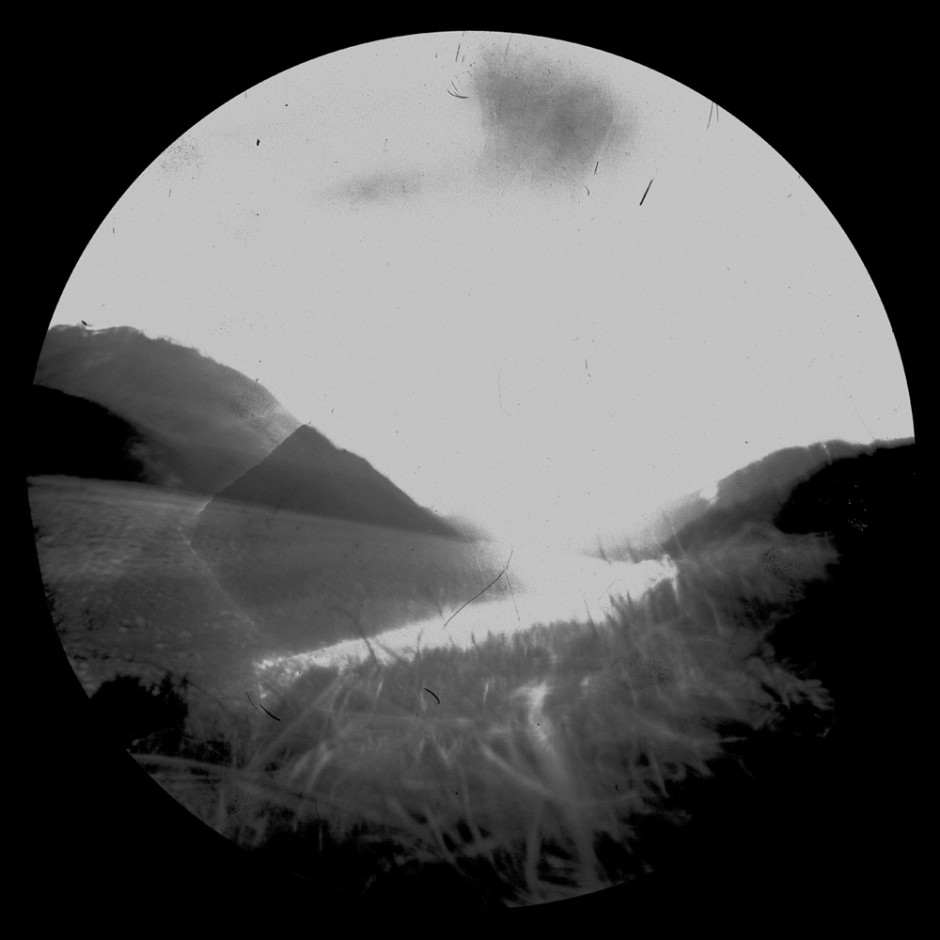

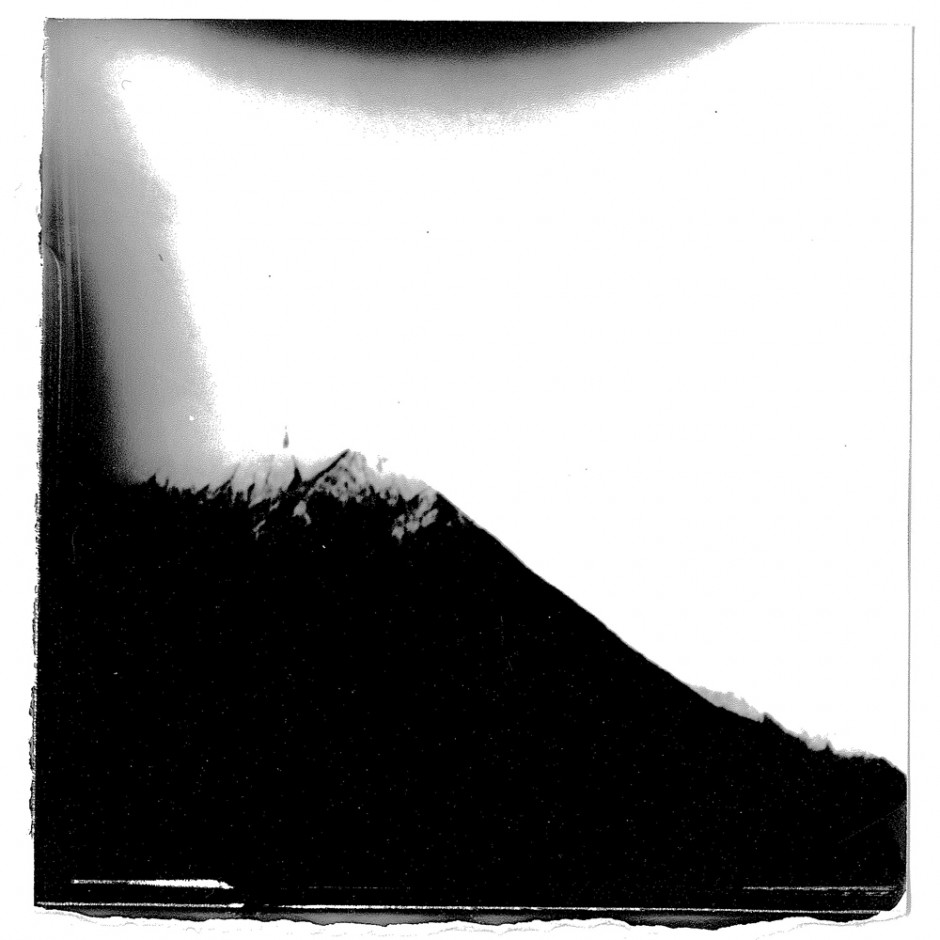

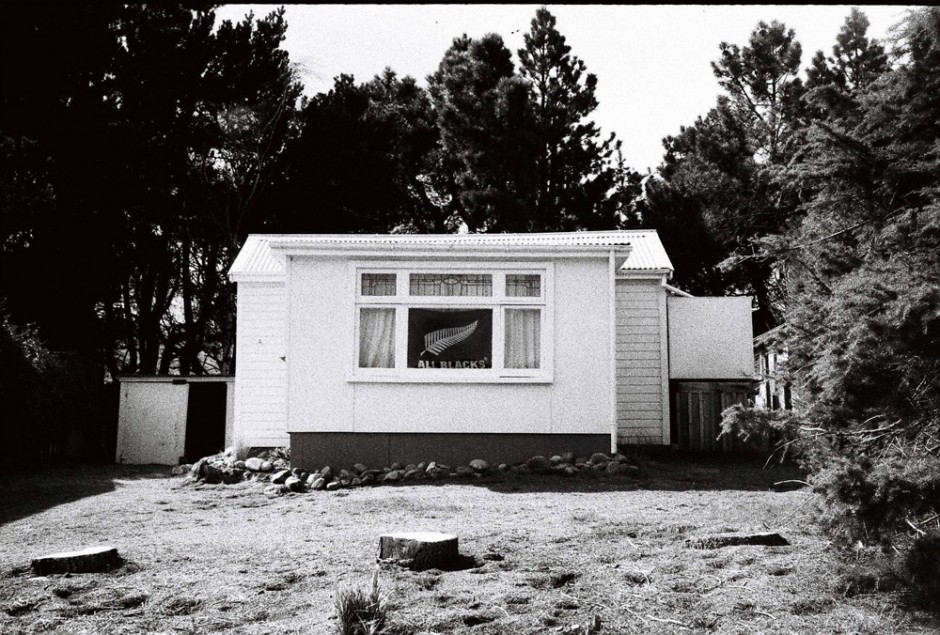

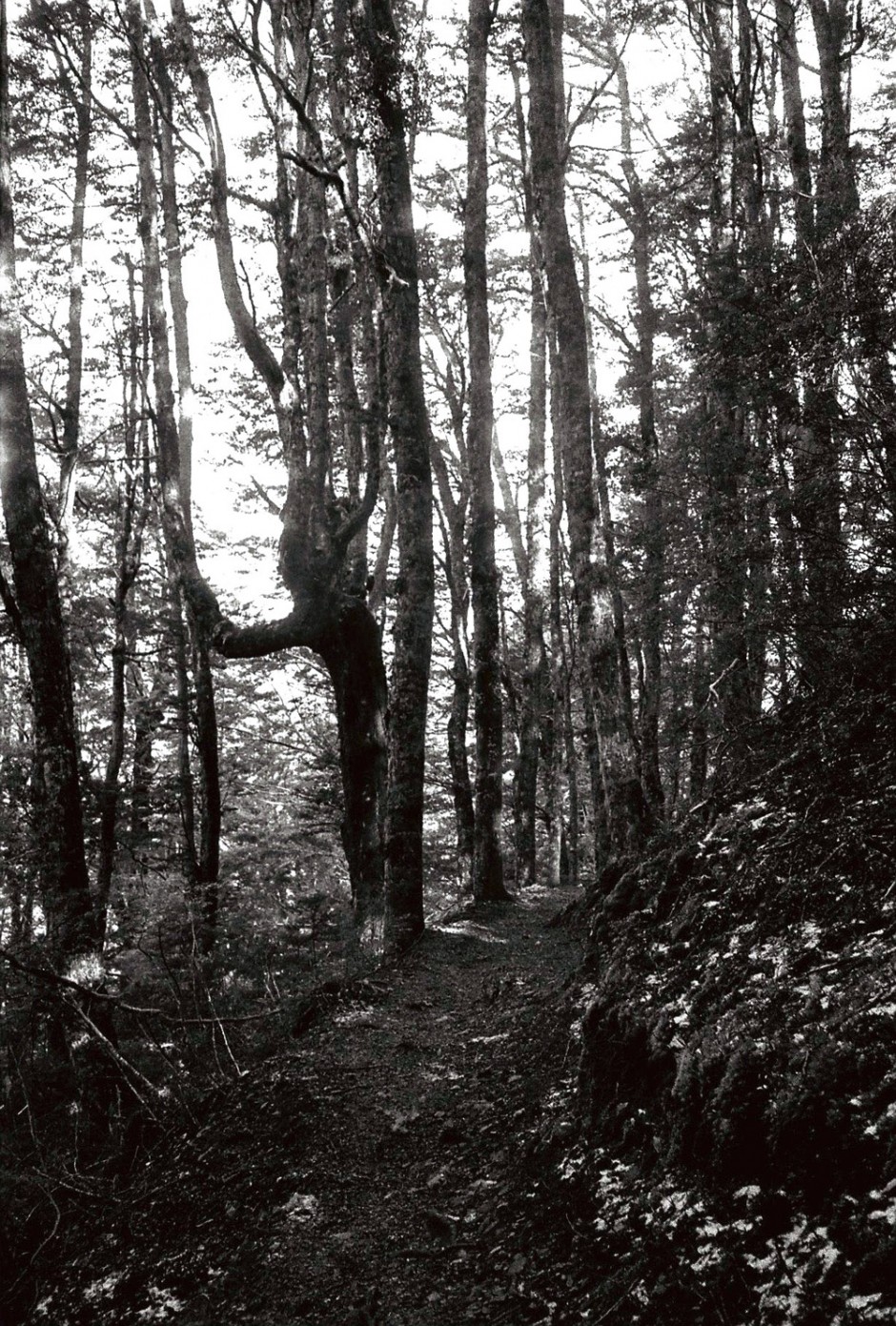

These photographs were made to reflect the value that I have found in the precious resource of time. They counteract our distinctly postmodern ability to capture and share images instantaneously, drawing out the image-making process as much as possible to enhance my awareness of the places that I have been. I wanted to avoid the ease of holding something at arms length and pushing a button: I wanted to sit still, to squint into a too-small viewfinder. I wanted to fiddle and twist and to stick things together with duct tape. I wanted to make it as hard and as slow as possible.

