About our reporting

Suzie Dundas is the commissioning editor at Matador Network and a full-time travel journalist. Her work focuses on adventure travel, the outdoors, and unexpected destinations around the world, with a special focus on wildlife and ecology. She has written for Outside Magazine, BBC, Thrillist, AFAR, and Atlas Obscura, and is a contributing journalist at SFGate.com, where her work won a Lowell Thomas award for adventure travel journalism. She’s an author or contributing author on several travel guides, including 2022’s “Hiking Lake Tahoe.” You can read more of her work at SuzieDundas.com.

For this story, Suzie traveled to Wyoming and Montana in August of 2024. She spoke with more than a dozen experts and locals on the ground in both states, connected with numerous experts over phone and email, and met with biologists and tour guides within Yellowstone National Park. Matador Network paid all reporting and travel costs for this story.

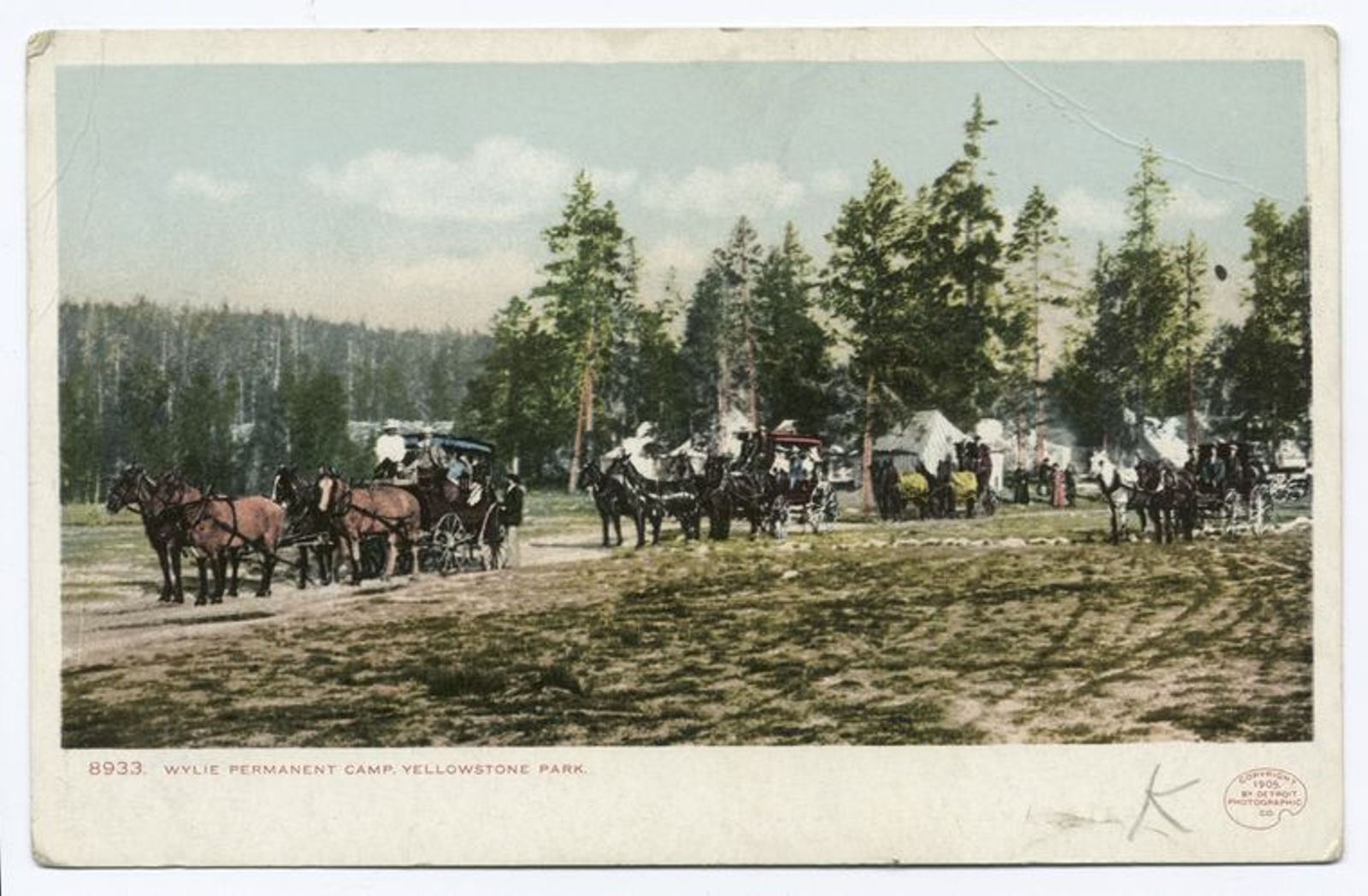

In 2024, the small outpost of Cinnabar, Montana, is a ghost town that has been abandoned since the early 1900s. But step back to 1890, and Cinnabar is the newly opened hub of the Northern Pacific Railroad and one of the busiest towns in Montana. The dusty, ramshackle town of saloons and supply stores is where visitors meet their stagecoach drivers from the Wylie Camping Company, ready to take them on a five-day tour of the newly formed Yellowstone National Park for $35.

An early photo of stagecoaches at a Wylie Camping Co. permanent camp in Yellowstone National Park, circa early 1900s. Photo: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection/New York Public Library/Public Domain

Guests ride in lumbering coaches, rattling over ruts and rocks and passing the well-heeled guests at the park’s luxurious National Hotel. They all gather to see the untamed beauty of “The Wonderland of the World.” With that comes a number of challenges: washed-out roads, flipped stagecoaches, and the threat of thieves.

And then there are the wolves.

Newspaper reports from the time describe a park “infested” with a growing population of wolves that are becoming a menace to tourists. While they may be special to the land’s Indigenous residents, most new settlers view them as a dangerous, chaotic remnant of the pre-America wilderness that citizens of the growing United States must tame. Even in 1890, extermination efforts are well underway. The park hires hunters to kill wolves, and government-backed bounties as high as $3 per wolf encourage further slaughter.

This was the prevailing attitude of travelers in the late 1800s and early 1900s, a sentiment that fueled what was later called the “longest, most relentless, and most ruthless persecution one species has ever waged against another.” The arrival of white settlers turned the gray wolf from a vital component of the natural world to public enemy number one. In less than 50 years, the howl of wolves that once echoed across the mountains and valleys of the mainland US was silenced, replaced by the roar of steam engines and the din of America’s ever-growing towns and cities.

Much has changed since. Cinnabar is long gone. The roads are safer, and millions of tourists a year drive along the Old Faithful Visitor Center’s raised, multi-lane highway exchange to stand in line for huckleberry-flavored ice cream, buy mass-produced national park t-shirts, and vie for one of nearly 2,000 seats surrounding the visitor center’s namesake geyser.

Large numbers of them also come to see the reintroduced wolves.

A morning double rainbow over Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley, Aug 2024. Photo: Suzie Dundas

On an August morning just after 5 AM, I’m standing in the park’s Lamar Valley, home of the country’s wolf-reintroduction efforts that started in the 1990s. With the road to my back and a cloud of darkness as far as the eye can see, it doesn’t take much imagination to envision how it must have felt to stand on the cusp of the unknown as a traveler with the Wylie Camping Company in the 19th century. When I hear the haunting howl of a wolf not too far away in the blackness, it hits me: despite all the park’s development, increased tourism access, and management of wilderness areas, it might as well still be 1890 in the Lamar Valley. The stealthy canine hunters are once again part of the ecosystem in parts of the American West, and their presence is once again influencing not just how humans interact with the landscape, but how Americans make — or lose — their fortunes.

Listen to wolves in Yellowstone National Park

The audio below was recorded in Yellowstone National Park. The park recently introduced a new analysis program that uses artificial intelligence to analyze thousands of hours of wildlife recordings. The goals are to better understand how wolves (and other species) use sounds to communicate, and to potentially “decode” certain types of vocalizations. All audio courtesy of Yellowstone National Park/the National Park Service.

Listen to: A pack of wolves howl during the evening while near an elk kill at Soda Butte.

Listen to: Wolves howling on Christmas morning just outside Officer’s Row, the historic employee housing within the park.

