The British Museum is immense. You could spend months trying to see and learn about the 80,000 objects displayed, but if you’re not a Londoner and can’t pop in daily during your lunch break to have a stroll in the galleries, you’ll need a plan to make your one-day visit worth it. To ensure you get to see the most significant pieces in the museum without getting a serious case of museum fatigue, we’ve asked British Museum expert Michael Raymond and Londoner and art expert Luci Stephens to give us some hot tips on how to crush this massive museum in just one day.

How to Crush the British Museum in One Day

Michael Raymond is an assistant curator at the Tate Modern. After studying history at the University of Sheffield, he moved to London to work as the project coordinator for the Asahi Shimbun Displays at the British Museum. For two years he worked in the exhibitions department, organizing temporary exhibitions with objects from across the collection, whether Japanese paintings or ancient cuneiform tablets.

Luci Stephens is the head of 20th-century art at Clarendon Fine Art, a contemporary art gallery located in Mayfair, London. Luci has a BA and MA in Art History from Kingston University and University College London and has worked at the National Gallery. Every chance she gets, she explores the nooks and crannies of the British Museum in search of a piece she has not yet seen.

- Before you go: the #1 piece of advice for visiting the British Museum

- The best times to visit

- Free tours and audio guides

- Where to start your visit

- Five must-see pieces and why they matter

- Most underrated pieces to check out

- What you can skip

- What you didn’t know

Before you go: the #1 piece of advice for visiting the British Museum

Photo: douglasmack/Shutterstock

Michael knows the museum like his back pocket and has not one but two pieces of advice he believes are essential for visitors to remember.

First, he urges you to use the back entrance on Montague Place to get in faster. This entrance is not as fancy as the Great Russell Street entrance with its stairs, colonnade, and pediment, but you can always go back around the building to snap a picture later. And don’t worry, no matter what entrance you choose, you’ll be able to access the Great Court and admire its magnificent glass ceiling.

Second, do yourself a favor and don’t bring large bags — you’ll have made a trip to the British Museum for nothing since they are not allowed inside. Leave your big items at the hotel and check out the galleries freely without being encumbered.

The best times to visit the British Museum

The museum opens at 10:00 AM daily and is usually busy from the get-go. A great option to avoid the crowds and get an early start is to book one of the special morning tours that start at 8:59 AM. The tours last one hour, don’t exceed 20 people, and cost $41.50 (£33). No matter what tours you choose, from a general introduction to the British Museum to a more specific presentation of Ancient Egypt artifacts, you’ll get a well-rounded, almost-private history lesson while everyone else lines up outside. Note that if you take a special morning tour, you need to use the main entrance on Great Russell Street.

If you want to see the collection freely, both Michael and Luci recommend Friday as the best day of the week to visit. Instead of closing at 5:00 PM, the museum stays open until 8:30 PM on Fridays, giving you the opportunity to see it in a different atmosphere. Friday is also the day when the museum hosts cool events like free demonstrations of the Japanese tea ceremony every second week, among others.

Although popular all year long, a visit in January or February will certainly be quieter than one in July or August.

Free tours and audio guides

Walking around to check out pieces at your own pace is a chill way to see the British Museum, but there are so many tours available that it’d be a shame to pass on trying one or two out — you’ll learn a ton, and it won’t cost you a penny.

The Eye-Opener tours are free, last 30 to 40 minutes, and take place daily, every 15 minutes from 11:15 AM to 3:15 PM. They are led by volunteers who will take you through the most popular parts of the museum to give you the lowdown on this particular part of the collection. There’s no need to book in advance — just be in the relevant gallery when it starts.

If you’ve followed our advice and decided to visit on a Friday, take one of the free, 20-minute Spotlight tours. Those tours focus on one topic (Death in Egypt, for example) or object (like the Rosetta Stone) to give visitors a brief but knowledge-packed talk.

If you’d rather remain independent during your museum visit, or if English is not your first language and you’re afraid you may not understand everything a guide would say on a tour, download the Audio App of the museum before your visit. The app provides expert commentary in five languages and allows you to access detailed descriptions of the most significant objects in the collection.

