IF IT’S FOR SALE, YOU CAN FIND IT IN WEKALET AL-BALAH, the Date Market. Unlike its name suggests, the market specializes neither in dried fruits nor romance. Instead, the Date Market is a 24-hour, open-air, semi-organized yard sale that has grown up out of the streets of Bulaq Al-Dakrur, a neighborhood in Cairo.

Each section of the streets in Wekalet Al-Balah specializes in a different good. There are the requisite fruits and vegetables to be found in any Cairo market: fresh mint; bruised guavas; cucumbers covered in a layer of dirt from the Nile delta farms (if you’re a romantic), or the layer of exhaust that ends up covering everything in Cairo (if you’re realistic); whole sides of beef, the tail still attached and the skin striped with red to signify it’s Halal, dangling from butcher shops.

Further on, herds of live goats munch on garbage in makeshift pens next to chickens pecking at the ground. In one stretch, a young couple peers inside used refrigerators for sale, imagining their future contents. Down the street, guys look over a line of gleaming Chinese motorbikes, which give way to a section where men strip wire and dissect old car carcasses for parts. Shoppers step around a burning radiator that smolders in the street, giving off clouds of carcinogenic-smelling smoke.

Life in the houses of Bulaq mixes with the market — shrieking kids jump on a rickety-looking trampoline and wait in line to climb onto a rinky-dink carnival ride, its once-brightly colored paint covered in rust. Women lower baskets down from third-story windows and, once full of cabbage or soap or boxed milk, pull them back up again. Laundry hung out to dry could be mistaken for a sale display.

The part of the market that most Cairenes think of when they refer to Wekalet Al Balah is the section along 26th of July Street, a busy thoroughfare where the edge of the market meets downtown Cairo. Here vendors compete for sidewalk space with their hundreds of racks of secondhand clothes for sale, shouting the prices over Cairo’s constant background of honking horns, construction, calls to prayer, and tinny music playing from cell phones. Cast-off jeans, underwear, house dresses — it’s all here, and it’s all under five dollars.

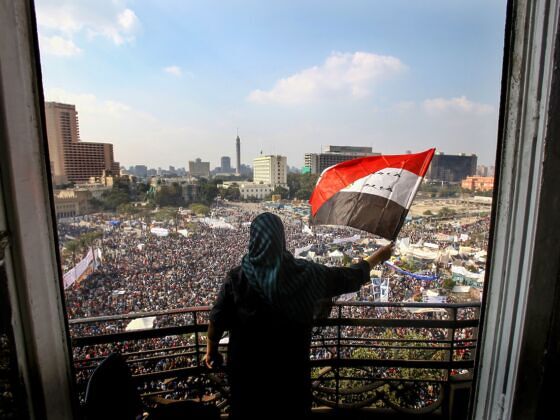

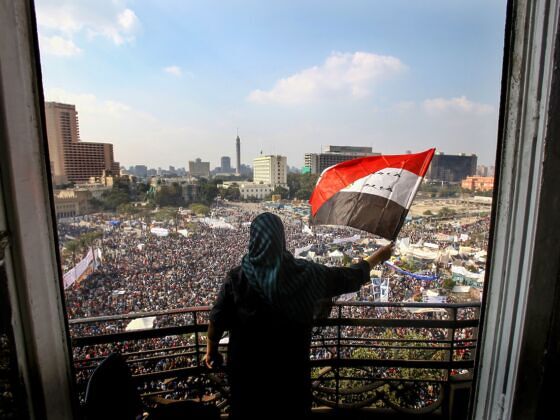

Located just one subway stop away from Tahrir Square in the heart of Cairo, the decidedly folky Wekalet al-Balah has long been the site of a tug-of-war between the Egyptian social classes, the government, foreign developers, and the people who live and work in its markets.

As it has altered many facets of life in Cairo, the revolution has challenged all of this. Today, Wekalet al-Balah is emerging as a symbol of revived Egyptian independence.