Listen to: A single wolf howling at a passing car within Yellowstone National Park.

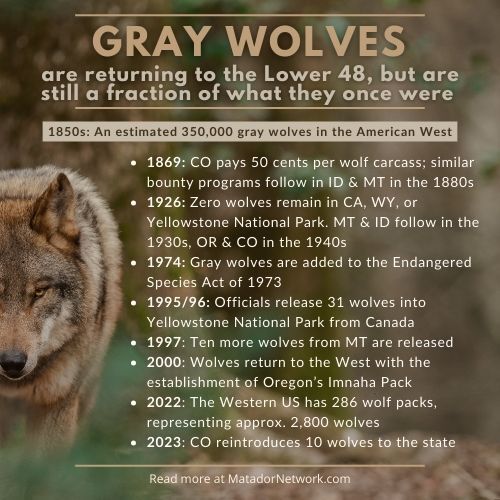

Wolves and westward expansion: from extermination to recovery

In 1872, Congress enacted the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act, establishing Yellowstone as America’s first national park. The legislation also put the park service under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior to safeguard the park’s natural resources “against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said park, and against their capture or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit.”

But by the early 1900s, Canis lupus (the gray wolf), seem to be exempt from protection against wanton destruction. They were seen as a detriment both to the park, and the nation as a whole.

“They are very destructive of game, and efforts will be made to kill them,” Yellowstone National Park superintendent Lloyd Brett wrote about wolves in the park’s 1914 annual report. (Coyotes, too, were vilified, hunted, and poisoned, though the populations never reached critically low numbers.) While a few early conservationists and park officials at the time advocated for more measured approaches to wolf management, they represented a minority view.

The 1918 annual report details government officials hiring hunters to kill the park’s wolves, and further reports detailed the number of wolves intentionally killed by the park service (28 in 1920 and eight in 1923, the last year wolves are mentioned as being in the park). Outside Yellowstone, Montana paid $80,000 in bounties on wolves between 1883 and 1918. Wyoming allocated $40,000, or about $1.46 million in today’s dollars when adjusted for inflation, to incentivize wolf hunting statewide.

By 1940, gray wolves were nearly extirpated from the US, save for a few lone wolves in Michigan’s northernmost reaches. Extermination programs succeeded largely due to minimal hunting regulations, financial incentives for killing wolves, rapid habitat destruction, and a widespread national sentiment that the only good wolf was a dead wolf. It was a time of wildlife policy that Yellowstone National Park biologist Dan Stahler describes to me as “heavy handed, with lots of cullings. A real predator eradication program.”

But by the 1970s and ’80s, public sentiment toward wildlife underwent a marked shift. People started to better understand the impact of losing an apex predator on the food web: elk overpopulation, unpredictable fluctuations in other species, vegetation loss due to overgrazing. Wolves were added to the Endangered Species Act list in 1974, mandating an eventual plan for their recovery, and early public comment periods showed public support for wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone by a margin of nine to one.

In 1991, Congress approved funds for wolf recovery efforts, and related environmental impact studies were completed in 1994. Immediately, Yellowstone began implementing its plan to reintroduce wolves, a move that Stahler describes as a necessary “regulating force.” While the decision was expected to stir controversy, particularly in the agriculture- and ranching-dominated regions of northwestern Wyoming, southwestern Montana, and Idaho (15 wolves were released in Idaho in 1995), it was not unfamiliar territory for the park.

“Yellowstone was at the heart of a lot of wildlife controversy ever since the Park Service was established…too few animals, too many animals,” Stahler says. “But restoring the wolf was really going to be important to restoring biodiversity.”

In January 1995, eight gray wolves from Canada were released in Yellowstone, followed by 31 more over the next two years. Now, approaching the 30th anniversary of the reintroduction effort, the descendants of the original wolves have dispersed across the American West, reaching as far as California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. The long-standing controversy around wolves has also spread, with ranchers and hunters advocating for relaxed regulations on culling to protect livestock, while conservationists and wildlife tourism businesses push for stronger protections and coexistence strategies.

The financial stakes of coexisting with wolves

The history of wolves in America could fill several books. In fact, it has; see American Wolf, Wolf Nation. While debates around the ethics, logistics, and successes of the country’s wolf reintroduction efforts are well-documented, less attention has been given to the economic impact, particularly the direct and peripheral benefits wolves bring to the tourism industry.

Choose any tourist town in wolf country, and you’ll find thriving guide businesses catering to travelers seeking the rare experience of seeing wolves in the wild. In areas around Jackson, Wyoming, and Gardiner and West Yellowstone in Montana, shutterbugs and wildlife photographers will shell out $700 or more a day to see the elusive creatures, often from such a distance that they’re only visible through high-end telescopic lenses. In Idaho and other parts of Montana, wolves are prized trophy animals for hunters, with Montana’s Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks alone generating nearly $5.4 million from wolf-hunting permits since 2009.

Whether wolves generate a profit directly for state governments is debatable. While Montana has earned millions from wolf-hunting permits, the state has also invested millions in wolf management over the years, with annual expenditures around $680,000. Wyoming spends approximately half that amount each year, funded by taxpayers, but brings in only about $45,000 per year in wolf-hunting permits.

“If you compare what we pay out in livestock damage versus what we make, the wolf program doesn’t make sense,” says Kenneth Mills, a wolf biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. “But that’s not the whole story.”

So what is the rest of the story? It’s the broader economic impact that wolves generate for private companies like photographers and tour guides, as well as the money that hunters and wildlife watchers alike spend on lodging, food, and travel in small towns and remote regions. It’s also the impact wolves have on livestock, ranching, and agriculture — three vital economic pillars in much of the American West.

How humans and predators coexist has changed since Yellowstone’s earliest days, but one thing remains the same: at the end of the day, it’s all about the money. And when it comes to wolf tourism, there’s a lot of money at stake. So I went to Wyoming and Montana to meet with wolf biologists and experts, tourism companies, town representatives, and park officials and guides to get the scoop directly on what the existence — or re-extermination — of wolves could mean for the people, communities, and economies.

Every wolf — and every rancher — matters in Wyoming

Wyoming Game and Fish biologist Ken Mills investigates an out-of-use wolf den in Bridger-Teton National Forest. Photo: Suzie Dundas

At 7 AM, in a roadside parking lot just south of Bondurant, Wyoming, I met Ken Mills, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s large carnivore specialist and lead biologist overseeing wolf management outside park boundaries. (The National Park Service handles wildlife management within Yellowstone and Grand Teton.) We headed down a rutted road in Bridger-Teton National Forest, passing through a closed gate before continuing on foot when the muddy, branch-covered road got too rough for vehicles. Our destination: a wolf den several miles into the forest, where we would retrieve footage from trail cameras and collect observations at the site, where six wolves were born earlier in the year.

Among states in which descendants of the reintroduced Yellowstone wolves have established packs — a list that also includes Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, California, and, at times, Colorado — Wyoming is unique. While Idaho and Montana maintain robust wolf populations, with roughly 1,300 and 1,100 wolves respectively, Wyoming’s numbers remain significantly smaller. West Coast wolf populations are also small, with just over 60 wolves in California and 178 in Oregon, but both states are still actively trying to grow their wolf populations.

It’s safe to say Wyoming is not.

Mills estimates that the non-park habitat in Wyoming can support around 160 wolves, explaining that this figure informs the state’s hunting quotas. Exceeding the carrying capacity can result in higher wolf mortality, both from natural causes such as increased competition, disease, and food scarcity, and from conflicts with humans. More wolves in populated areas leads to more interactions with livestock, which can prompt more lethal management responses. In the last few years, an average of about 30 wolves have been legally hunted each season.

With Wyoming’s wolf population significantly smaller than that of neighboring states, managing it requires a far more delicate balance. Even a few unexpected or illegal deaths can have serious repercussions, potentially leading to increased cub mortality or the dissolution of entire packs — of which the non-park parts of Wyoming have only 30. Mills knows exactly how many wolves are under his purview: 192, as of August 2024, and that’s an exact count, not an estimate. “We’re not running on some broad, computer-generated modeling efforts,” Mills told me. “It’s a census. We’ve counted those wolves. And the most we’ve ever missed was five.”

