I have to confess that until recently I had certain assumptions about place names: there were the “authentic” ones, meaning they were attached back in the day to an event or person. For instance Houston is named for Sam Houston, the Texas army general around at its founding. In a lesser category, I judged, were “commemorative” names, those that reach back into the past to borrow the sheen of history. Your Gettysburg Malls, etc.

The Failed Socialist Utopian Dream That Helped Make Dallas a Major City

But sometimes commemorative place-names do the opposite of borrowing: they use their symbolic power to keep alive otherwise obscure parts of history. Reunion Tower is such a place in my hometown, Dallas.

Its name derives from La Réunion, a colony of European socialists who settled across the river from Dallas — then a shabby little frontier village — in the 1850s. The colony did not last long, and many of its members tried to put the experience behind them.

La Réunion has fascinated a subset of folks in Dallas from the time it happened. But it also became more and more obscure as time passed.

Until John Scovell found it.

Scovell is CEO and President of Woodbine Development Corporation, which built Reunion Tower and the shiny Hyatt Regency hotel next to it. It is fair to say that Scovell is a player in Dallas. He’s a powerful man who’s quite involved in civic life here.

Back in 1972, Scovell was just a 26-year-old accountant when he was hired by Ray Hunt, heir to the H.L. Hunt oil fortune, who was starting a commercial development venture.

“I was president and janitor,” Scovell laughs about his job title back then. “I was all of the above.”

Hunt owned some land near Dallas’s downtown train station, called Union Station. The land was scruffy, down in a floodplain and hemmed in by railroad tracks and a big freeway. But Hunt and Scovell knew city leaders wanted to see this part of town developed with a hotel and civic arena. They helped set the whole venture in motion, but it needed a name. So John Scovell hired a marketing firm to find that name, which they presented at a meeting.

Their top name pick? “Esplanade.”

Scovell thought that was pretty boring — everything was called Esplanade in the 1970s.

“In a moment of weakness I raised my hand and said, ‘OK, you know it’s not fair just to say I don’t like the name, you have to come up with an alternative,’” he says. “So for some reason, I said I would take that assignment on.”

Scovell went hunting through Dallas history, looking for some inspiration. And that’s when he came across the story of La Réunion. Hunt’s planned development was nowhere near the site of this old colony, but “when I saw that I said, you know, that’s the name.”

So it became Reunion — minus the French “la.”

John Scovell, President and CEO of Woodbine Development Corporation in Dallas, shows off the original plan for the parcel of land he named after the La Réunion colony. Photo: Julia Barton/GlobalPost

Reunion incorporated the name of Union Station, and it had other good vibes: high school reunions, family reunions. It was a nod to history, but it also gave the place an exciting “destination” feeling.

Once completed in 1978, Reunion Tower and the buildings around it became instant landmarks. I celebrated my 10th birthday up in the revolving restaurant atop Reunion Tower. I attended my first rock concert in Reunion Arena. I didn’t know about the backstory of the name.

And yet, that story is really interesting. The La Réunion socialists were among those caught up a wave of political revolutions that had swept Europe, starting in Paris in 1848. If you think of Texas as one edge of the wave, the other shore is in Siberia. That’s how big it was.

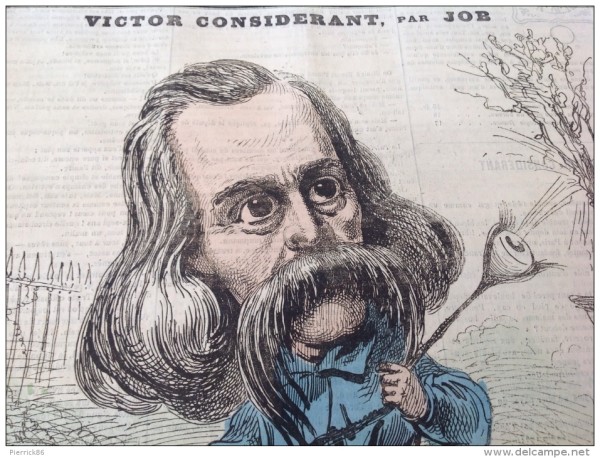

The influential people caught up in this wave include Marx and Wagner over in Germany, Victor Hugo in France, Fyodor Dostoyevsky in Russia. All shared a passionate hope for a new kind of society, whether in the form of nationalism or anarchy or socialism or democracy. All knew the work of one of the revolutionaries in Paris, the French socialist Victor Considerant, an advocate of direct democracy and critic of capitalism.The high didn’t last long — the revolutionary fervor dissolved in the face of authoritarian crackdowns.