I started on the first day that my girlfriend and I arrived on the South Island, having rushed away from our last jobs, desperate to get back on the road and across the Cook Strait. In a second-hand shop in the tiny port of Picton I bought six battered biscuit and coffee tins for $10, before we stocked up with groceries and followed the coast road around the steep hillsides and clear waters of Marlborough Sounds.

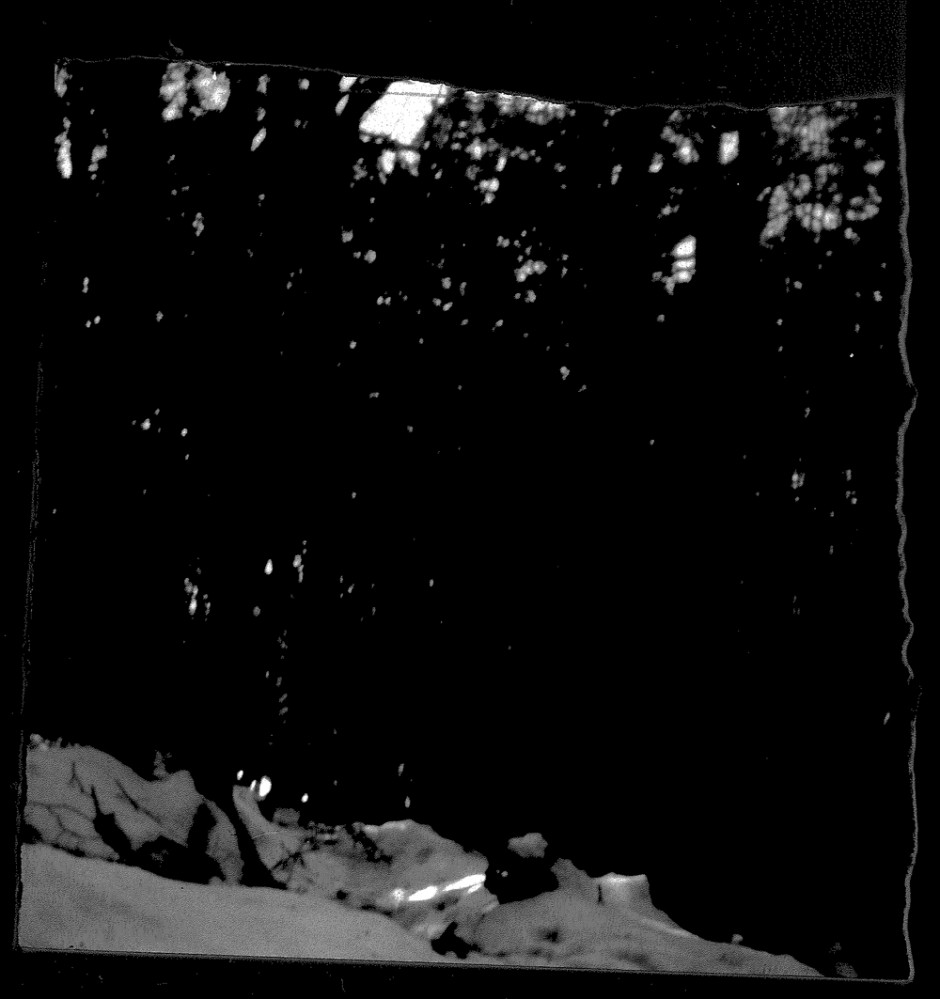

Parked up at the water’s edge the next day, I painted the tins black and made tiny holes in the bases to make rudimentary pinhole cameras. That night, working by the light of a torch wrapped in a red bag so as not to expose them, I tore photographic paper up to make negatives, wedging them into the lids.

