My dad was a Vietnam vet, but he rarely spoke of it when I was growing up. I’d seen the scars on his hands where the shrapnel had ripped open his skin and earned him a Purple Heart. I knew he was a Marine trained to handle dogs that could sniff out booby traps, but not once did I hear him say “back in ‘Nam.” Nevertheless, his 1968–69 tour of duty, in all its insanity and absurdity, never seemed far from the surface of his consciousness.

Dispatches From Vietnam 40 Years After the War

It’s only now, a year after his death and my own trip to Vietnam, that I’m able to look for the parallels, if any, on how Asia shaped both of our lives — his in Vietnam as a young man and mine as a child in Indonesia.

Before my trip to Vietnam, I asked my stepmom, Becky, to whom he’d spoken more openly about his experiences there, where he’d been exactly in the country. His itinerary had been a circuit of the hotspots near the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone), where most of the fighting took place: Danang, Hue, Khe Sanh, Con Thien, Phu Bai, Dong Ha in Quang Trị Province, and the A Shau Valley. He also spent a few weeks in Saigon when he was wounded before doing a little R&R in Sydney, Australia, where the women were VERY friendly and had great tits. This last bit about the great tits was one of the stories he didn’t mind telling me over and over again when I was a little older.

Unlike my father’s, my itinerary for Vietnam would begin where he never ventured, in what was once the Communist-held north. My tour would follow a now well-worn tourist circuit: Hanoi, Sapa, and Halong Bay, and Hoi An and Hue on the central coast.

It was in Hanoi when I first began to feel the weight of war pressing down on me. At Hoa Lo Prison, or the “Hanoi Hilton” as the American pilots like John McCain had called it, the legacy of brutality initiated by the French became concrete. The stockades, solitary confinement cells, and torture chambers were chilling, but the pictures there, the pictures could not be unseen. The decapitated bodies of women, the burning flesh of children, the legless torsos of soldiers, the mass graves…it put a knot in my stomach. I felt queasy and had to step outside.

Even in the prison courtyard, the earthy smell of sticky rice drifted in from the streets of the Old Quarter. Here against the molding walls a memorial to the prisoners had been erected, and this is where the implications of what I’d seen struck me. To actually witness these kinds of horrors day in, day out for over a year, as my dad had, would’ve been psychologically devastating. They didn’t call it post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) back then. It was called the thousand-yard stare, and there was no doubt my dad had it. That anyone, let alone an entire country, could spring back from 20 years of such death and destruction (1955–1975) to become the next rising dragon of the East is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit.

My own resilience was wearing thin at this point, so at a trendy café overlooking Hoan Kiem Lake, the serene heart of Hanoi’s Old Quarter, I sipped an iced Vietnamese coffee to recharge with Hadeel, my Syrian wife and traveling companion on this trip.

After a few sips, she asked me about the Vietnam War. I told her the little I knew — that it had been as significant for America as it had been for Vietnam despite the discrepancies in body counts. The unprecedented TV coverage and freedom of movement for the press in the war zones allowed the world to see the reality of modern combat for the first time. Despite the propaganda then that said it was a fight against the evils of communism, anyone could see who the aggressor was. This spawned a cultural revolution in which every conventional idea and tradition was challenged. It divided America. Hadeel nodded thoughtfully as the city seethed and pulsated with vehicular and pedestrian life all around us.

It was then that I realized if I’d come here any earlier, as I was thinking of doing after I graduated from college in ’96, I’d have felt like a Hanoi Jane, a Communist sympathizer. Like any son, I’d tested my father, but coming to Vietnam back then, when it was just opening up, would’ve felt like betrayal to him and my country, even though I was fundamentally against the war. As it is, the now-still waters from that conflict run deeper and cut more decisively in the American psyche than they do on the shores of Hoan Kiem Lake.