Where to start your visit

Photo: Matphotography/Shutterstock

If you’re not too far down the line to enter the museum in the morning, don’t waste any time and get yourself to rooms 62 and 63 on the third level to see the most famous objects in the museum: the Egyptian mummies. The museum has over 120 human mummies in its collection, as well as 300 animal mummies. While they are not all displayed, it’s very much worth hurrying up to those rooms to see the few that are there while the rest of the visitors are still on the main floor trying to figure out their way around.

Five must-see pieces and why they matter

Although we could easily include 10 more pieces on this list, if you want to get the highlights out of the way before you wander around freely to check out more niche objects, or take off to do something else entirely, Luci and Michael have selected five pieces that you cannot miss during your visit. (Luci recommends that you locate them on the museum map before your visit to save some precious time and beat the crowds.)

Note: All the pieces mentioned below appear in Neil MacGregor’s “A History of the World in 100 objects.” Neil MacGregor was the director of the British Museum between 2002 and 2015.

1. The Rosetta Stone

Photo: Jaroslav Moravcik/Shutterstock

Aside from the aforementioned Egyptian mummies, the Rosetta Stone is the most iconic object in the British Museum and the most-viewed item in any museum or gallery in the UK, according to our expert, Michael. There’s no right time to see the stone without the crowds unless you book a spot in the Introduction to Ancient Egypt special morning tour, which is greatly recommended.

The Rosetta Stone is a large grey stela with rough edges with the same text carved on it in Classical Greek, Demotic, and Hieroglyphics. Described as such, it does not sound like the most alluring object in the collection, but because it’s worked as the key to the understanding of the Ancient Egyptian civilization, it’s hugely important. Dating back to 196 BC, the stone’s inscriptions (which are the same decree in three different languages) led French Scholar François Champollion to crack the code of the Hieroglyphics language in the early 19th century. Thanks to his decipherment, the Hieroglyphics on other objects, in temples, on mummies, etc. were finally decoded, as were the mysterious rituals and traditions of a fascinating civilization.

Where to find it: In room four, in the Ancient Egyptian sculpture department right off the Great Court (on your right if you enter via Montague Place, on your left if you enter from Great Russell Street).

2. Parthenon sculptures, or Elgin Marbles

Photo: Giannis Papanikos/Shutterstock

The Parthenon sculptures, also known as the Elgin Marbles for Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire who brought some of the sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens back to England, are a beautiful display of marble reliefs created around 440 BC.

Originally, the pieces you’ll see in the British Museum were placed on the outside of the Parthenon, a temple dedicated to Athena the Virgin located on the Acropolis, and were colored in red, gold, and blue. The reliefs, meant to present passages of Greek mythology, are large and intricately carved to create life-like characters and scenes — the facial expressions, body shapes, and drapery details are nothing short of mind-blowing. Michael adds, “They look so soft, luscious, and realistic, it’s difficult to believe it was hand-carved from cold, hard marble.”

Having been taken from Greece in the early 1800s, there is a lot of debate as to whether the Parthenon sculptures belong to the British Museum or they should go back to Athens. Wherever you land on this issue, the sculptures should be at the top of your must-see list.

Where to find them: In room 18, on the ground floor, in the Ancient Greece and Rome department.

3. The Lewis Chessmen

Photo: British Museum/Facebook

If you’ve watched Ron and Harry play wizards chess and thought the pieces they used were “wicked,” you’re in for a treat. The real-life chess pieces that inspired those you can see in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone are on display at the British Museum.

Called the Lewis Chessmen because they were found on the island of Lewis in Scotland, the pieces date back from between 1150 to 1200 AD and were found in 1831. The pieces were made of walrus ivory and whales’ teeth in Norway, but not all of them are intricately shaped — the pawns, the least powerful pieces in a set, are just simple slabs, while the bishops, rooks, knights, kings, and queens are detailed and unique characters. It is believed that some pieces were painted red to distinguish the two sides. Eighty-two chessmen from several sets are at the British Museum and 11 are at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

In June 2019, a family in Edinburgh found a piece that they had purchased in 1964 for fewer than $10 at an auction in a drawer at their home. The rare, long-lost chessman, the missing piece of a precious set, was sold in July for nearly one million USD.