The fact that Wyoming’s numbers are so low, especially as it was home to the reintroduction efforts, may seem surprising. But according to Mills, much of the state outside of Yellowstone isn’t prime habitat. “Northwest Wyoming is by far the most suitable,” he said, citing its vast stretches of forested terrain and abundant prey. The rest of the state has dryer, more prairie-like conditions that are less conducive to sustaining large wolf populations.

But Mills is nothing if not pragmatic, and while we bushwhacked through the national forest, he explained a caveat about the rest of the state’s terrain. “It could be suitable,” he said. “But the human presence and presence of human activity is what makes it unsuitable.” Even if wolf packs could take hold in areas like Bighorn National Forest or farther east near Casper, they won’t, thanks to people. “Wolves are aversive to artificial scenarios,” Mills explained. “Wolves that learn to be cautious of artificial scenarios are less likely to be trapped or shot. And we already have wolves in all the suitable habitats that are left.”

The environment we hiked through is certainly suitable wolf habitat. It’s dotted with aspen trees and shrubby grasses, and we popped on and off of numerous game trails while making our way up the river canyon.

Is wildlife watching the West’s new Gold Rush?

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s wolf management efforts run on a budget of only about $350,000 per year, Mills said, and he does nearly all the monitoring, tracking, tagging, and field work himself. He feels it’s a labor of love, as well as a necessary expense. “We carry a financial burden because we think it’s necessary to serve the public.”

But while wolves are a red line item on Wyoming’s budget, for private companies, they’re a boon.

Joining us for our sojourn to the den is Taylor Phillips, owner and lead photographer of Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures. He estimates that around 60 photography and wildlife tour operators are now based in the Jackson area, up from just six when he started his business in 2008. His company offers around two dozen tours, most of them centered on wildlife. “People come to us because they want to experience the megafauna,” Phillips explained.

Phillips believes that Jackson residents tend to be more accepting of wolves than those in other parts of Wyoming. “Wolves are a controversial species,” he noted as we drove along the dusty national forest road. “But generally speaking, in Jackson, folks are very appreciative and welcoming of wolves.”

He credits that to the fact that Jackson doesn’t have as strong of an agricultural heritage as other towns in the state, though it does have a massive tourism economy. That creates fewer concerns about wolf-livestock interactions and a clearer line between the presence of wolves and an increase in tourism spending. It also means that monetary compensation for wolf kills isn’t a hot topic of conversation. In 2022, Wyoming paid $226,298 to ranchers to compensate for livestock killed by wolves. That’s less than the amount paid out for kills by grizzly bears ($418,000) or crop damage from white-tailed deer ($260,000).

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department estimates that there are just above 1,000 grizzlies throughout the state. Photo: Suzie Dundas

While agriculture isn’t a major industry in Jackson, wolves certainly are, especially for guides like Phillips. Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures offers multi-day winter wildlife trips that range from $5,200 to $7,600 per person. Phillips estimates that they spot wolves on about 90 percent of these trips, a success rate he attributes both to the healthy wolf population around Yellowstone and the expertise of his guides. Unlike the park’s omnipresent bison, wolves are elusive, driving travelers and wildlife photographers to seek out guides who know how to find them. Wolves aren’t something you see accidentally, he explained, and travelers booking tours to the Lamar Valley are almost exclusively looking for wolves.

“And think about the economic generator of that,” he added. “It’s in the millions. They’re eating at restaurants, they’re staying at hotels. And if we didn’t have the wildlife, we wouldn’t have the industry.”

Wolves are easiest to spot in winter, as they don’t hibernate and their dark coats contrast with the snow. Photo: Wyoming Office of Tourism

According to National Park Service data, most people visit the Grand Tetons region for the scenery and wildlife. Phillips has raised his photography excursion prices over time, carving his niche out in what he calls the “upper echelon” of tours. Charging more not only allows him to retain more talented guides and reach customers willing to invest in the experience, but also to put more time and effort toward wildlife conservation. He thinks a more collaborative, shared style of wildlife management between the agencies that manage the land immediately surrounding Yellowstone would benefit most nearby towns’ tourism economies.

“If there’s limited hunting around the parks, we could have what other towns have,” he said. “More consistent sightings.”

Phillips, who is both a hunter and wildlife guide, sees a disconnect between those who foot the bill for conservation efforts and those who see the benefit. He points out that most wildlife conservation funding comes from hunting and fishing licenses, firearm and ammunition sales, and conservation stamps. But it’s the tourism industry that benefits, in the form of more crowded hotels, busier restaurants, and a more active guiding and tour industry.

This imbalance prompted Phillips to establish Jackson-based WYldlife for Tomorrow a program of the Wyldlife Fund. Its goal is to encourage businesses that profit from wildlife tourism, such as hotels and guiding companies, to contribute to conservation programs across the state. The goal is to distribute the financial burden of conservation more equitably, and bring together everyone who shares an interest in maintaining healthy wildlife populations. WYldlife for Tomorrow has support from both sides of the conservation and hunting divide, focusing on common-sense initiatives that both groups can endorse.

“Wolves are delisted* and there are hunts that the state has authorized. A lot of people aren’t happy about that,” Phillips said. “But it’s important to consider the interests of the agricultural industry. That is part of Wyoming’s heritage, and needs to be considered.”

*Editor note: Gray wolves are still on the national endangered species list federally, with the exception of wolves in the northern Rocky Mountain range, including Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming.

It’s not ‘ranchers vs. wolves’ — but rancher livelihoods matter

The history of wolves and ranchers in the American West is one marked by conflict, rooted in the expansionist ethos of the 19th century and the need to eke out a living in the unforgiving Western frontier.

Ranching has been part of the culture of the west since the mi-1800s, well before states like Montana, Wyoming, or Colorado received statehood. Photo: Library of Congress/Arthur Rothstein/Public Domain

By the early 1800s, the livestock ranching industry had taken hold on the plains and mountain ranges of the West. The state-sponsored eradication campaigns and limitless hunting quotas were devastatingly effective, leading to the complete loss of wolves across the mainland US by the 1940s.

A century later, wolves are expanding across the US, and in some ways, the storyline is the same: ranchers who hate wolves on one side, conservationists and outdoor recreators who love wolves on the other. But according to the ranchers and agriculture professionals I spoke with, that’s an overly simplistic view. Ranchers, many of whom have a modern understanding of conservation and are themselves animal lovers, aren’t inherently anti-wolf. But they do worry about the impact on the state’s long-established rancher culture, as well as the influence of outsiders who don’t understand the challenges of raising livestock.

“We recognize that the presence of wolves has added to the positive experiences of visitors to Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks,” says Jim Magagna, executive vice president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA). “Those are appropriate places to maintain reasonable wolf populations.” The WSGA is an advocacy, lobbying, and professional development organization for Wyoming livestock and ranching families. It’s an industry that accounts for about $1.948 billion of Wyoming’s annual $47-ish billion GDP.

Magagna says the WYSGA works closely with state officials and legislators, as well as the Wyoming Game and Fish Department directly. While he acknowledges that most ranchers were against reintroduction, he says most of the organization’s concerns related to how the federal government managed wolves: “Wyoming ranchers have been supportive of the manner in which the state has managed wolves,” he says. WYSGA was also involved in developing regulations around the state’s “Predatory Animal Area,” an area in which ranchers aren’t compensated for any livestock killed by wolves. That was working fine, he says, but he’s critical of recent changes, many from outside Wyoming, that limit the methods by which ranchers can use lethal force against wolves to defend their livestock. It’s leading some ranchers in the state to support the idea of compensating rangers for any kills by wolves, even within the predatory area.

Cheyenne Frontier Days is the world’s largest outdoor rodeo and celebrates the state’s ongoing cowboy culture. Photo: Library of Congress/Carol M. Highsmith/Public Domain

“The ranching industry is foundational to Wyoming’s economy and culture,” he says. “And effective predator management is essential to maintaining this industry.”

Part of predator management includes wolf-kill compensation programs, in which rates are set by the market value of the livestock lost. The number changes, as with any other commodity. In Wyoming in October of 2024, a heifer (female cow yet to give birth) went for roughly $2.50 to $3.50 per pound, while a lamb in Colorado is valued at about $2.05 per pound. Most state’s wolf compensation programs pay ranchers not just for the direct value of the animal but also for indirect losses, usually by a multiplier of the animal’s value. In Wyoming, it’s up to seven times the market value.

