A small gathering at my apartment in Austin, TX quickly turned into a political discussion. We talked about the viability of a minor environmental protest that had seen a few picketers gather in front of the capitol building, waving at passing cars half-heartedly. Their signs were vague, I’d almost not seen them, and even as someone who stays attuned to environmental causes I was unsure what legislation they were referencing.

What American Activists Can Learn From Movements Around the World

My friend, a Parisian and world traveler and the only non-American present at the party, struggled to explain her confusion to us. “I just don’t get it,” she finally said. “What you do here, it’s not really protest. When we protest in France, we protest. We do not go to work. We do not go home. We are protesting—we are waiting for something to happen!”

Her boyfriend was quick to defend the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement, even though we all knew it was much deflated from what it had once been. Someone else mentioned Occupy—but, we had to admit, she had a point.

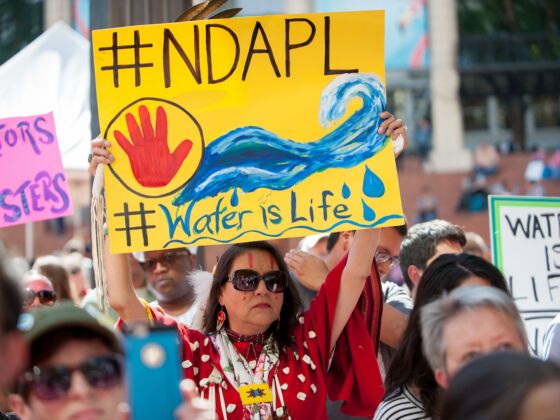

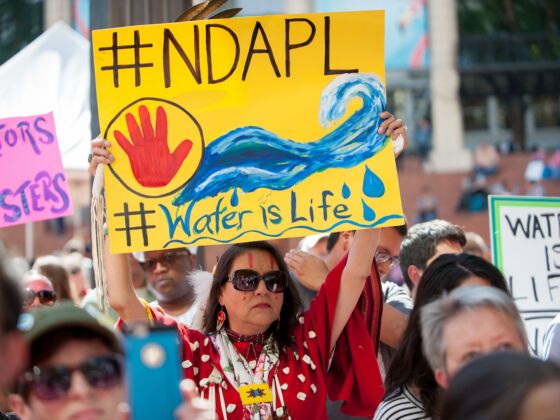

This conversation took place before the tenacity of the DAPL protesters had been proven, but still, the movement that happened in North Dakota last year was on a level that the U.S. hadn’t seen in years. We activists in the States could stand to learn a few things from protest movements around the world.

In France, effective protests do not have a stopping point.

In response to a proposed bill to scale back on long-held worker’s rights last year, the French labour movement and like-minded progressives protested in the streets of Paris for nearly five months, calling for a ‘nuit debout.’ The reality of this protest would see French demonstrators spending many nights making their stand, and then protesting even after Hollande pushed through the new measures without a parliamentary vote.

If this seems a futile exercise to our American way of thinking about political protests, it is paramount to remember that the Occupy Wall Street Movement in 2011-2012 frightened our government so badly that it required the involvement of the FBI and CIA. (And if that claim sounds like a dystopian novel to you, or your college roommate’s crack conspiracy theory—please follow the federal inquiries that are still being pursued in 2017.) What if U.S. protests were not confined to a one-time, hour-long event?

In Mexico, protesting doesn’t always mean picketing.

Often when I learn about a protest, the participants have planned to meet on a college campus and the meeting will require the purchase of innumerable Sharpies. While making signs and raising them in the streets is a heartfelt and important show of public sentiment, how much more could we accomplish if we didn’t limit our definition of protest?

For many Central American women, protest means bussing through Mexico in search of missing migrant workers who disappeared on their way to the U.S. It means fighting to raise consciousness amongst fellow citizens and apathetic government officials. Protesters in Mexico wear the photos of their sons and daughters around their necks as they trace their journey. In some cases, loved ones have been found while on this trail, but for countless more there is no real hope of finding the long lost ‘desaparecidos.’

In Brazil, even divided protest movements can bring forth change.