Where to find them: In room 40 in the Sir Paul and Lady Ruddock Gallery: Medieval Europe 1050–1500, on level three.

4. Hoa Hakananai’a (“Lost or Stolen Friend”) Moai statue

Photo: Jaroslav Moravcik/Shutterstock

For centuries, the people of Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island) built and erected colossal statues out of basalt on the coastline of their island to house the spirits of ancestors. Hoa Hakananai’a, built between 1000 and 1200 AD, is one of those monoliths, and it’s been on display in the British Museum since 1869. About seven feet tall, the statue is a simple yet extremely impressive carving. Visitors should make sure to check out the back of the statue, which bears symbols significant to the birdman religion, the cult that used to dominate the island.

Allegedly given to the officers of the British Ship Topaze by the people of Rapa Nui in the 19th century, “Hoa Hakananai’a” is today the center of much controversy. Spiritually important to the traditional inhabitants of Rapa Nui, they are now imploring the British government for its return.

Where to find it: In room 24 in the Africa, Oceania, and the Americas department on the ground floor. Straight ahead if you enter via Montague Place, straight on and just beyond the Great Court if you enter from Great Russell Street.

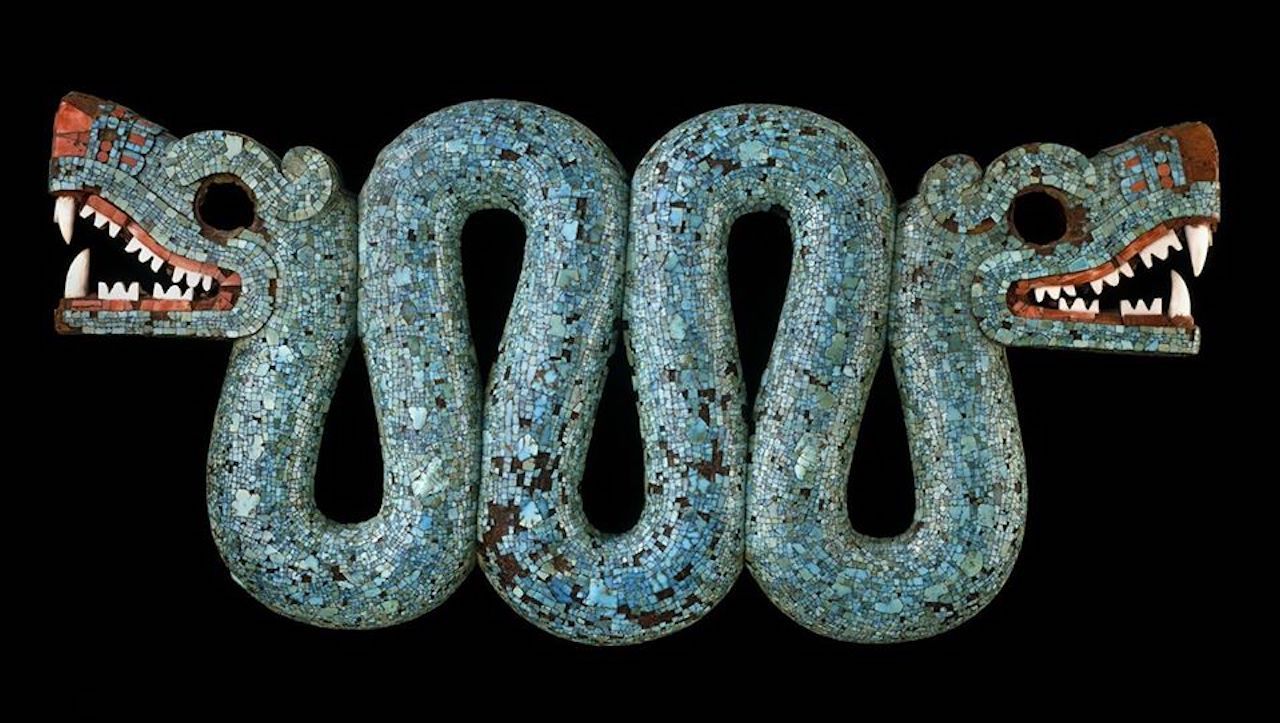

5. The double-headed serpent

Photo: British Museum/Facebook

Before the invasion of the Spaniards in the 16th century, Mexico was part of the huge Aztec Empire that stretched all the way from Texas to Guatemala. For the Aztecs, turquoise was a profoundly prized stone believed to used during ritual ceremonies and worn by Aztec rulers to show off their greatness. Serpents motifs were highly symbolic in Aztec culture; double-headed serpents were thought to be the bearers of bad omens. This intimidating double-headed serpent, carved from a single piece of cedar between 1400 and 1600 in Mexico, is inlaid with 2000 pieces of that very stone to create a gorgeous effect of shimmering scales. A piece of jewelry, the turquoise mosaic was meant to be worn on the chess of its owner, likely an Aztec ruler, like a brooch.

The Aztec empire was destroyed by the Spaniards soon after their arrival, but remains of the great civilization like this piece provide proof of the incredible talent of its people.

Where to find it: In room 27, on the ground floor, in the Americas department.

Most underrated pieces to check out

If you still have time and energy after you’ve had a good look at the five must-see pieces mentioned above, take your time to meander the galleries in search of the three following pieces recommended by Michael. They may not be well known, but they are certainly worth a few minutes of your time — or more.

1. The “Mermaid”

Photo: British Museum/Facebook

Although it looks like something that belongs to a cabinet of curiosity, this spooky-looking creature that looks very much like a mermaid is a piece of trickery. Said to have been caught in Japan in the 18th century and gifted to Prince Arthur of Connaught as the real deal, the mermaid is nothing more than a creepy piece of taxidermy of a monkey’s upper body and a fish’s tail. Still, it’s worth a stop since its display in Europe in the early 19th century likely convinced a lot of people that mythical creatures like mermaids in fact existed in faraway lands like Asia.

