When we travel to a new place, we take everything in. We observe, we taste, we smell, and we listen.

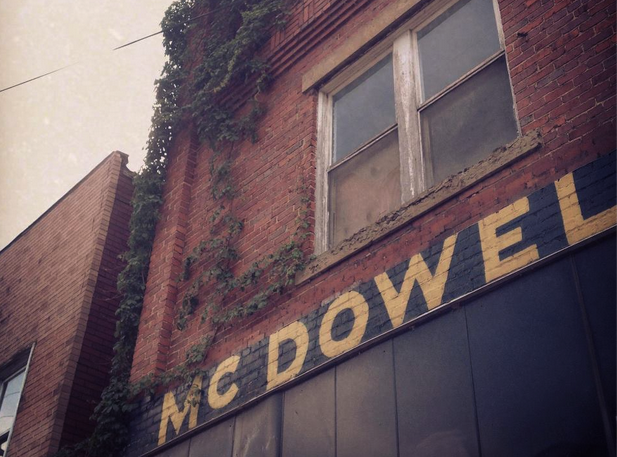

As a native of West Virginia, and now resident of Boston, I always look forward to traveling back “home” to reconnect with the place. Those lush, tree-covered Appalachian Mountains embrace visitors as they travel the winding roads that lead to interesting places with unique histories and welcoming faces. In the morning, we watch the fog slowly rise out of the valleys and listen to the crickets sing their evening song in the fields. And while West Virginia is a place filled with interesting sights and sounds, it’s a place many will never visit.