But still, that’s not always sufficient.

“Losing livestock to any predator has long term effects — if a wolf kills a cow, you have lost the ‘factory’ that produces multiple calves in a lifetime,” says Charlene Camblin. “If the compensation isn’t adequate, then a rancher is losing ground with every loss.” Camblin and her husband co-own DC Land and Cattle Co., LLC, operating on a ranch her great-grandfather homesteaded in 1881. She agrees that the state does an excellent job of managing wolves but worries about the influence of people outside of Wyoming that can “buy influence” on federal policy without understanding the impact on the industry. “Too many people romanticize wildlife and attach human emotions to them,” she says. “They are animals who hunt and kill to feed themselves. A wolf knows that it has easy prey with livestock.”

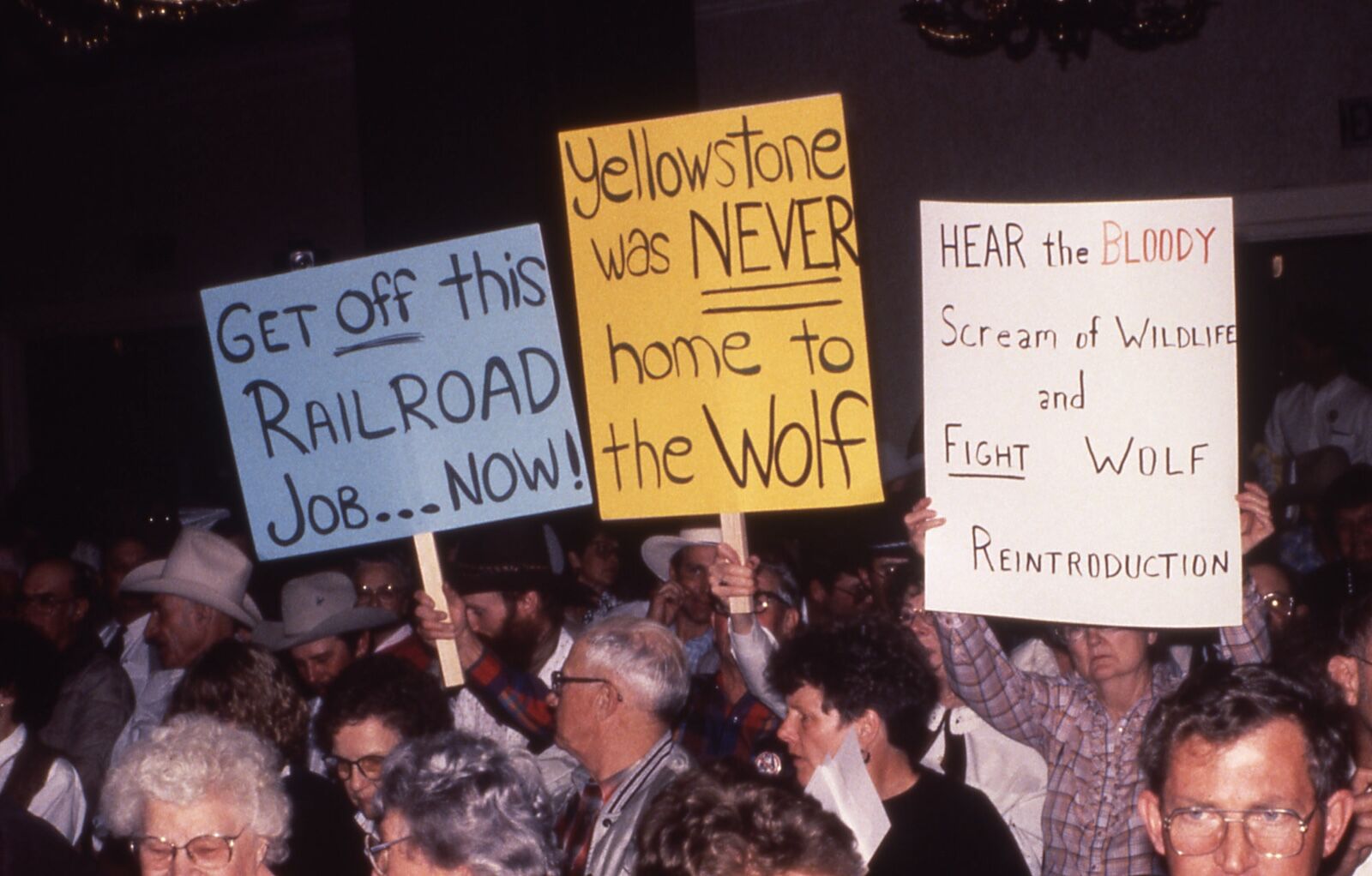

Managing public sentiment is as important as managing wolves

Protesters against wolf reintroduction at a hearing in Helena, Montana, 1996. Photo: NPS/Public domain

Like Phillips, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department also prioritizes efforts to shift public opinion toward an understanding of the benefits of wildlife conservation. On our hike to the wolf den, Mills explained that a key element of wolf management in Wyoming is navigating public sentiment, which tends to evolve slowly in the state. Mills has worked for the department since 2008, but recalls without hesitation how locals reacted to the return of wolves in 1995 and 1996.

“Oh, they didn’t want them,” he says.

Because wolf reintroduction was managed by the federal government, the wolves came regardless, moving beyond Yellowstone National Park boundaries in less than a year. Over the next 28 years, control of the wolf population shifted multiple times, with the state assuming management in 2008 after the federal government approved a plan deemed adequate to maintain a minimum population.

“When you have a species on the landscape and don’t have management authority over it, there are annoyances there,” explained Mills of why residents were frustrated by federal management of wolves in the state.

But later in 2008, that decision was blocked by a federal judge, and control went back to the federal government. It wasn’t until 2012 that that block was overturned, and wolf management returned to the state. That too was short lived, and it took until 2017 for a judge to side with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, agreeing that gray wolves could be delisted from the Endangered Species Act in Wyoming, sending management of the state’s wolves back to Wyoming on a permanent basis.

Wyoming’s wolf regulations are divided into three distinct zones (four, if you count the fully protected populations in Yellowstone National Park). This is largely to appease residents in areas where ranching and raising livestock are a large part of the economy.

A section of the state around the Grand Tetons is designated as a Trophy Game Management Area, in which wolf hunting is seasonal, regulated, and capped at a limited number of animals per year.

The largest section within the state by square miles is the Predatory Animal Area, where there are no caps and very little regulation on wolf killing. Anyone who takes a wolf in this zone is required to notify the government within 10 days, but in practice, there’s no way to regulate whether that happens or not. The vast majority of the state’s wolves live in either Yellowstone or the Trophy Game Management Area, not the Predatory Animal Area.

A very small section of the state switches between the Trophy Game Management Area and Predatory Animal Area designations in winter, allowing wolves to migrate between Wyoming and Idaho with lower chances of being killed. It was in this zone that Cody Roberts, the son of a Wyoming rancher, notoriously chased down a wolf with his snowmobile, bound its mouth, displayed the injured animal at a bar, and ultimately shot it later that night. The incident sparked national outrage and boycott calls on the state, particularly as the only legal infraction was his possession of a live wolf, for which he received a $250 fine.

A representative from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department acknowledged to me that many within the department were personally appalled by the incident, but that state law dictates penalties, leaving the department with limited recourse. “The Wyoming Game and Fish Department investigated and cited an individual who was found to be in possession of a live wolf. Under our jurisdictional authority and ability, the individual was cited for a misdemeanor violation of Wyoming Game and Fish Commission regulations, Chapter 10, Importation and Possession of Live Warm-Blooded Wildlife,” the department’s official statement noted.

Since animal cruelty laws in Wyoming, as in most states, don’t apply to wild animals, the department’s options were restricted. However, the public outcry following the incident led to the formation of the Treatment of Predatory Animals working group in the state legislature, tasked with reviewing “current law regarding predatory animals and the permissible methods of take for predatory animals.”

