When I was studying art history in college, I frequently came across the name “Barnes Foundation” underneath the images in my textbooks. Unlike the other museums represented in those pages, the Barnes was not located in the heart of a metropolis like Paris or London or St. Petersburg, but in a town known as Lower Merion, Pennsylvania, a suburb northwest of Philadelphia.

The Destruction of Albert Barnes' Bold, Weird Dream

This out-of-the-way location was no accident. Albert C. Barnes, the wealthy and eccentric man who amassed a treasure trove of masterworks by artists like Matisse, Van Gogh, Picasso, Monet, and Renoir — now worth somewhere between $20 to $30 billion (but at this level, who’s counting?) — kept his distance from Philadelphia’s elite society after the first public exhibition of his work, in 1923, was savaged by the city’s art establishment.

Years later, tastes changed radically in Barnes’ favor, and the city of Philadelphia, particularly its Museum of Art, cast an envious eye on the Barnes Foundation, arguably the greatest collection of art that almost no one had seen. This was due not only to its location but also its stringent limitations on visitors. During Barnes’ lifetime, prospective visitors had to write letters requesting admission from the cantankerous millionaire, who denied the likes of poet T. S. Eliot and novelist James Michener. He was more interested in having art students than celebrities in his museum. After his death, visiting hours became more regular, but were limited, as were the numbers of people allowed to see the collection each day.

A few years ago, I realized my lifelong dream of visiting the Barnes Foundation, reserving my ticket ahead of time, renting a car, and driving out to Merion, with its stone and brick colonials and dense old-growth oak trees and shrubs that gave off an air of sedate, stately privilege.

The building itself was a solid gray fortress with Doric columns, surrounded by a formal garden and a smooth green lawn. Inside, the dark rooms were packed with masterpieces hung tightly together, salon-style, in heavy gold frames. There’s a Seurat! And right next to it, a Cezanne. Look there, hidden in that corner, a Van Gogh! And don’t forget that masterpiece by Matisse tucked in the stairwell, cast in shadows.

It was hard to focus on any one artwork in particular, which was exactly the intention of Barnes, for whom the beauty of a door hinge and a painting were the same thing. I felt the pressure to take in as much as possible, since it seemed unlikely that I’d be coming back any time soon. The experience was dizzying, overwhelming, and unforgettable.

In his will, Barnes explicitly stated that his collection could never be broken up and could never leave the building in Merion he’d constructed to house it. The trouble was, the foundation Barnes set up lacked the necessary funds to keep the museum in operation. Rather than create a board of prominent rich people who could easily raise the necessary cash to keep things going, Barnes left the management of the museum to a small local African-American college of moderate means, perhaps as yet one more “fuck you” to the Philadelphia elites he loathed so much. As the house began to need repairs, the money just wasn’t there.

The museum’s financial crisis provided an opportunity for the city of Philadelphia, aided by several prominent nonprofit organizations and the state of Pennsylvania, to go to court and get a judge to nullify the dictates of Barnes’ will, a story that is presented dramatically (and some say one-sidedly) in the documentary The Art of the Steal. And so, whether it was a Machiavellian plot or a rescue mission, the city of Philadelphia fulfilled its long-desired wish to move the collection downtown.

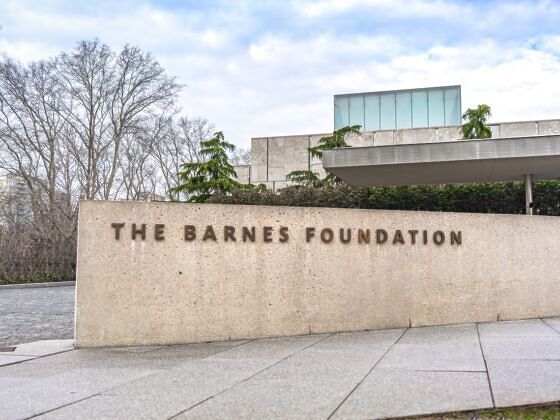

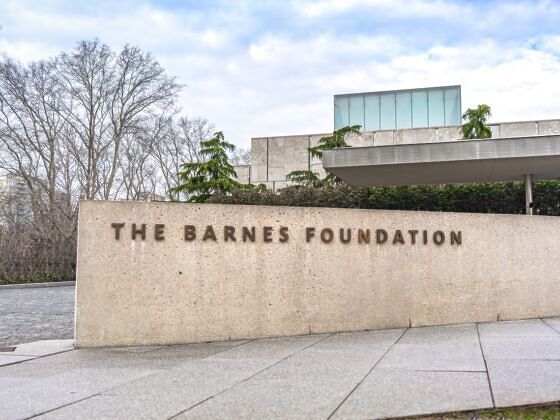

The Barnes Foundation is now marking the one-year anniversary of its move to Benjamin Franklin Parkway in downtown Philly, just up the road from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, whose front steps were made famous by the movie Rocky. Whereas before the museum could only accommodate a limited number of visitors, today it’s a must-see city highlight, where tickets are sold out nearly every day.

Recently I traveled to Philadelphia to see the new building, which from the outside is a series of handsome boxes, some of stone, and one, dramatically floating above the others, of glass. After entering the building, I passed through a long cavernous lobby which can be (and is) rented out for private functions. From there, I entered the galleries, where I was amazed to see the rooms of the old building replicated almost exactly, right down to the canvas walls and the arrangement of the pictures. In fact, several docents boasted that the paintings had been hung “within a sixteenth of an inch” of the original layout. The only difference was that the galleries admitted more light to make the paintings easier to see.

The building is tasteful, the paintings are well cared for, the visitors are flooding in. All should be well.

And yet, as good as this all sounds, I found my visit a bit sad. As beautifully and tastefully as this all was done, it was not what the man wanted done with his stuff. Maybe what he wanted was unreasonable and silly and vindictive and idealistic and weird. But isn’t that what made the Barnes Foundation so mythic, so interesting?

What happened to the Barnes is not unique to Philadelphia, or even the art world. There’s a tendency in our culture today to clean things up, present all choices in the same sparklingly clean modern boxes, without considering what gets lost in the translation. There was something nice — and yes, perhaps elitist, in the difficult variety of the past, and I fear the charm of that variety is in danger of disappearing.