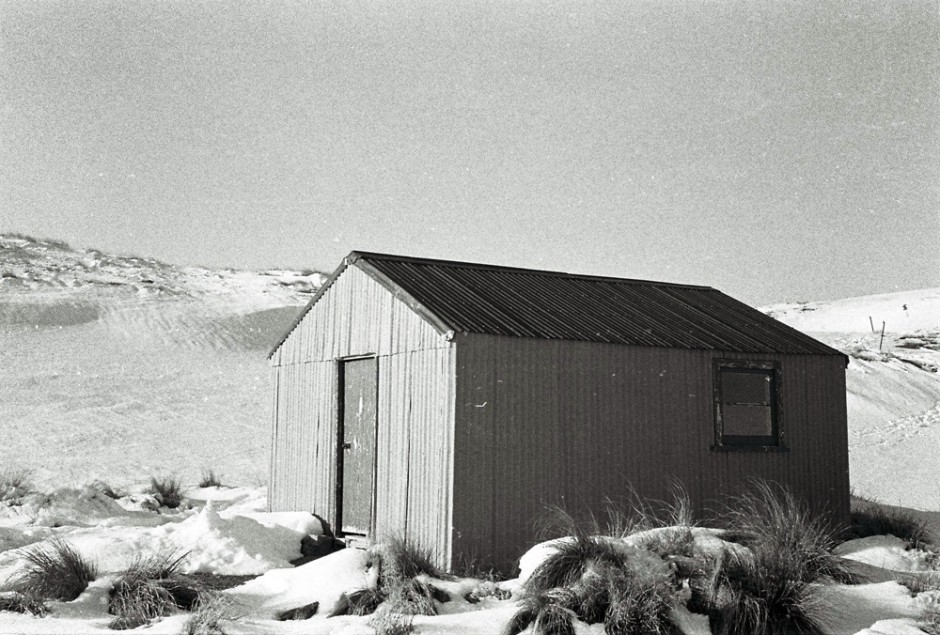

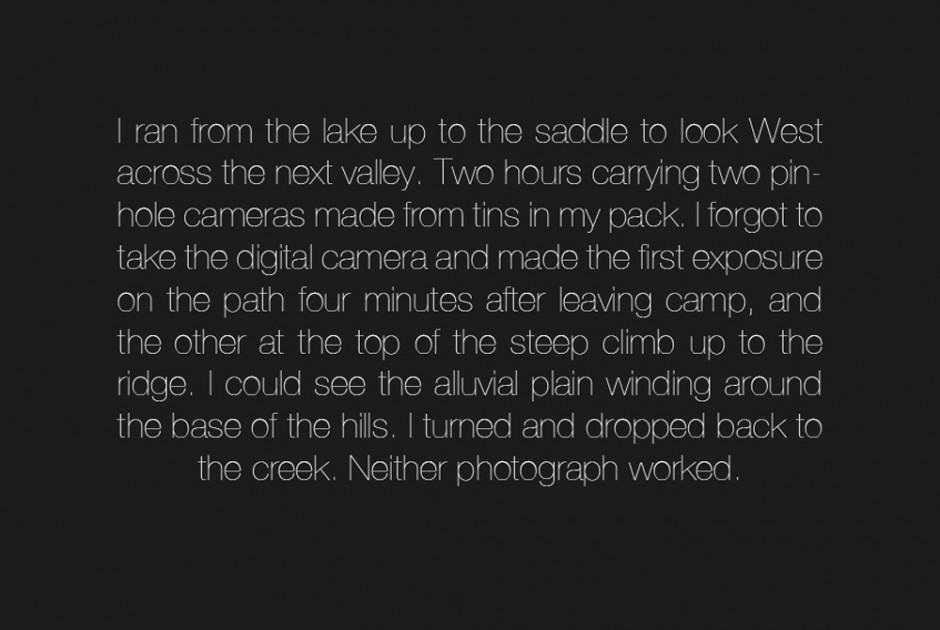

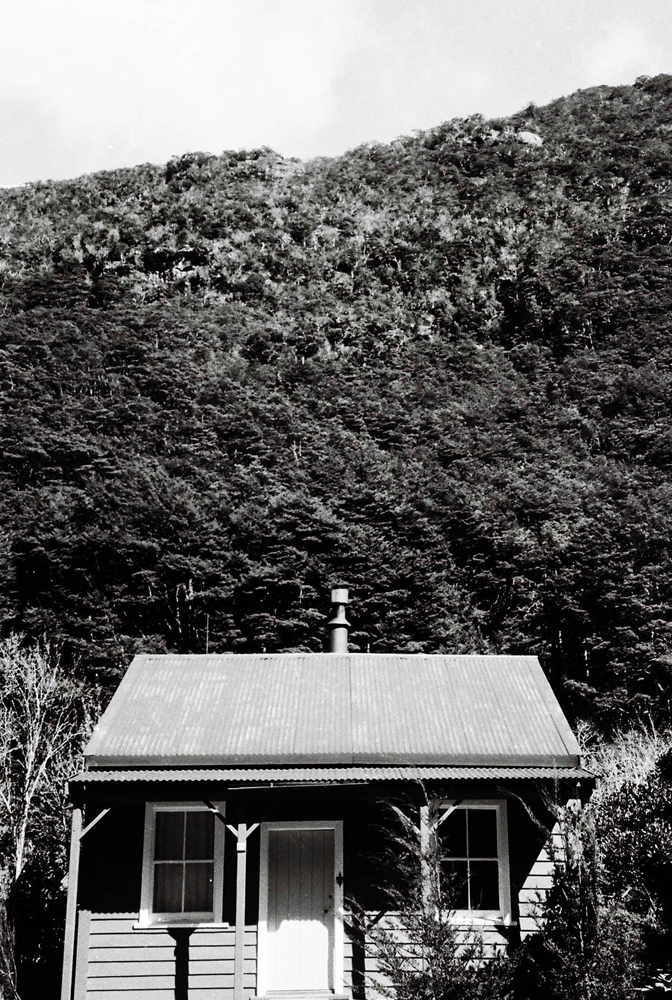

These tins became the bane of our lives: rolling out of the van every time we opened the door with a distinct clang, regardless of where they had been stored or the tranquillity of our location. Using these cameras forced me to really think about what I was photographing, as I could only make one exposure per tin each day, replacing the negative in the dark each evening. I carried five of them on a two-night walk (or tramp, as the Kiwis call it), diligently arranging them on the tables of backcountry huts for the nightly ritual. Only four of fifteen negatives came out usable.