A balancing act: The impact of regulated hunting

In the early stages of wolf reintroduction, wolf hunting was permitted even when the population remained critically low — a decision Mills says was crucial for securing any level of public support. As we hiked, he explained that under the Endangered Species Act’s 10(j) rule, hunting was allowed for certain “experimental” populations, including the newly reintroduced wolves. This allows for looser regulations around their lethal and non-lethal treatment, and in Wyoming, it enabled landowners to kill wolves they believed posed a threat to their livestock. This is currently how Colorado’s wolves are classified, following a narrowly passed reintroduction vote in 2020.

“It’s this 10(j) part of the process that made wolf reintroduction possible in the West,” Mills told me. “Without the 10(j) rule, wolves could start killing livestock without recourse.” He shrugged. “What community that’s even remotely agricultural-based would agree to that? And you need communities to agree. If you don’t have local tolerance of a species, why even have it there?”

“Wolves aren’t going anywhere. People need to work with them.”

— Kenneth Mills, Wyoming Game and Fish Department

Mills thinks things have changed in the last 20 years in terms of social tolerance, but not necessarily due to attitude changes. “There’s some increased social tolerance, but also, it’s just reality,” he says. “Wolves aren’t going anywhere. People need to work with them.”

On that August Tuesday with Mills, after about 90 minutes of hiking, we reached the den, as well as two tree-mounted wildlife cameras. We crowded around the site, noticing signs of recent activity like wolf hair, wolf poop, and nearby bedding sites, likely used by the wolf pups once they were able to leave the safety of the den at around six weeks old.

We paused to review footage from the wildlife cameras, which have captured a range of animals, from black bears and red foxes to skunks. These cameras also record audio, providing a window into the wolves’ vocalizations, from aggressive calls to curious or even plaintive howls, as they navigate their typical four-to-six-year lives.

Above: Footage collected from a trail cam during the author’s hike, courtesy of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

Mills told me about the history of the pack in this area, describing an almost Shakespearean storyline of social upheavals, territorial struggles, and shifting alliances, where exiled wolves return to reclaim territory and fractured packs form and dissolve in an ongoing cycle of power and survival. This remote part of Bridger-Teton National Forest isn’t close to any dense human settlements, and the behavior captured on camera shows the wolves’ wild, natural behavior. While squatting, Mills flipped through the camera footage, looking at the various tails, paws, and antlers captured on the tiny screen. Then he stopped on one particularly interesting shot.

“Wow,” he said, looking closer at the screen. We scooted closer to see what he’s looking at — and realize it’s a wolf answering the call of nature.

“I know not everyone wants to see a wolf take a poop,” he said, “but it’s like, man, that’s pretty cool.”

While Mills clearly relishes his time in the field, his enthusiasm for the data-driven aspect of his work is just as evident. After our hike, we sat in the shade of an empty campground, and Mills walked me through a series of detailed graphs and charts based on his 15 years of data collection.

When it comes to predation, wolves killed 39 cows and five horses in 2022, potentially because the wolf population got too high and members needed to venture farther out for food. Wolves that develop a pattern of preying on livestock are typically killed (or “lethally removed”) as was the case with 15 animals in 2022 in response to those incidents — one of the lowest culling numbers in the state’s wolf management history. Mills believes the target population of 160 wolves strikes the right balance, minimizing lethal removals while keeping the population stable. He prefers to see a smaller number of wolves hunted legally, rather than seeing more wolves killed reactively in response to preying on livestock. But reaching that balance was a challenging process.

“It was difficult to watch everything change, watch the communities suffer, watch the wolves suffer. I didn’t want 113 wolves being killed for predation on livestock,” he said, referring to 2016, the most lethal year for wolves on record. “Who would want that?”

“In terms of data, [hunting] makes sense.

In terms of ethics, that’s another story.”

— Kenneth Mills, Wyoming Game and Fish Department

This is why Mills — and many protectors and defenders of wolves — aren’t against wolf hunting, as long as it’s properly managed. “We’ve shifted wolf fatality from lethal removal because of killing livestock to managed hunting,” he says. “So in terms of data, [hunting] makes sense. In terms of ethics, that’s another story.”

But data and science are what guide Mills’ work, and he’s realistic about finding a middle ground between conservation and hunting that most people can accept.

“We could value wolves over people, and say ‘forget how many livestock they kill,’ but there’s no compassion for the people in that scenario — or the livestock,” he said. “We have these local communities that live with wolves, and part of my goal is to make space for wolves: social space.”

A trip to ground zero for America’s wolf reintroduction

Sylvan Lake, within Yellowstone National Park. Photo: Suzie Dundas

After spending the day with Mills, I headed north, passing through Grand Teton National Park to enter Yellowstone, the heart of the country’s wolf reintroduction program. While the Wyoming Game and Fish Department serves the state’s 600,000 residents, Yellowstone can welcome up to 900,000 visitors per month during high season. Knowing that wildlife watching, and specifically wolf watching, is one of the park’s main draws, I was eager not only to gather insights firsthand, but also to see if I might catch a glimpse of one of the park’s renowned wolves.

As wolves are most active at dawn and dusk, I woke up bright and early on a midweek morning to meet a guide from Xanterra at the park’s far north Mammoth Hot Springs. Xanterra, one of the park’s official concessionaires, manages hotels, gift shops, and wildlife-watching tours across the park. “People come to Yellowstone for many reasons, and wildlife watching is one of the main attractions,” Leslie Quinn, Xanterra’s Interpretive Specialist at Yellowstone National Park lodges, tells me. Xanterra has run tours like “Wake up with Wildlife” and “Picture Perfect Photo Safari” for more than a decade, with morning and evening excursions routinely selling out. Among Xanterra tour guests, Quinn says it’s wolves and grizzlies that people are most keen to see.

“Only two ‘items’ [in the park] have large followings: wolves and geysers,” he says. “We speak of the ‘wolf watchers’ and the ‘geyser gazers,’ but have no nicknames for any other groups, as there just aren’t any [followings] with the size of those two.”

