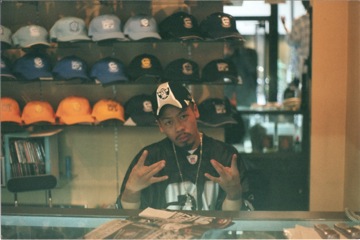

Photos: author

Whenever I meet someone who has been to Japan for any amount of time a superficial bond is instantly formed. The script begins: Where were you living? How long were you there? Were you teaching English? What company were you with? These conversations eventually turn into personal experiences about the struggles of daily life for a foreigner in Japan, and what it was like in the first few weeks after arriving (or surviving).