Nasser, though, a middle-aged man with stained teeth who wears a heavy overcoat over a clean white shirt, claims to have a mental map of the whole thing.

“My mind is sharper than a satellite, better than a laptop,” he tells me, standing in front of his used clothes shop. The white storefront is dirtied with dripping, faded hand prints and Allah written in blood, remnants from an Islamic tradition of sacrificing an animal on the holiday of Eid Al-Adha and smearing the blood on a new business, home, or car for good luck.

“And I love love love my work,” he says, bringing his hand to his chest. “That’s why I succeed.”

Nasser was just a kid when he came to Cairo from his village in Upper Egypt to sell clothes on the sidewalk. It took him years of working nonstop, sometimes for four days without sleep, to acquire the three shops he now owns in the Date Market.

“Ya Abdou! Get back to work!” he calls to one of his workers who leans against the wall, texting.

“Saidis are the hardest workers,” says Nasser. Saidi is the name for people from Upper Egypt, explains my friend Ahmed, who translates when the conversation moves beyond what my cab-directing and juice-ordering Arabic can handle. Saidis are often the butt of city-dwellers’ jokes, which are akin to American “redneck” jokes.

Most of the workers in the Date Market have migrated from Upper Egypt, which is, counter-intuitively, the southernmost area of Egypt on the border with Sudan. Saidi transplants leave families behind in the hopes of making a living in Bulaq by selling used clothes. Those who don’t live in Bulaq live in Imbaba, a crowded slum which houses over one million people. Nasser’s wife and four children still are at home in his old village, and he only has the free time to visit them every one or two months, he says.

“We’re not like the people from Cairo who work all day and then go home and rest when they get tired. We have to work with our hands because we don’t have an education,” he says. “But we succeed because we have dreams.”

Nasser starts to expound on the superiority of the work ethic of Saidis over Cairenes, but is distracted by a group of guys hustling with their racks of clothes down the street.

“Beladeyya?” I ask, referring to the local police, who used to be notorious for giving Wekalet Al-Balah used clothes-sellers a hard time because of the unofficial nature of the market.

But the source of the disturbance outside Nasser’s shop isn’t the beladeyya this time, which becomes clear as a crowd forms down the street around two men shouting loudly. One of Nasser’s workers rushes back and tells him there’s a fight between two vendors because one got too competitive with another and broke his rack.

Like a tussle in a cartoon, a cloud of dust rises around the scuffling men as more guys join the fight, and things start to fly through the air: bottles, pieces of wood, hangers. Suddenly there’s the unmistakable sound of a gunshot.

Nasser sends Ahmed and me into his store, and he and his workers race to bring all of their goods inside. I try to put as many racks of faded denim between myself and the open door as I can.

When I was considering coming back to Cairo after studying abroad here in 2009, this was just the sort of post-revolution ‘volatility’ I’d heard reports of in the news. I dismissed it as media overblow, and until this point that had been my experience; I’d only witnessed a peaceful march on International Women’s Day and the gatherings in Tahrir that have happened every Friday after mosque since the revolution.

As six or seven more pops ring out, I’m forced to rethink the confidence with which I’d dismissed the possibility of violence. The people who were shopping when the fight broke out, though, seem remarkably unfazed; two ladies come off the street into the store, but inside they continue their shopping, comparing pairs of pants with just a few curious glances toward the door.

“Don’t worry,” Nassar says to me, noticing my obvious fear. “They’re just firing into the air to try to scare one another or break up the fight.”

Nasser’s brother runs back into the store with blood coming from his temple. He’s been hit on the head with a piece of metal, but luckily it’s just a small wound. Someone dashes to the café down the alley and comes back with a handful of used coffee grounds, which they rub into the wound: a shaaby, or folk, remedy to stop bleeding, Ahmed explains.

Ahmed and I wait on wooden chairs, drinking Pepsis from glass bottles. The commotion starts to gradually move down the street, and we peek outside to watch from a safe distance. A trio of older men stand on the curb, looking on with us. One of them turned and noticed me.