Aside from Saigon and Danang, places I’d heard about from films like Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now, and from ’80s TV shows like China Beach and Tour of Duty, the names would never resonate with poignancy the way they must have with my father. I had no idea if walking down those same roads would help me deal with his death or give me a glimpse into what made him a man, but I felt as if it was the right thing to do for both of us, and at the very least, I had to try.

The first time I tried to imagine what it’d been like for my dad, no empathy, no imagination was required. It was purely experiential. I told Hadeel the story on the night train to Sapa, an old French hill station near the Chinese border.

In ’84, my dad, my stepmom, and I were in the Golden Triangle in Northern Thailand on our way back to the States from Jakarta, Indonesia. We’d hopped on a high-powered skiff on the Mekong River to get a peek into Communist Burma and opium-rich Laos. Just before the boat ride, I bought a conical hat like the local rice farmers wear. As we skimmed across the wide, brown waters of the Mekong, the tropical skies opened above us and released a monsoon shower. Everyone, except for me in my hat, was soaked within seconds. Over the roar of the rain, my dad turned to me and yelled, “Welcome to my world, son!”

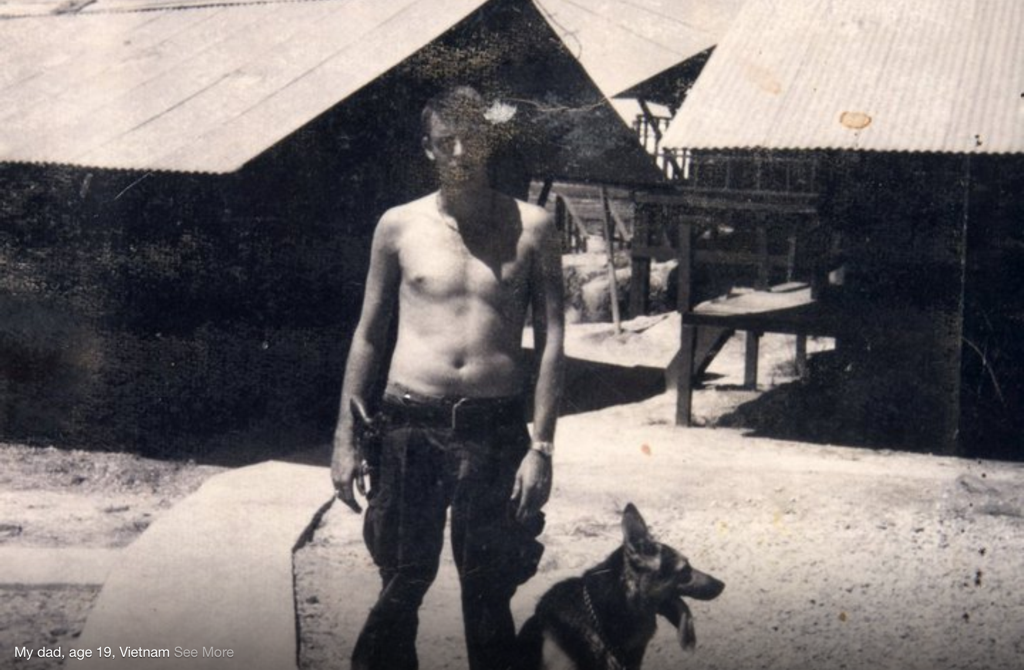

At the beginning of the rainy season, in September of ’68, my father landed in Danang on the central coast of Vietnam. Danny, as my grandparents called him, was just 19 years old at the time, the average age of a combat soldier in Vietnam.

Hun, as we affectionately called our Vietnamese guide on Halong Bay, was just a few years younger than me (about twice as old as my dad had been when he arrived in Vietnam). Being contemporaries of sorts, I felt obliged to joke around with him about our boat, a genuine Chinese junk, just not in the way advertised — more like a genuine piece of shit. He laughed, and as we cruised the emerald bays of dragon-back islands, he asked me why I’d come to Vietnam. I paused, and rather than tell him what I’d told the others, that friends had raved about how beautiful it is, I told him the truth. I told him my father was here, and I was looking for traces of him, of the boy he’d left behind. I don’t know if he understood, but he nodded, and when I asked, he told me his father had been in the war too.