“The disillusionment was enormous, [and] it was back to a situation that was worse than it was before these revolutions — the Spring of the People, as it was known,” says French historian Michel Cordillot, who’s studied what happened to these revolutionaries, many of whom were imprisoned or exiled from their home countries.

Photo: Public Domain

Victor Considerant was among those who fled France. In 1852, at the urging of his American fans, he came to the US and eventually traveled to Texas. Considerant loved it. He went back to Europe and published Au Texas — a rapturous account of the possibilities just waiting for European socialists on the frontier. He called for utopians of all types to come to Texas and show the world how it’s done: It would be a meeting place: la réunion.

Considerant was a very persuasive and trusted leader, and he offered hope to what were at the time despondent socialist dreamers. Within a few months, hundreds had pledged their life savings to help build a colony in Texas. They couldn’t fork over the money fast enough — much more than Considerant expected. So he sent his followers to buy some land outside Dallas, which he’d visited on his trip.

But the suffering began as soon as they got on boats. They had dreams, but not a very clear idea of what they were getting themselves into. And Considerant had overlooked a lot of trouble signs: The Texas heat. The lack of a navigable river. Slavery, and the violent politics around it. Land speculators and hucksters. And lots and lots of snakes.

To make matters worse, most of the European colonists had no farming skills. They were artisans and thinkers who mostly expected paradise, not frontier misery. They were no match for the harsh environment they’d unwittingly entered.

“It was a mess if you think about it, all those years,” says Chris Thevenet, whose great-great grandfather Michel Thevenet was part of La Réunion. We met in West Dallas at La Réunion Cemetery, one of the few physical remnants of the colony.

“I think Victor Considerant, he was a promoter, if you ask me,” Thevenet says, echoing the stories his grandparents passed down about the founder. “He promoted as much as he could. And when things failed, he disappeared.”

It’s true. As far as founding fathers go, Victor Considerant has to be one of the less inspiring. UC Santa Cruz professor emeritus Jonathan Beecher has written a great biography of Considerant, and he describes how miserable the man became at La Réunion. In the summer of 1856, two years after the colony started, Considerant ran away. That left the remaining colonists holding the bag: the venture was supposed to make a profit, and now they owed money to investors back in France.

“I see all these deed records from my family liquidating a lot of the land,” Thevenet says. “From what I’ve read, no one wanted to do it — once it was over, it was over, and Paris was a long way away.”

In developer John Scovell’s estimation, La Réunion was an idealistic, harmless experiment. Harmless enough that he’s built a whole shrine to the socialist venture in the lobby of his Hyatt Regency hotel, the shiny building attached to Reunion Tower.

There’s a mural-sized painting about the colony, framed photos, certificates in French and old maps. The moustachioed visage of Victor Considerant stares out at the buffet tables of the convention-goers. This hotel wall is the only place in Dallas that I know of where you can just stumble upon knowledge of La Réunion. The colony site itself was demolished a long time ago. It left few traces — but at the same time, it left a huge mark.

Many of the colonists did head back to Europe, including Considerant. But about 150 stayed, and historians credit Dallas’s early growth to the sudden arrival these people, among them architects, musicians, builders, bankers and editors. When the Civil War broke out, many of those immigrants tried hard not take a side — some even hid out in Mexico to avoid the Confederate draft. After the War, the Reconstruction government needed non-Confederates to run the town: there they were, these battered idealists.

There are streets and parks around Dallas named for some of the colonists who stayed, or who were at least remembered fondly. But not Victor Considerant. I guess it was hard for the surviving colonists to forgive the guy who fled, and who later wrote an angry letter calling La Réunion “a fatherless bastard,” according to Beecher. It takes a lot to restore one’s status as a founding father after a remark like that.

But La Réunion — maybe even Dallas as a major city — would never have happened without him, it’s the simple truth. At least he has Reunion Tower pointing like a giant finger to the obscure footnote of his presence in Dallas. Without Scovell’s decision to commemorate Considerant’s socialist venture, I doubt I would’ve known the sad yet fascinating story connecting my hometown to European history.

By Julia Barton, GlobalPost

This article is syndicated from GlobalPost.