“A tourist is watching!” he says, elbowing the others. “My god, what a scandal!”

“This is Egyptian civilization,” adds one of the others, pointing his hand down the street.

“What would Obama do?” asks the third.

When it’s safe for Nasser’s workers to wheel their racks back into the street, Ahmed and I head down to the other end of 26th of July to ask other vendors if they saw what happened during the fight.

“Which fight?” asks one of them. I excitedly tell him there was a big fight with guns right down the street from his.

“Ah, that’s normal,” he says dismissively. “After the revolution it happens so often, we don’t even notice it anymore.”

After the revolution

Though nothing has changed about Egyptian hospitality and honor (a week before, a cab driver pulled a u-turn in traffic to return a 100-pound note my friend and I had mistakenly given him, thinking it was a 10), there’s a palpable sense of tension beneath the surface of Egyptian society. I can’t be sure if on my second trip to Cairo I’ve witnessed more petty street fights and shouting matches than I ever remember before, or if I’m just more aware of them now, but the violence in the Date Market ended up being the first of two incidents involving guns I witnessed in a little over a month in Egypt — the second was a road rage fight between cab drivers in Alexandria.

Cairenes talk about the increasing presence of concealed weapons, and my heart leaps whenever I hear the menacing electrical cicada sound of tasers, which are now openly sold on street corners with nail clippers and underwear. In the constantly teeming streets of downtown Cairo conflicts between people are inevitable, but these days they seem to escalate to blows more quickly, and there are fewer police around to break things up.

That tension and the fight in the Date Market are understandable; more than a year after their revolution, many Egyptians find themselves in similar, if not in some ways worse, circumstances as before January 25th. More than once, I’ve even heard the revolution called “bullshit.”

This is not to suggest the majority of Egyptians feel like the revolution was unsuccessful, but rather that it’s simply still ongoing — the protestors haven’t gotten all of the things they asked for yet, and this means there are many unresolved issues for Egyptian people to feel angry about, especially the people in Wekalet Al-Balah and Bulaq.

The chunk missing in Cairo’s skyline

I’m far from the only foreigner drawn to the area; one of Bulaq’s earlier admirers was Napoleon Bonaparte. When he came to Egypt in the 18th century, he called the area beaux lac, or beautiful lake, which was arabicized to Bulaq. The district had been well known as Cairo’s major port since the 14th century, and some of the many things traded there were dates (hence the name).

25 years ago or so, there were only a few secondhand clothes-sellers in the market, but enterprising businessmen caught on to the demand for cheap clothes, and more and more racks and piles crowd the sidewalk all the time.

Since I first started coming to the Date Market two years ago, its used clothes section has spread up 26th of July Street nearly to the Gamal Abdel Nasser metro station and the steps of the High Court building, filling the sidewalks with secondhand hawkers almost to the point of impassibility.

Bulaq’s former role as Cairo’s major port is reflected in the ancient and often neglected commercial and Islamic monuments tucked into the Date Market’s side streets. I got a sense of the medieval Bulaq the first time I was brave enough to leave the market’s main drag and search for Hammam al-Arbaa, a 500-year-old bathhouse where modern Cairenes still soak. I got lost, of course, but was pointed the way by artisans, who looked up from hammering and sawing in their centuries-old, soot-covered workshops, and their wives, who leaned out of the windows in the apartments above.

This is the kind of frozen-in-time, transportation-to-Arabian-nights past that Khan Al-Khalili, the kitsch-heavy tourist market in Old Cairo, tries to manufacture. For centuries Khan and Bulaq rivaled each other as the city’s main economic centers, and today foreigners flock to Khan to shop for pyramid t-shirts and puff on overpriced shishas. Its equally ancient and exquisite buildings have nearly been obscured by kitsch, but because of the tourist presence they’ve also been lovingly preserved. Unlike Khan Al-Khalili, Bulaq — while economically important today because of its ironwork quarter along the Nile and the textiles trade — is visibly untouched by tourism dollars.

