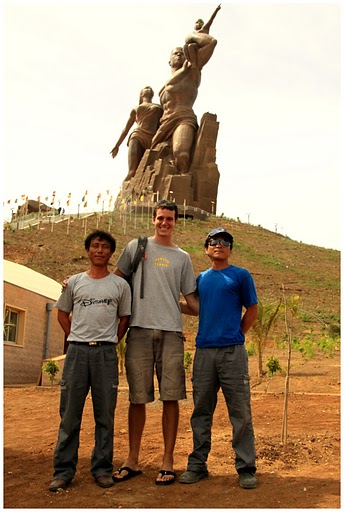

WHEN RUSH HOUR HITS in Dakar, it’s best to avoid any horses. After some strained acceleration, we made our move past the rickety cart and its whip wielding chauffeur as we pulled off the highway and into the lot. I heard the battered yellow taxi rattle when I stepped out of it and he stood before me – the 160-foot bronze warrior of the African Renaissance.

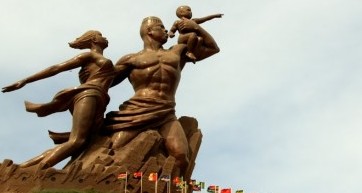

A giant of a man with a look of steely determination and rock hard abs, he emerged half-naked from the stone, breaking free of his bonds to lead his family into the future. Atop his shoulder sat his son, a young boy who shared his father’s stern face, confidently pointing the way to their salvation. Only the wife seemed less than prepared, the imaginary wind of her husband’s efforts working against her wardrobe to both reveal her thigh to the hip and leave a full breast to reign over the hazy cityscape. My eyes kept drifting to the exposed nipple.

The African Renaissance Monument rises over Dakar as the tallest statue in the world outside of Asia and the newest man-made attraction in Senegal, the first step by President Wade in heralding an African renaissance of art and culture. It easily dominates the skyline, which consists of mainly two-story buildings, but the statue does its best to help you forget that it is thirteen feet taller than the Statue of Liberty. Situated on a squat hill above sandy suburbs, the bulky foundation seemed to subdue its actual size and its fresh, shiny bronze gave the impression of a plastic hollowness.

Standing in the parking lot, I couldn’t help but wonder if they had made a mistake with its orientation. The statue’s scantily-clad buttocks faced any observer viewing from Dakar’s downtown plateau, and the child signaling the hopeful way of Africa pointed north, toward Europe.

The ticket stall not yet in operation, I made my way straight to the staircase that climbed to the monument base, avoiding eye contact with the security guard just in case he had his own policy. Flags of each African nation lined the steps on either side, fluttering in the ceaseless wind rolling off the ocean cliffs a few hundred meters westward. Though less than two months old, the wind had already begun to unravel them; the majority looked half-eaten.

Once at the base of the statue, I headed to the large doors embedded in the rock face only to find the top of the monument closed off to the public. Nevertheless, the foot level viewing area provided a spectacular vista of the sprawling Dakar peninsula, and the multiple personalities of the modern yet impoverished city were easy to denote. To the south lay an outdated plateau district, offering a glimpse of a colonial past and home to Senegal’s few high rises. The suburbs of Almadies, in the north, were colored by a combination of upscale beach-side hotels, clubs, and NGO housing. And straight ahead, in the center, facing the statue, sat the dusty and dirty heart of Dakar, a sea of white-washed cement quartiers, heavily littered streets, and abandoned construction that gave the air of an unending work in progress, a city attempting to reach a goal it’s not quite sure it still sees.

With such visible disparities, the $27 million monument price tag may be hard to justify for some, but the audacity of President Wade’s initiative deserves at least a little respect because a huge fucking statue is probably more likely to attract international attention and commerce than something boring and practical like mosquito nets to fight malaria. Less understandable is his claim to 35% of the tourism profits and the actual design of the statue which has almost zero trace of African influence. The gratuitous nudity is strikingly at odds with the character of this Muslim nation (the breast was soon covered due to a protest by the Imams in the weeks following my visit), and the art styling itself has more in common with Stalinist architecture than Senegalese, due largely to the contracted designers – the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea. I don’t know how the partnership came about but assume the decision came down to a limited competition among all the best massive-statue-making entities. After all, if there’s one thing communists know, it’s monument making.

As the statue inauguration day approached, I returned to the village where I worked, a collection of huts on a sparsely traveled crossroads at the far eastern end of the country. No electricity didn’t mean we couldn’t share in the celebration, as before long a solar charged car battery was brought out and hooked up to a TV with a long bamboo pole antenna. With the children relegated to front floor seating, I took my honorary foreigner seat among the village elders.

Sensing an easy opportunity to fit in and earn a few cheap laughs, I cracked a few jokes about the clearly ridiculous and now nipple-free statue and the non-existent movement it claimed to portend. The resulting silence was shaming and I went quiet as all eyes followed the lighting of the monument and the singing of the African anthem, and the oldest to the youngest united in a communal moment of pride. As the crowd cheered the finale, my good friend and host brother turned to me with a smile on his face.

“Even the Eiffel Tower was once considered ugly, but now it is the jewel of France. Perhaps the same will happen here.”

I nodded in agreement and considered the likeliness of this occurring. He sensed my skepticism and laughed as he clapped my hand.

“And if it’s not like that, at least our lady is prettier than your Statue of Liberty.”

She’s definitely got us beat on the dress.