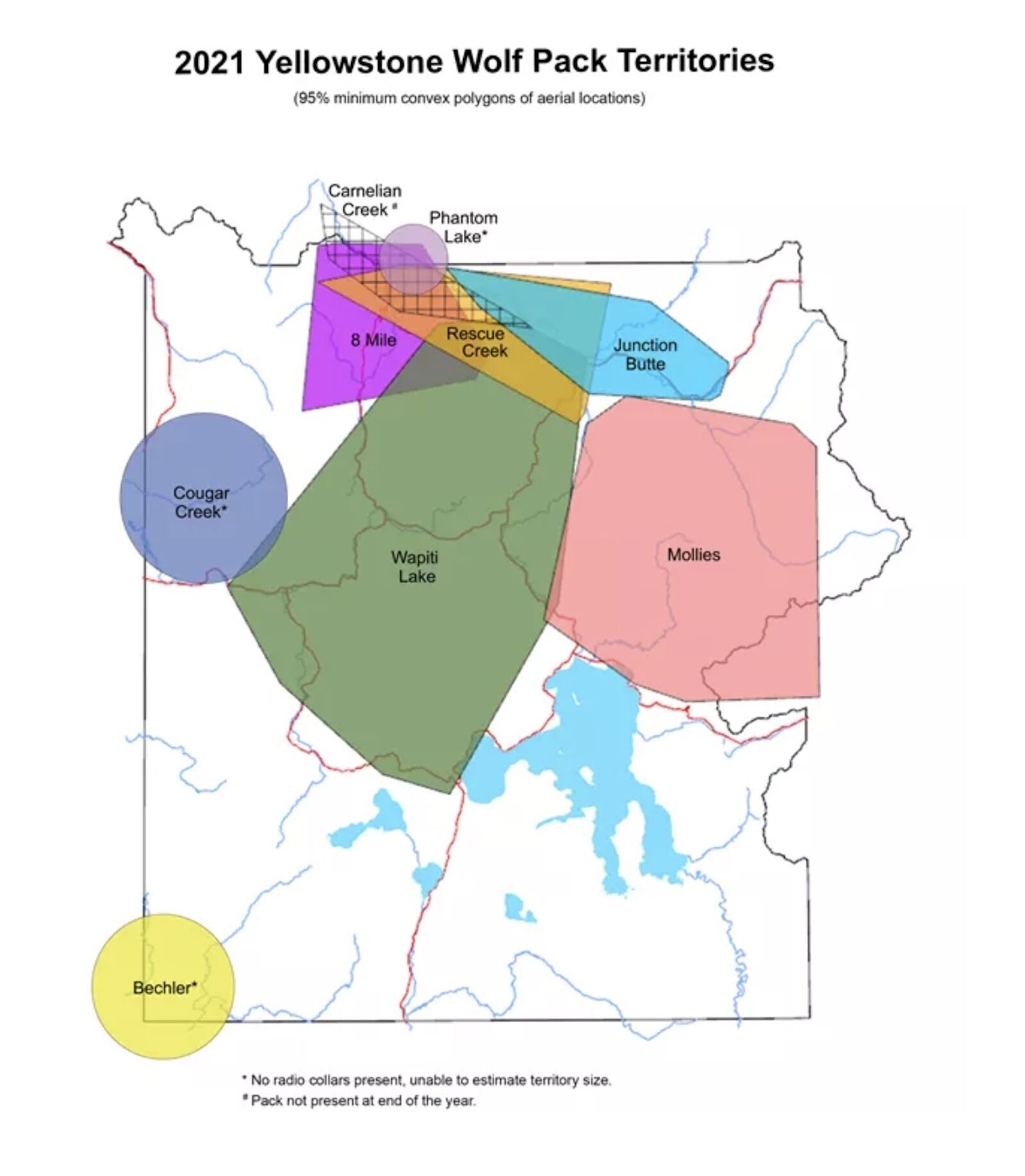

The next day in Yellowstone, I met with Dan Stahler, the park’s senior wildlife biologist and lead on the Yellowstone wolf, cougar, and elk projects. His team of just three year-round employees, along with a few seasonal summer hires, manages the approximately $1 million the park allocates to monitoring and researching wolves within its boundaries. Yellowstone is home to between 124 and 130 wolves in 11 packs, a number Stahler believes aligns with the park’s carrying capacity. An independent contractor hired by the park service estimated the park’s Canis lupus provide an economic value of $82 million per year, up from $35 million in 2005.

Gray wolves are an indigenous species that “took to Yellowstone really nicely” during the reintroduction, Stahler says. This is in spite of a 70-year absence in the Yellowstone food web, thanks to the park’s early eradication program for wolves and coyotes. But that eradication program did have a small silver lining: It was the start of a nearly 100-year-long period of study on the impacts of human interference, creating one of the longest-running predator-prey studies in the world. Since the late 1960s, Yellowstone has followed a policy of “natural regulation” for established species. It’s a philosophy Stahler describes as “letting nature take its course.”

Above: Wolves and a grizzly in the Lamar Valley, courtesy Yellowstone National Park/NPS

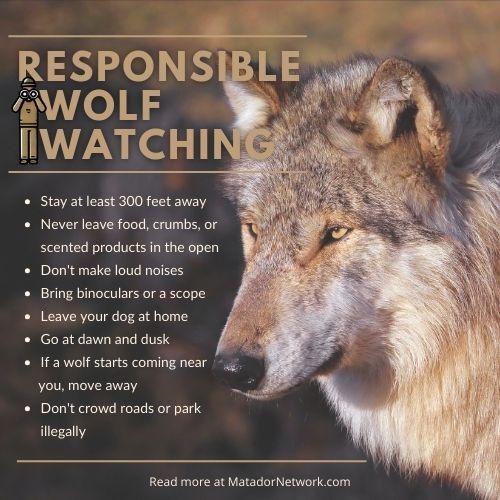

According to Stahler, the rare occasions when biologists intervene with wolves are driven more by human behavior than the animals themselves. “One of our biggest management actions is keeping wolves wild and safe from disturbances from visitors, and making sure wolves do not become habituated to people,” he says as we sit in a historic building that housed the Yellowstone army barracks before the National Park Service was founded.

Some visitors still try to feed wolves, he says, allowing the wolves to become too comfortable with people. When wolves begin to approach roads or hikers, the park takes measures to alter their behavior, from shouting and clapping to using deterrents like paintballs. It’s effective, he says, and “despite having over four million visitors a year, for the last decade or so, we have had wolves that largely act as wild wolves.” That means their behavior isn’t influenced by the presence of humans, helping to minimize the kind of human-animal conflicts that can result in individual animals being euthanized. In the last 30 years, Yellowstone has lethally removed only two wolves whose behavior threatened human safety.

Stahler notes that while the park collaborates closely with Montana and Wyoming, differing management policies can lead to tensions. Montana removed its statewide wolf-hunting quota during the 2022 hunting season, and it was the deadliest year on record for Yellowstone wolves. At least 25 wolves that crossed out of the park’s borders were killed. Following the most recent hunting season of 2023/2024, three park packs collapsed as a result of overhunting in Montana. In response, Yellowstone worked with Montana wildlife officials and other partners to tighten hunting regulations and shrink the hunting zones, aiming to prevent the kind of over-harvesting that can wipe out entire packs. In 2024, one such newly shrunk hunting zone near Gardiner reached its wolf-hunting quota of three on October 26, roughly five weeks after the start of hunting season. One wolf killed was wearing a national park tracking collar, indicating it had crossed out of Yellowstone’s boundaries.

Like its wolves, Yellowstone’s influence extends beyond the park borders: its wolves are recognized as vital not only to the park, but also to the region’s economy. “It’s a huge economic engine — people that not only want to see wildlife, but wolves, specifically,” he says. “And we know that a place like Yellowstone that supports a healthy wildlife system is really important to a lot of those values.”

“It’s challenging. Are we loving our parks to death?”

— Dan Stahler, Yellowstone National Park

The park’s healthy ecosystems are such a draw in the park that addressing overtourism has become part of every department’s charge. “In 2016, there was a National Park Service campaign called ‘Find Your Park,’” Stahler shared. “But then after the place got so bombarded, it was like, ‘um, well, maybe find another park.’ It’s challenging. Are we loving our parks to death?”

He says the answer is mostly education via everything from public lectures and signage to law enforcement. He acknowledges that messaging about wolves is particularly challenging both due to the strong public interest in viewing them, and the centuries of misinformation around them as a species.

“Wolves in particular have this tremendous grip on the human psyche, right?” he posited. “And it goes back, way back in our evolutionary history. You know, our ancestors competed with wolves for food. They sometimes attacked and killed each other.”

Yellowstone wolf pack territories, 2021. Photo: National Park Service

Stahler views places like Yellowstone — where reintroduction advocates thought most people would never see the elusive animals, but now is arguably the most popular destination in the world to see wild wolves — as crucial in dispelling myths about the species. Wolf-centered tourism can help more people see the creatures, or at least signs of them, which helps grow support for conservation as people witness what he calls “the power of wild places.” But sustaining that requires a stable enough wolf population to support both consistent wildlife-viewing opportunities and a permanent commitment from tour companies.

He’s seeing how the growth in wolf tourism is reshaping the economies of Yellowstone gateway towns. He points to nearby Gardiner, which used to be a popular place for elk hunters every fall. While hunting remains a draw, he believes it now likely takes a backseat to wildlife enthusiasts, or “non-consumptive users.” Still, Stahler echoes what Taylor of Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures believes: both hunters and wildlife watchers share an interest in maintaining a healthy food web, including a stable wolf population. And Yellowstone’s 3,472 square miles is key to preserving those populations.

The park has seen an increase in visitors and a corresponding increase in tour companies in recent years, as well as related increases in sound pollution, environmental damage at road pullouts, and congestion at campgrounds and viewpoints when wolves are nearby. Fortunately, Stahler notes, the majority of human activity occurs along road corridors, which account for only a small fraction of Yellowstone’s total land area.

Yellowstone spans more than 2.2 million acres, and roads cover only a small percent of that, with just 251 miles of road arranged in a figure-eight pattern. The layout allows the park to maintain largely undisturbed wilderness landscapes for wolves while accommodating growing numbers of visitors who stick primarily to paved areas. That allows more tourism spending to come into the park and its communities, while still keeping people concentrated in a relatively small area.

“I think of it as, you have your human-wildlife interface along the road corridors,” Stahler says. “But as you move away from that road corridor, it becomes increasingly, increasingly wild.”