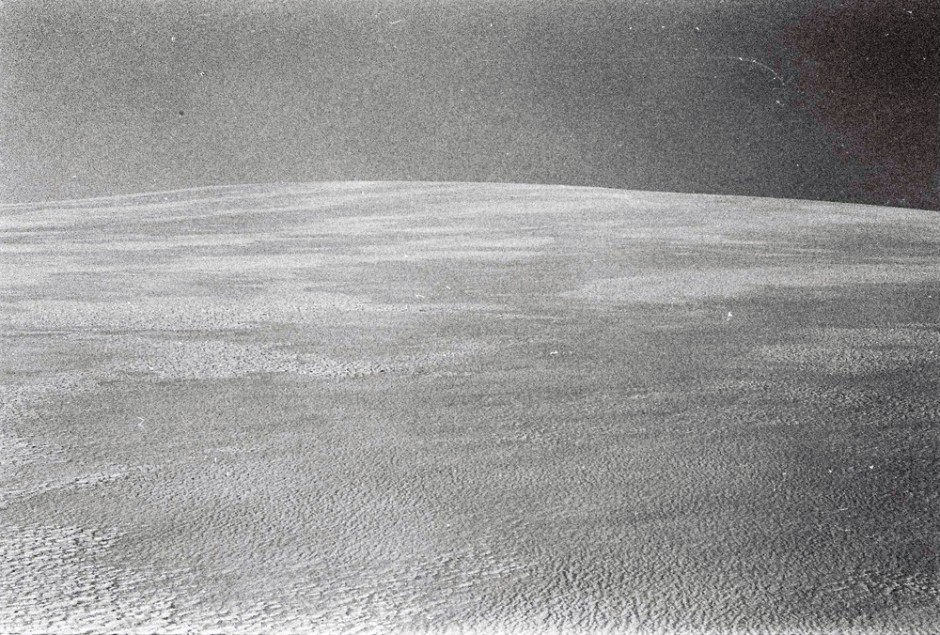

The joy of using these cameras though was the feeling of magic – the silence of light flooding through the pinhole as I peeled back the cardboard shutter was a beautiful antithesis to the click and wind of a film camera or the stuttering beeps of digital. Because the aperture which allows light into the tin is so small, and the paper not as sensitive as film, the negatives have to be exposed for a long time (around thirty seconds in sunlight) and this pushed me towards brief periods of meditation as I exposed them, sitting very still, counting the seconds and looking intently at the subject of the photograph. Sitting or kneeling even for half a minute makes you aware of so much more around you. The snow chills the knee which bears most of your body weight, you notice the movement of insects in the grass, the rain beats harder on your hood.

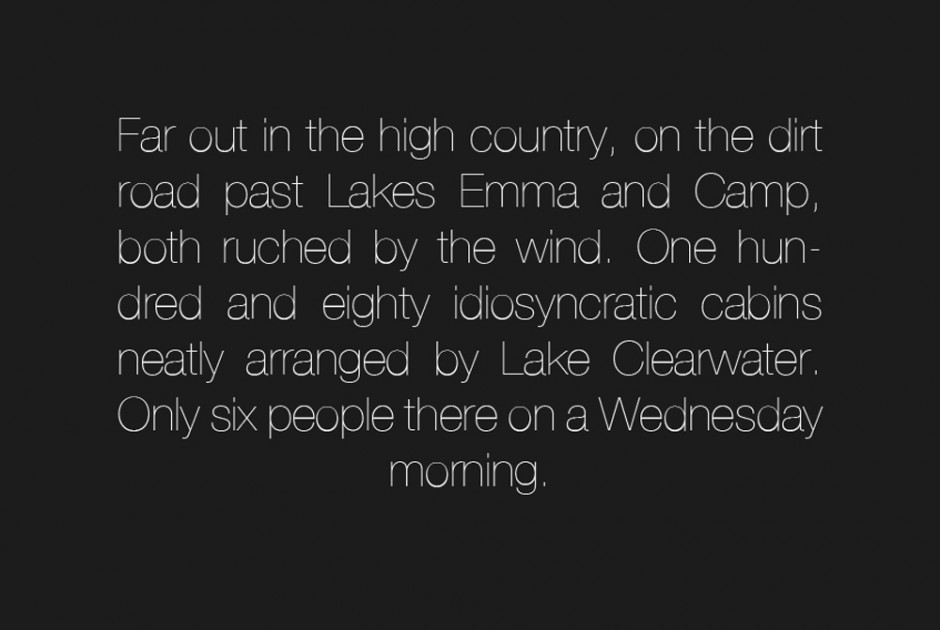

When shooting regular 35mm film in my small 1970s camera I tried to apply the same principles, and was reminded of the effort that used to go into every single photograph taken and disseminated. The small plastic canisters of black and white film accrued in a little wooden box in the van until we reached Arthur’s Pass, a high mountain settlement in the Southern Alps, where I developed several rolls of film in a camping shelter in the middle of the village – the first place in a few days with the necessary running water. The ribbons of negatives were strung up from the rafters, a delicate counterpoint to the tents and bicycling equipment that other campers were drying while waiting out the short-lived fall of late snow.

Over a couple of weeks, the films and unprocessed paper negatives built up, still withholding the images from view. We travelled further south up into the high farming country that forms the foothills of the Southern Alps, and it wasn’t until arriving in Christchurch, the South Island’s largest city, that I could begin to see the images of the last few weeks.

The physical alchemy of developing and fixing the paper negatives established a strong memory connection to our journey, and the timelines of thirty-six black and grey frames mapped out the changes in elevation and landscape we had moved through. This stage is immensely tactile, an aspect of photography which has definitely been lost through digitisation.

I wish I could hold the films up to the window for you, or you could feel the rough edges where I tore the paper and smell the chemicals: every photograph used to be made like this, touched by many hands before finding its way into print.

Intermission

Intermission

Intermission