Where to find it: In room one in the Enlightenment department, right off the Great Court (on your left if you enter via Montague Place, on your right if you enter from Great Russell Street).

2. Map of Venice

Photo: British Museum/Facebook

Map lovers will have a field day with this detailed print of Venice. Nine-feet wide and three-feet high, this bird’s-eye view of the city was made well before drones existed — in 1500. According to Michael, “every roof, spire, street, and canal is mapped out in extraordinary detail. It’s as if the artist has memorized every detail from every street and building in the entire city.” There is a bench located right in front of the piece for visitors to take their time to scrutinize the map and admire the talent of the artist who created it, Jacopo de’ Barbari.

Where to find it: In room 90a, on level four, an area of the museum often neglected by visitors.

3. Ravi Shankar’s sitar

Because the world of music is so much more than guitars, pianos, and the oh-so-ubiquitous recorders, go check out the intricately decorated sitar that once belonged to world-renowned musician Ravi Shankar displayed at the British Museum since 2017. Michael reminds us, “Shankar was famous for teaching George Harrison to play the sitar and helping to introduce an Indian flavor to the Beatles music,” so whether you are a huge Beatles fan, a music fan, or just a lover of beautiful things, this large stringed instrument is an underestimated must-see.

Made of teak and two gourds, it is beautifully adorned with stained and inlaid bones and botanical carvings. The instrument was gifted to the museum by Ravi Shankar’s widow. To know what it sounds like, click the video above and watch Ravi Shankar’s daughter Anoushka Shankar, herself a musician, play it beautifully.

What you can skip

We said it for the Louvre, and we’ll say it again for the British Museum: Every single piece displayed is worth your attention as it is the result of extraordinary talent and historical significance. That said, visitors who are not experts in art history or rarely frequent museums may find themselves fatigued by certain sections.

For Michael, if you don’t have a clue what the difference is between Doric and Ionic, and don’t feel like practicing your Latin and Ancient Greek, it’s room 77 (“Greek and Roman architecture”) and room 78 (“Classical inscriptions”), both located in the basement, that you should skip. It’s a niche section of the museum that those uninterested in the topic can skip without guilt.

What you did not know

Not everyone can take a trip to London and spend a day leisurely walking the wonderful galleries of the British Museum. The British Museum understands this perfectly, and that’s why it has partnered with Google Streetview and Google Art and Culture — so anyone in the world with an internet connection can access its collection and see iconic objects. So, for an armchair cultural experience, just click and be transported by the beauty of art and history.