In the war, my dad was a Marine Corps Sentry Dog Handler. He was given his dog, a German Shepherd named Gideon, and had two weeks to acclimate to him before going on his first assignment, recon with the 1st Marine Division. There, in the heat and humidity of tropical Vietnam, he sequestered himself in the cage with Gideon to get him to trust him, while he fed him during those first two weeks — just a boy and his dog on the brink of war.

It wasn’t until the brink of our departure from Vietnam that I reluctantly visited the Army Museum back in Hanoi — reluctant because I was afraid of what I’d find there.

Most striking of all was the post-modern sculpture made from all the planes shot down over Hanoi — from the French to the Americans, 20 years of aerial warfare in a single mass of twisted metal. Standing before it, I felt the weight of all those souls, both in the air and on the ground, come crashing down on me.

I reckoned my dad must have felt a similar gravitas upon his soul that needed unburdening from time to time after the war. Though he didn’t dwell on his service in Vietnam, he also didn’t mind telling my stepmom, Becky, stories of twists of fate, some of which didn’t happen and some of which actually did. Like the unfortunate deaths of Cabarubio and Triplett, dog handlers like my dad who both ended up KIA (killed in action) in July of ’69.

Triplett was a fellow Marine my father had just relieved of duty, and as he was leaving, his vehicle was blown up by a command-detonated mine right in front of my dad. Cabarubio had to step in for my father when he was laid up with malaria. He went into the bush alive, in my dad’s stead, and came back in a body bag, KIA by a booby trap.

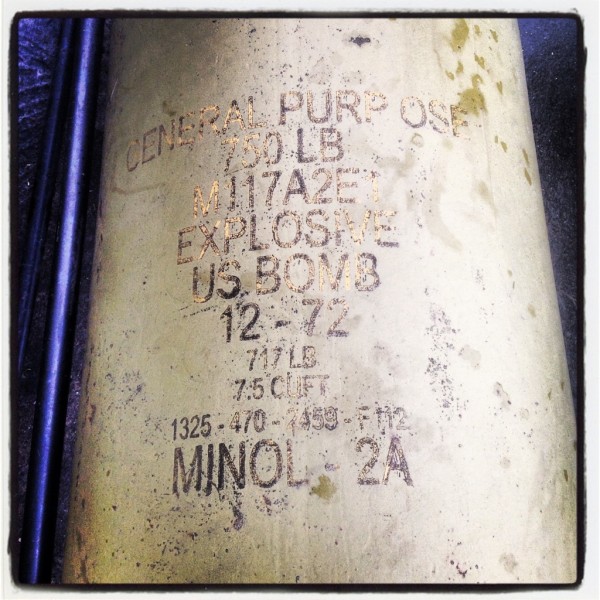

These were the same kinds of booby traps that my dad’s dog Gideon sniffed out when they would walk point. They were on display at the Army Museum in Hanoi, and I saw them all: bouncing betties, tripwires, balls of metal spikes, bamboo spears — each placard saying how many each trap had killed with dates and places.

Worst of all were the bamboo spikes with feces on the tips to insure infection. Once a soldier fell onto these spikes, the weight of his own body would drive the spears deeper into him, and he would often plead for his buddies to shoot him to stop the suffering. If he didn’t bleed out then, the infection got him later. These horrific thoughts went with me as Hadeel and I crossed the street, buzzing with motor scooters, to go watch the skateboarders in Lenin Park.

Under the shadow of a triumphant statue of Lenin, I reasoned that my father’s internal conflict with himself, survivor guilt battling it out with the instinct for self-preservation, must have erupted into full-scale psychological war inside his head.