One of the most outrageous double-standards that the U.S. holds against its protest movements is that they ought to be fully unified on all matters. And yet I’m hard-pressed to name a single political movement in American history that had complete unity even during its earliest inception.

The complaint that’s frequently made against protest movements is that any infighting will preclude success. Yet in 2015, Brazilian protesters proved that this isn’t the case. The impeachment of former President Rousseff was called for by a series of protests with extremely disparate views. Activists (and it can be assumed citizens, as well) couldn’t even decide if she should be impeached, or just forced to resign during this unprecedented populist movement. They could agree, however, that the administration’s misdeeds were too great to be tolerated any longer. Protestors were even further divided by arguments over the prosecution of criminal charges, but they still irrefutably altered their nation’s history and took a huge leap forward in the name of ridding their government of corruption.

In Hong Kong, the police are not the faceless enemy.

During the Umbrella Revolution, pro-democracy demonstrators highlighted Beijing’s manipulation of elections in Hong Kong. The images of police officers in riot gear tear-gassing demonstrators caused tens of thousands of students to join the student protests in September of 2014. Meanwhile, in the U.S., where we’ve grown used to reports of student activists being pepper sprayed and tear gassed, most progressive protest movements view the cops as the unequivocal enemy.

As China hurried to suppress the protests in Hong Kong and images surfaced on the internet, reminiscent of Tiananmen, the attitude toward law enforcement was not what we in the States have come to expect. Psychologists reported the extreme emotional affects the protests had on police, reminding us that we are not fighting against the officers who live among us any more than we are fighting against our fellow citizens. We may fight to change their minds, but the ultimate goal of our movements could also be to garner sympathy and support from civil servants. Anti-police brutality shouldn’t mean anti-police.

In Australia, protest isn’t just for progressives.

Despite the international trend, passionate, articulate protests are not reserved for proponents of human rights and civil liberties. It is paramount to realize that a demonstration is just that: demonstrative of public sentiment. We cannot expect that a simple act of protest entitles the protest-sympathizers to a legislative response, as the Australians saw when two opposite protest movements clashed over national immigration policy. Unfortunately, these images of anti-Islam sentiment in Melbourne may become more familiar to Americans as white supremacist rallies in the wake of Donald Trump’s election.

If we expect our first amendment rights to be respected, we have to expect that freedom of speech will be protected for all people. We have to remember that protests are not their own exclusive entitlement. Progressives shouldn’t just demonstrate en masse, we should vote in national and local elections and have real conversations with the opposition, too. Counter-movements like the solidarity shown for Jewish culture in Whitefish, MT are proof that Americans can be successful at this.

In Bangladesh, there is never a promise of amnesty for protesters.

Not all protests accomplish their stated aims, of course. Even Americans recognize the high potential for failure and often take solace in ideas of consciousness raising and incremental change. Sometimes the efforts of protesters not only go unrewarded, they’re punished, as was the case in Bangladesh when hundreds of striking workers were fired out of hand.

The U.S.-supported Bangladeshi textile industry serves as a rebuke for those of us who protest without acknowledging the potential consequences of our voiced beliefs.

In Russia, if you don’t exercise the right to protest, those rights may be taken away.

The boycott of the Winter Olympics in 2014 showed that much can be accomplished when one nation’s marginalized protests are adopted by an international forum. But even though the pressure put on Putin led to the release of several of Russia’s notable political prisoners, unapologetic surveillance of activist groups and independent reporters shows that Russia is no more hospitable to freedom of expression than it was before the Olympics. The challenge now is to maintain the volume of the outcry.

Amongst the freed prisoners were two young members of Pussy Riot who had been jailed for a demonstration two years earlier. These two student artists turned activists now warn that the U.S. is headed the same way as Russia in this regard if we don’t take action while we’re able.

To say the very least, American protesters stand to learn a lot from a close study of social reform throughout the world and we have a lot to lose if we ignore these warnings. But even if we learn nothing else from world politics—let’s please agree to stop comforting ourselves with the dangerous delusion that social media can replace real action and sustained support for the movements that all too quickly disappear from our Facebook feed.