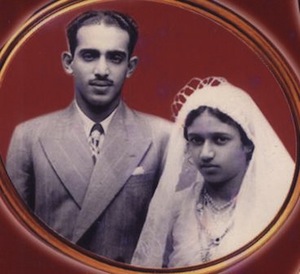

THE PHOTOGRAPH IS black and white. That is not surprising since it was taken 61 years ago. The edges are torn. The dark haired girl sits on a chair looking at the camera, unsmiling. Next to her, a tall man stands erect with his hands awkwardly clutching the back of the chair.

“I was 19 when I married your grandfather,” my grandmother tells me. “He came to see me; he asked me my name and what I had studied. Then, a few months later we were married.” Her marriage was arranged by her parents, as was my parents’ marriage, and as will be mine.

During my grandparents’ time, it was very orthodox. Girls were married in their late teens. There were not many women who pursued a career. From my perspective, the girls were duty-bound to be married. They did not even have a say in planning their wedding. The date, the venue, the menu, and, in some cases, the groom, were agreed upon by someone else. There was no courtship.

“There was no romance before the wedding,” reminisces my grandmother. “All that came after the wedding.”

There was hardly any chance to meet your fiance before the wedding. You could only wonder what he would be like, how your life together would be. Sometimes there was hardly any room to wonder, because in the short span from the time the marriage gets fixed to the actual day, there are a lot of things the bride-to-be has to learn. Traditional Kerala cuisine tops the list.

During my mother’s time, many things remained unchanged. She was enrolled in college for a Masters program when her great-aunt came with a proposal for a groom from another Syrian Christian family. The Syrian Christians of Kerala are a close-knit community with strong traditional values and an equally strong emphasis on family. To the Syrian Christians, a marriage is not simply the union of a girl and a boy, it is respected as the union of two families, two families from the same community with the same traditions and faith. Parents are wary of marrying their children into families they have not heard of.

When the proposal came, my grandparents started calling up people to inquire about my father’s family. There is a saying in Kerala that if you trace the family tree way back, you will find that everyone is related to everyone else. There is always someone you know, who was married into another family and who in turn knows someone else married into another family and so on. In our community, each family has a unique ‘family name’ along with the surname. It’s not really difficult to gather information about a certain person if you know their family name.

Family reputation, background, and financial standing matter a great deal. No one wants to marry their daughters into a family that cannot support them. At the same time, no one would want to marry their daughter into a family that is not reputable, no matter how wealthy they are.

During my mother’s time, courtship was not shunned, although it was not entirely encouraged. My mother met my father a couple of times. She still remembers my father rushing into the store where she was shopping for her wedding sari. They exchanged a few words under the watchful gaze of my grandmother. My father was too shy to come alone; he had dragged his younger brother along with him.

“He was the most handsome man I ever saw in my life, with thick dark hair,” my mother remembers. Looking at my father now with his near-bald head, the only proof that she is not lying is the photograph on her bedside table.

With the passage of time, the mindset has changed considerably. My parents have given me a relatively free hand. I have studied to my heart’s content. I have traveled solo to different continents and done other un-Syrian-Christian-like things. But when it comes to the matter of my marriage, I still fall under the reins of the Syrian Christian community. “Are you serious?!” my friend from Atlanta, whom I met in grad school, asks. “Yes,” I say. “My parents will find the groom.”

However the world progresses, I have learned that marrying their daughters off is one duty every Syrian Christian parent takes seriously. No one, not even a “rebel” like me, can change how that is done. Like my grandparents, my parents will find a suitable boy for me. They will call up people, who will know people, who in turn will know someone else.

“Aren’t you curious as to how he is going to be?” I don’t find his incredulity surprising. He was born and brought up in the West. He is bound to find it unsettling. Even I found it unsettling at first. But the truth is, even without knowing the person, I do have a general idea as to how he will be. After all, he is Syrian Christian; I already know how he was brought up.

All my life I have been a go-getter. This sitting around waiting for a suitable boy is new to me. What if the person does not like traveling? What if he does not read classics? What if he is not the adventurous kind? There are times when I consider an arranged marriage impractical in modern society. But I am a Syrian Christian. I have been brought up to respect my family and my traditions.

“Pray to St. Raphael,” advises my aunt. “He is the patron of happy meetings.”

“Say three Hail Marys every night,” advises another.

That’s the thing with us Syrian Christians: we are strong believers.