I was able to get inside his head before his death in 2013, before the dementia had crippled his mind the way the MS had crippled his legs — a direct result of extensive exposure to Agent Orange. I’d mustered up the courage to ask him why in the hell he’d volunteered to go to war in the first place when everyone around him was doing all they could to dodge the draft.

He told me the story of his surfing buddy Kehoe Brown, and as I remembered it, I told it to Hadeel as we walked the tree-lined boulevards of the diplomatic quarter back to our hotel in the Old Quarter.

The spring break before my dad enlisted in the Marine Corps, he and Kehoe had met a couple girls from San Antonio who wanted to party and have some fun. So they all went out to Padre Island to drink some beer and have a midnight swim. When they’d paired off and my dad had gone to the dunes with his girl and Kehoe with his to the water, a riptide or the alcohol or something got him, and he ended up drowning. My dad found his body, and being the older one, he convinced himself it was his fault. Going to Vietnam would be his penance for Kehoe’s death.

Later that evening in Hanoi, we met up with Tony, a former colleague of mine, and his Vietnamese wife at Cong Café, a hip coffee joint on the shores of North Lake named in honor of the Viet Cong. While we were there discussing the theme of the café, the commercialization of the cultural and revolutionary aspects of the Vietnam War, it hit me.

Death, and the guilt my dad felt about his escape from it when others succumbed, had shaped the course of his life. A friend of my dad’s, who I used to work for and who made it out of Vietnam alive (being in the typing pool increases your chances of that), told me another story that lends credence to this notion. He told me that my father was in the Battle of Dewey Canyon II in A Shau Valley. Remembering the story then, I asked Tony if he’d heard of this battle. He nodded and said it was one of the bloodiest in the Vietnam War.

American forces were overrun and of the 196 Marines there, my father was one of 10 who made it out alive, hiding among his dead comrades so as not to be detected. When the choppers found them, they flew them back to “the Rockpile,” the fire support base, where he had two days’ rest while they rebuilt the company, and was then sent back out.

My stepmom, Becky, who’d been a sounding board for my dad over the course of their 30-year marriage, had never heard that story before. It could be chalked up to braggadocio, to booze, drugs, and wigged-out tough-guy Marines talking, but at this point, it doesn’t really matter if it’s true or not, just that it’s told. Like the story my father felt compelled to write (and which got him accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop) shortly after he returned home from the war, when the wounds were still raw and the details vivid.

While the wounds of my parents’ divorce — the death of my family as I knew it — aren’t raw anymore, nor the details particularly vivid, the guilt I feel for choosing to go with my father and stepmother to Indonesia rather than stay with my mom, brother, and sister in Texas has haunted me the way Kehoe Brown’s death did my dad.

Like my father who questioned why he’d escaped death when his friends had not, I too wondered why I should be the one to escape the wreckage of the past. Why should I be the one to break free from the weekly drama of a home plagued by drug abuse and not my brother and sister? How could we leave them behind? How could I not stay and help take care of my mom as my brother always had? Like my father, the shadow of regret and guilt soon eclipsed the carefree innocence of my youth.

Unable to deal with these adult feelings of longing, guilt, and remorse, I unconsciously turned them outwards into acts of violence on the streets of Jakarta. Like my dad in Vietnam when he was on patrol, I struck out into the Indonesian kampong surrounding our barbed-wire compound, cruising the back alleyways, rice paddies, and open fields among the shanties, looking for something to distract me from my thoughts.

That something was usually trouble, and I often found it. One time I was riding my bike on a shady side street near our villa. Concrete walls topped with broken glass and barbed wire divided Jalan Kechapi — gated opulence on one side and crushing poverty on the other. Sprawling bougainvillea, sprouting bursts of color from within the compound walls, spilled over into the street, while trenches, nothing more than open sewers, lined both sides of the lane, buttressing the walls and adding to the siege aesthetic.