Camaraderie in the wild: The wolf watchers of Yellowstone

Wolf crossing road in Swan Lake Flat, Yellowstone National Park. Photo: NPS/Jim Peaco

I spent the next three mornings waking up at 4 AM, making the one-hour drive from Gardiner into the Lamar Valley in total darkness. For all the talk about Yellowstone’s overtourism issues, I saw more elk than people by a large margin — one of many reasons to enter the park extremely early.

On my first evening in Yellowstone, I randomly struck up a conversation with another wolf-watcher named Dan, a contractor from Ohio and an avid wildlife enthusiast. He was spending two weeks camping at the Slough Creek campground in Lamar Valley and was friendly and generous, offering the use of not only his spotting scope but also snacks and lawn chairs. We crossed paths again the next morning, and it became our routine for the next few days to meet up each morning and evening in the same location, spending hours observing wolves as they monitored an injured bison nearing its death. While watching the struggling bison was difficult, such scenes are common in late summer and fall, when male bison sustain injuries during mating competitions. These weakened animals are a crucial food source for predators, particularly grizzlies, who need to build up fat reserves before hibernation.

Each morning and evening, we watched members of the Junction Butte wolf pack emerge from the treeline to feed on a bison carcass perched on a hillside above the injured bison. The carcass was the work of a large grizzly, who made regular appearances at dawn and dusk. Weighing close to 600 pounds, the bear dwarfed the agile gray and black wolves, causing them to scatter upon his arrival — but never too far. A small group of adult wolves has roughly the same weight and predatory ability as a grizzly, and the two sides seemed to have reached a temporary detente, coexisting as long as the food supply lasted. From our vantage point more than half a mile away, it was nearly impossible to see them without binoculars or, better yet, a high-powered wildlife scope.

During these hours, I met other travelers who had come to the park exclusively to see wolves. Among them was a newlywed couple from Utah, visiting Yellowstone for the third time but seeing wolves for the first time. When I asked if they would return now that they’d achieved their goal, their answer was “probably.” I also met a family from the UK, in the midst of a two-week wildlife tour of national parks in Utah and Wyoming, and Bill, a lifelong Yellowstone wolf enthusiast who could identify individual wolves by their unofficial nicknames. (Park staff identify wolves only by numbers, each ending with “F” for females or “M” for males.). He spends weeks in the park each year, has met many of his closest friends through the hobby, and has started to become an advocate for wildlife conservation in the American West.

I spent several early mornings and late evenings in the Lamar Valley, chatting with my fellow wolf watchers. Photo: Suzie Dundas

It’s clear the veteran wolf watchers enjoy sharing the enthusiasm, and Dan, the newlyweds, and Bill were all more than happy to let passersby take a peek through their scopes. The wolves knew we were there watching them from a distance and occasionally raised a bushy eyebrow to glance at the roadside gallery when a car alarm sounded or a child shouted too loudly. But otherwise, we weren’t of much consequence. As Stahler suggested, perhaps the wolves have come to understand that humans stick to the roads, and the rest of the landscape is theirs.

Through the scopes, we could clearly observe the wolves tearing into the bison carcass, their snouts wrinkling as they pulled at the hide, pieces of flesh swinging while ripping away meaty chunks. Brutal as the scene was, it was hard not to see the similarities at moments between wolves and the large, domesticated dogs we keep as pets — especially when the grizzly reappeared and the wolves scurried off, prancing away with a playful gait and fluffy tails swaying side to side.

The big, bad wolf — or the big, bad ‘touron?’

Downtown Gardiner, Montana. Photo: Suzie Dundas

Many of the wildlife and wolf-spotting guides operating in the park live in Gardiner, Montana. It’s one of several gateway towns for sprawling Yellowstone National Park, but none have a closer tie to the park than Gardiner — literally. The national park boundary is so close to downtown that while Gardiner’s shops and storefronts are in Montana, the awnings and sidewalks are part of Yellowstone National Park. “There used to be a lot of bars there, and you had to be careful,” jokes Dennis McIntosh, president of the Greater Gardiner Community Council (GGCC). “You’d step out of the bars after one too many, and whoops — you’d be on federal property.”

Today, Gardiner’s once-rowdy bars have been replaced with t-shirt stores, restaurants, and other shops serving the occupants of the 500,000-plus vehicles per year that enter Yellowstone via the north entrance. It’s the only of the park’s five entrances open year-round, and since wildlife watching is easiest in the winter, it serves as the de facto hub for the park’s winter wolf watchers.

Gardiner was established in the late 1800s after a resident living within Yellowstone’s borders was “asked to relocate,” as McIntosh diplomatically puts it, settling just beyond the park boundary in Montana. Likely involved in trapping or poaching, the individual clashed with park authorities — a tension that, McIntosh notes, lingers in the town ethos today. Over the years, there have been numerous points of contention between Gardiner and Yellowstone: how to route the railroad through town, whether or not to allow cars in the park, disputes over the precise location of the park boundary.

View this post on Instagram

The latest conflict, though not the only one, is the presence of wolves in and around Gardiner. While wolves do cause issues, particularly when they prey on livestock or horses from nearby hunting lodges, the real debate stems from the economic impact of wolf tourism. Gardiner’s proximity to the Lamar Valley makes it a prime destination for wildlife watchers, attracting deep-pocketed photographers who often hire guides for a week or more at costs of up to $1,000 per day. It funnels millions into Gardiner’s economy each year, and during my August visit, even my extremely budget motel was nearly $300 a night.

That tourism influx brings serious challenges, and McIntosh’s Greater Gardiner Community Council focuses primarily on addressing issues that affect residents, such as housing shortages and infrastructure strained by the town’s growing visitor numbers. He estimates that 80 to 90 percent of Gardiner’s population is employed in tourism, most of which depends on the park, though a small portion still supports hunting due to the town’s location along the migratory path of Yellowstone’s elk. As a result, he describes the local reaction to the 1995 wolf reintroduction as “mixed,” with some seeing the economic benefits while others voiced concerns about the impact on nearby ranches and the ways in which it would change the town.

“There’s still, and there will always be, contention over that,” McIntosh says. However, he believes the town generally embraces a mindset of “mutual tolerance” toward wildlife, pointing to examples like bison and elk herds taking over the local school’s sports field during football games. (Turning on the loud lawnmower usually seems to scare them away, he says.) Like Stahler in Yellowstone, McIntosh recognizes that wolf-watching tourism is a major economic driver for Gardiner. He notes that when the park increased commercial use permits, the number of photography and wilderness guides in town surged. In winter, he adds, wildlife watching is the town’s “bread and butter,” largely fueled by wolves. Come December, “the bison are moving around, the bears are sleeping, the cats nobody ever sees,” he says. “But the wolves just kind of stay put.”

Bison grazing on the Gardiner, Montana, school football field. Photo: NPS/Jim Peaco

