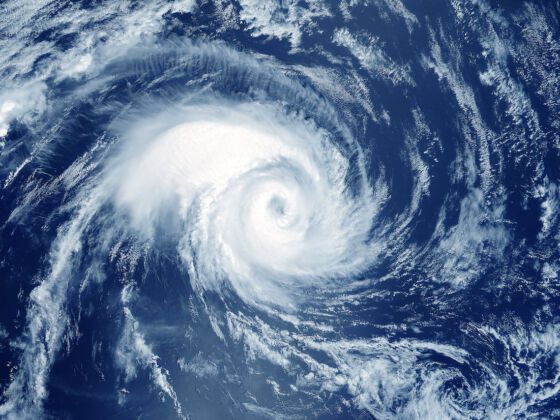

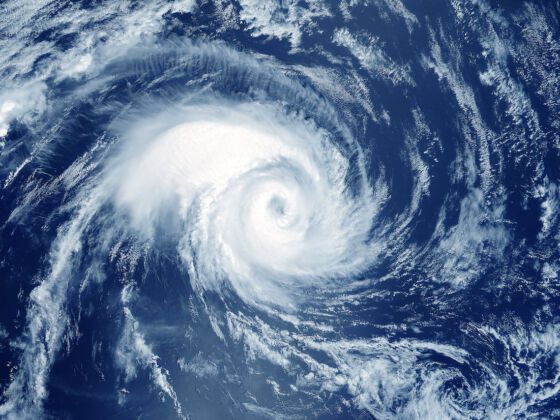

TRAVEL IS USUALLY thought of as a voluntary activity, involving suitcases packed with Hawaiian shirts, suntan lotion, and foreign language phrasebooks. But what about journeys taken when choice is not a factor, for example in the face of a natural disaster? Isn’t that also a kind of travel?

In the Face of Disaster, How and When Do We Travel?

Living in New York in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, I’ve been especially attuned to issues like these. I live uptown, where the lights stayed on. However, recently I took a walk below the 40th Street dividing line between the electricity haves and have-nots, and everywhere I saw people wearing drawn, weathered expressions and rolling suitcases, all headed north.

The recent storm has invited comparisons to a much worse monster, Katrina, which inspired a book of poetry that I place in the category of travel literature, if the boundaries of that genre may be stretched to include involuntary travel. I’m speaking here of Patricia Smith’s collection Blood Dazzler, published in 2008 and a finalist for the National Book Award.

Among the many complicated questions posed by this remarkable collection are: In the face of disaster, how and when do we travel? What do we take? And what happens when we return home?

Smith captures the dilemma of disaster travel in her poem “Man on the TV Say.” An award-winning performance poet, Smith channels the voice of a man who has trouble following what seems superficially to be a fairly clear message:

“Go. He say it simple…

… in that machine throat they got.”

But “Go” is actually not that simple of a direction when you know that anything you leave behind may be lost forever. Or when you don’t have the means or access to cars, gas, plane tickets, hotel reservations:

“…He act like we supposed

to wrap ourselves in picture frames, shadow boxes,

and bathroom rugs, then walk the freeway, racing

the water.”

And “Go” is an especially complicated direction when for whatever reason, travel is not something that you regularly do, or even think of doing. Not all of us have frequent flyer accounts. Not all of us have even ventured across state lines — and this can be true whether we’re six or sixty. As Smith’s narrator puts it:

“Even he got to know our favorite ritual is root

and that none of us done ever known a horizon.”

Smith is asking us to slow down here, to consider how and when we work up the nerve to go. When is the crucial moment at which we say, I cannot stay at home any longer? How do we determine that the risk of staying put outweighs the risk of leaving everything we own and know to go… where, exactly?

One fixture of disaster journalism is a focus on the people who fail to travel. Always implicit in such reporting is the question of why these people refuse to heed the evacuation warnings of the government and the media. Such failed travelers are usually portrayed as simple-minded, feeble, even selfish for potentially putting first responders in danger during post-storm rescue attempts. All this may or may not be true. But what these reports often fail to communicate, and what Smith’s poems remind us of, is that the decision to leave home is a heavy one to make.

In the aftermath of Sandy, my husband and I invited friends and family without power to stay at our place. My sister-in-law, who lives in Long Island, preferred to tough it out at home. Train service to the city was spotty. Once in New York, she wasn’t sure when she’d be able to return.

However, two friends from Jersey City, a couple, took us up on our offer. We made homemade pizza, laughed, drank Maker’s Mark, listened to music. At times, it was almost like a slumber party. Yet, as soon as they heard the news that the power had come back on where they lived, our guests’ faces lit up. They’d had enough of travel. They wanted to sleep in their own beds.