As I was pedaling though this gauntlet, a few local boys rounded a corner on their bikes and descended on me at full speed. I was suddenly surrounded, and just inches away, they taunted me in Bahasa, acting as if they were going to ram me with their bikes.

Scared, I lost control and fell to the ground, scraping the skin from my knee and palm of my hand. The kids laughed and rode off. Infuriated, I ran and pushed the next Indonesian boy who rode by on his bike as hard as I could. He flew off his bicycle, bounced on the street, and rolled into the open sewer. After the sound of movement stopped, I heard him moan. I looked down at my bike. The front wheel and handlebars were out of alignment. Blood was dripping from my hand and knee.

Then I heard a roar — a roar of screaming village kids, brandishing machetes and sticks and throwing rocks, headed right towards me.

I clutched the wheel of my bike between my bloody knees and grabbed the handlebars to realign them, the roar of the mob louder now. As stones whizzed by my head, I mounted my 10-speed and started pedaling as fast as I could towards a main thoroughfare. Without looking, I careened into traffic and almost ran head on into a fast approaching truck. Daunted by the vehicular onslaught, and at the edge of their ‘village,’ the mob held back as I weaved my way through oncoming traffic to escape.

As we slurped down a steaming bowl of pho along the quayside in Hoi An, paper candle lanterns flickering by in the black water of night, Hadeel shook her head in disbelief. It wasn’t something I was proud of, but there was a reason I’d remembered it here in this ancient trading port. We were close to Danang and Hue where stories similar, but most assuredly more tragic, had unfolded for my father.

As Hadeel and I walked through the Hoi An night market after dinner, a kaleidoscope of primary colors and handcrafted treasures, my thoughts traveled back to the summer of ’84 when we flew back to Texas for a visit after a year in Indonesia.

The jubilant homecoming we were given by Becky’s family at the airport in Corpus was day and night from what my father experienced when he returned from Vietnam. There was no hero’s welcome waiting for him. No ticker-tape parade. During his one year, two months, and eight days of deployment, his first wife Sharon had shacked up with someone else, and my dad didn’t find out till he got back.

Heartbroken and confused, he signed up for another tour of duty in Vietnam but recanted the night before deployment when he met some girls from Malibu and dropped acid. He went AWOL but turned himself in after a week’s worth of soul searching. They gave him shock treatment and an honorable discharge with a monthly disability check for life to help ease his transition back into civilian life.

Flashbacks of the war haunted him at home, and sometimes he lashed out — still at war with himself. My future mother, with a child of her own already, saw the torment in my father, his longing for absolution as her own, and made him her life’s work. Of their union I was born — the sum of all their hopes and fears for the future, my dad’s first-born son as the war raged on for another four years.

In the last few years of my father’s life, it was as if Vietnam was all that was left. All subtlety was gone, only the primal remained. It was then that the stories began to come out, and the dementia, a sign he was in the advanced stages of multiple sclerosis brought about by exposure to Agent Orange, became painfully obvious.

At first they came haltingly, but once triggered the stories surfaced nearly incessantly — at inappropriate times and mostly disjointed and incomplete, just snippets of the maddening monotony of war punctuated by moments of unimaginably visceral horror. Through his frustration with his inability to express himself and be understood, we knew he realized his mind was being destroyed from within. To watch my father, a giant of a man both physically and mentally, descend slowly into the lonely oblivion of dementia was devastating. But it is, as Herodotus once wrote, that in peace sons bury their fathers, and in war fathers their sons.

The more I lingered there, the more my childhood in Jakarta seemed to bear similarities to my father’s passage into adulthood in Vietnam. The Asian setting, the coming-of-age scenario, the search for absolution, and the drama of violence played out for me, although on a much smaller scale, as they had for my dad. In drawing out these parallels between our lives, I’ve found a certain catharsis, a degree of understanding, and the acceptance of the past, indelibly shaped by our formative years in Southeast Asia.