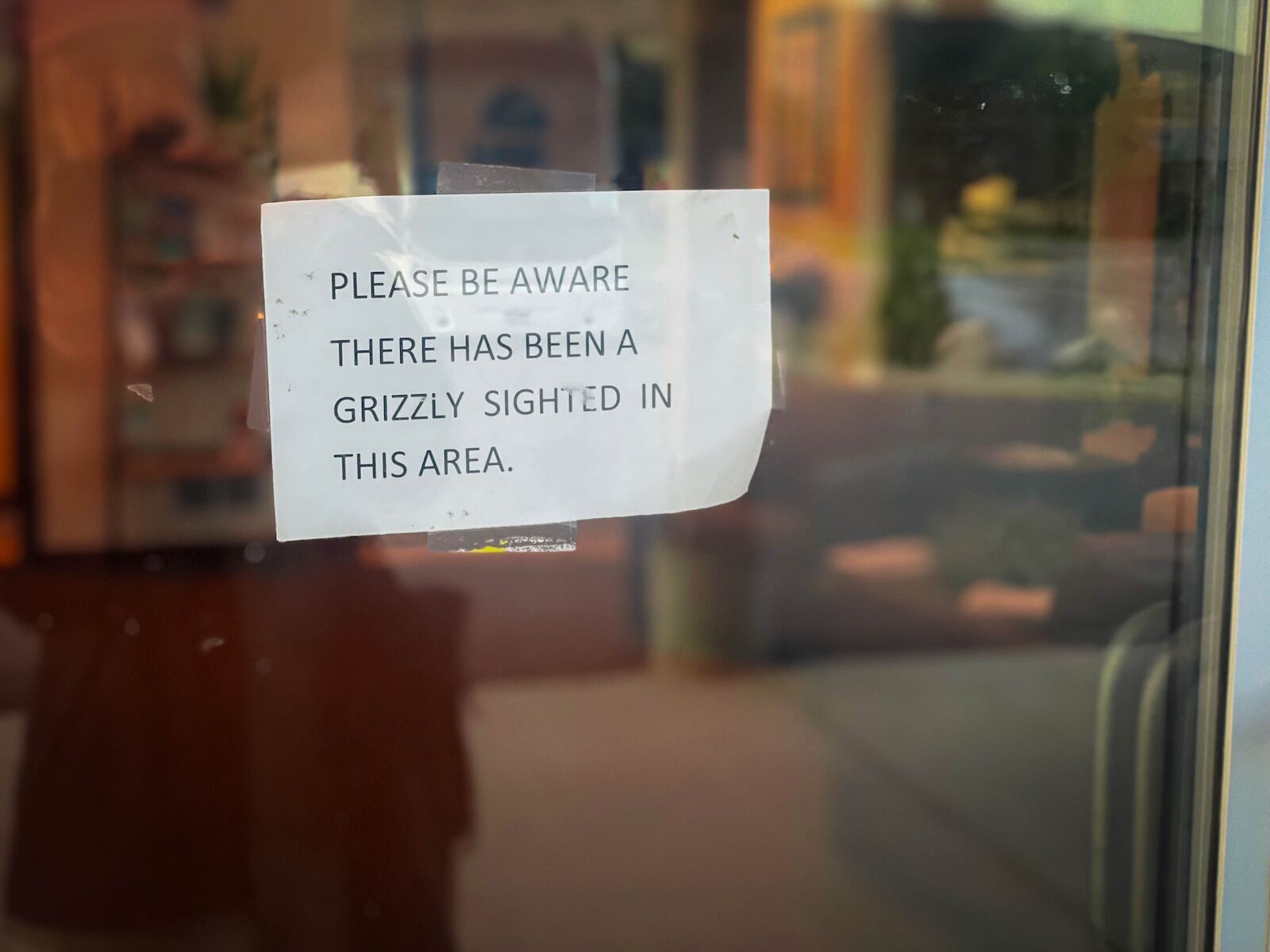

Despite this, they’re actually the least seen of the area’s large animals, McIntosh explains. Human encounters with bison and grizzly bears are far more common — a fact easy to believe, based on the “grizzly in area” warning sign posted on my motel door the day before. Yet, despite fewer direct interactions, wolves still carry a negative reputation.

“You know, they have this ‘big bad wolf’ mentality,” McInstosh says of how people think about wolves. “That concept is still out there.” So on the rare occasion wolves do appear, such as when the park’s 8-Mile Pack killed an elk on school grounds, the incident garnered national attention. When there are concerns about public safety and wildlife, the GGCC can alert authorities like Yellowstone management or Montana Fish and Game, but can’t themselves set any policies or new laws.

A grizzly warning sign on the door of the author’s motel in Gardiner, Montana. Photo: Suzie Dundas

What the town can do, he says, is trust that those making decisions about conservation, hunting quotas, and population management are guided by science. It’s still controversial, though he thinks that’s part of Gardiner’s DNA. “These days, there’s contention with everything: outfitter to outfitter, tourist to tourist, pizza shop to pizza shop,” he says. Still, he believes the town has grown more accepting of both wolves and the science behind management decisions compared to past decades.

“The problem is that everyone thinks they know what the right thing is,” he explains. “Certainly, if my business is taking pictures of wolves, and bringing people to take pictures of wolves, it’s counterintuitive to think that hunting wolves is the right thing. And then there’s hunting guides, people who make their living off the land. They just don’t want their horses to get eaten.”

One issue where there’s little debate, however, is the problem of “tourons:” a portmanteau of “tourist” and “moron,” coined in Yellowstone to describe the park’s most irresponsible visitors. The popular Instagram account Tourons of Yellowstone, with more than half a million followers, regularly posts content showcasing reckless behavior, most of it involving inappropriate and dangerous interactions with wildlife.

“People tend to lose their minds when they’re on vacation in a cool place, and Yellowstone is a really cool place,” says McIntosh. “They’re stopping in the middle of the road. And opening their doors in the middle of the road and stopping traffic. Nowhere anywhere else would that person ever think of doing that. But the awesomeness of the park makes people lose common sense.” He equates Gardiner’s growing tourism problems to a sponge.

“And once you oversaturate a sponge, what happens?” he asks. “Things just run everywhere.”

McIntosh worries that the town, which spans less than four square miles, risks becoming overwhelmed if Yellowstone’s visitor numbers continue to climb. However, Gardiner is currently collaborating with park managers, tourism companies, and local land managers to address the challenges posed by the rise in wildlife-driven tourism. While an increase in winter and shoulder-season tourism could offer some relief, fewer businesses remain open during the colder months, and winter visitors tend to spend less time outdoors, leading to reduced foot traffic for shops and restaurants. That means that winter wildlife watchers don’t have the same economic impact as that of families and summer tourists.

“There’s a lot of contention around grizzlies. But for some reason, the wolves, at least anecdotally, seem to get a worse rap.“

— Dennis McIntosh, Greater Gardiner Community Council

For McIntosh, it’s not possible to say whether having wolves nearby is beneficial or detrimental — it’s just how it is. While he understands the arguments on both sides of the debate over increasing their population, he clearly sympathizes with the way wolves are often misunderstood.

“Wolves have this storyline,” he says. “They travel in packs. They’re intrusive. They’re mean. And I think everyone knows grizzly bears are bigger, and can do a lot more damage, but there seems to be more contention around wolves than grizz. And there’s a lot of contention around grizz. But for some reason, the wolves, at least anecdotally, seem to get a worse rap.”

The proponents, the opponents, and the truth

Photo: Jackson Hole Wildlife EcoTour Adventures/Josh Metten Photo

After speaking with a range of individuals connected to Wyoming’s wolves — biologists, land managers, tour guides, and residents of gateway towns — I was struck by how moderate the views of those most involved in the wolf debate tend to be. In states like Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana where hunting is prevalent, the overlap between conservationists and hunters is far greater than the divide. Like Mills explained to me in the field, most cases of illegal wolf killing result from a hunter accidentally crossing a boundary or failing to report a kill within the legal window, rather than an intentional act of hostility.

When it comes to the economic impact wolves have on the tourism industry and beyond, the reality likely falls somewhere in the middle. However, most stakeholders — even those who are hunters themselves, as so many in Montana and Wyoming are — seem to agree on some level that wolves provide intrinsic, intangible benefits that can’t easily be quantified on a fiscal spreadsheet. These broader, less tangible contributions to the ecosystem and the visitor experience are difficult to capture in purely economic terms.

Wolves play a crucial role in maintaining healthy ecosystems, preventing overinflated herds that can spread disease and reducing the likelihood of desperate, unsustainable behaviors among prey and predator species. Protecting wildlife like wolves is central to the National Park Service’s mission to preserve natural resources for future generations. And beyond the ecological importance, mega-predators like wolves provide invaluable insights for scientists, deepening our understanding of natural systems and the human impact on them. Valuing wolves also reflects a broader societal commitment to correcting past wrongs and mitigating the often harmful effects we’ve had on a natural world millions of years older than modern-day humans.

Yellowstone National Park’s Grand Prismatic Spring is one of many natural wonders preserved from human development within the park. Photo: Suzie Dundas

Making a decision about the permanent future of a species based on any one factor, be it economic, tourist, ethical, or industrial, is a near-guaranteed way to polarize the public, all of whom have an equally valid say in the future of their country. As Mills told me before we parted ways, “We should see the richness of having them, but their existence shouldn’t overrule anything else. But there’s this intangible impact, the cultural impact. Our landscapes are better just because they’re here. This valley is more wild because wolves can live here.”

In Yellowstone, Stahler — perhaps the man most in tune with the current state of wolf reintroduction in the US, and certainly the man in charge of defending the future of wolves in public spaces — put it even simpler:

“We see a spectrum of people that really hate wolves, and that wolves can do no wrong,” he says. “And somewhere in the middle is the truth.”