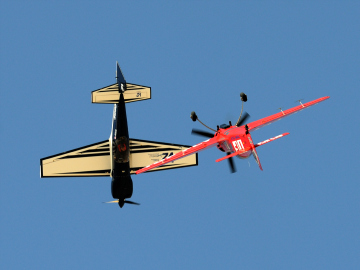

All photos courtesy of Flying Aces Ltd.

TEN YEARS AGO, Jeff Zaltman was a manager of mergers & acquisitions for Ford-UK in London. He was also an amateur pilot whose access to Europe’s aviation circles had shown him just how little attention aviators got in mainstream motorsport.