It’s just that untouched quality of Bulaq that has put its inhabitants under threat for the last 25 years, says Dr. Nelly Hanna, an Egyptian historian who has written extensively on the area.

“Bulaq is prime real estate because of its river location — everyone wants a Nile view — and because it’s so close to downtown,” she explains.

There’s a chunk missing in the skyline of the Tahrir side of the Nile with its ministerial buildings — Maspero, the monolithic media headquarters; the empty and burned-out shell of the NDP offices; five-star hotels; and the Nile City Towers, whose tenants include a cinema, shopping center, and AIG Egypt offices.

Bulaq, and the Date Market that comes right up to the edge of the Nile, fills that chunk. A stretch of low, homey, and often crumbling buildings, it remains the last undeveloped area in the heart of Cairo.

“International investment companies have a desire to wipe it off and build a modern, more commercially viable center,” says Dr. Hanna.

The neighborhood was recently the focus of a short documentary with the same name by Italian filmmakers Davide Mandolini and Fabio Luchinni. Sayed, a Bulaq native who appears in the film, sat behind me at a screening. Stumbling over his English and the sound system feedback, Sayed told the audience how Mubarak’s government officials, urged on by deals with foreign companies, were allowed to evict residents from their homes if they showed any signs of deterioration, using the excuse that the dwellings were unsafe. Residents were relocated by the government to an area called En-Nahda, a block of cement apartment buildings on the edge of the desert.

“They went there and they found that there were no windows, no faucets, no real bathrooms,” Sayed said.

Just a month before the revolution in 2011, police evicted many Bulaq families in the middle of the night and left them on the street with nothing but a single blanket. After this history of mistreatment, the residents of Bulaq joined the protests of the revolution with a particular bone to pick with the government. During the clashes of the ‘Second Revolution’ in November, banners in Tahrir read, “The men of Bulaq Al-Dakrur are coming for martyrdom.”

“We got some weapons from the bosses who own the shops here and we made teams to defend our streets,” recounts Mohamed Kebir. “We were like one family.” The people of the neighborhood around the Date Market sheltered activists in the winding alleyways that branch off the market street, giving them food and vinegar to protect themselves from teargas. Mohamed Kebir says the thugs that terrorized and looted more upscale neighborhoods like Zamalek and Mohandesin didn’t dare enter Wekalet Al-Balah. “Those neighborhoods needed police protection, but we defended ourselves,” he says.

It makes sense that the Date Market would’ve policed itself during the revolution; residents’ and vendors’ relationships with the local police force have always been tenuous, with a history of harassment by the beladeyya. Selling anything on the street in Cairo is technically illegal, although the enforcement of this law is mostly laughable — one would be hard-pressed to find a corner of Cairo where something isn’t for sale. The beladeyya have had such a presence in Wekalet Al-Balah, the workers tell me, because of its improvised nature, the class connotations of the people who work and shop there, and its location amid more developed parts of Cairo.

More than once I’ve been shopping in the market when all of a sudden shouts of “beladeyya!” echo down the street from vendor to vendor like a game of telephone. Within seconds, a pull of strings will bundle up a tarp and its contents onto the back of the vendor, who jogs out of sight. The metal racks, fitted with wheels for quick exits, whiz inside the shops or down an alley.

Any unlucky vendor left behind often has his goods confiscated and has to go down to the police station and pay a hefty fine to get them back. All of this is avoidable with the right bribe, of course. The chaotic nature of the neighborhood can be viewed as vibrant or unruly, but it’s this unpredictability that the beladeyya wish to dampen, and just another one of the excuses the government has used to justify its attempts at gentrifying Bulaq.

Maybe because of these threats from the outside, Bulaq residents have bonded together perhaps more than in any other area of Cairo. I hear this sentiment echoed over and over by the workers at Wekalet Al-Balah. Bulaq, they say, is unlike an anonymous, modern neighborhood — instead, the residents, many of whom have been here for generations, have close ties with one another.

“We have only been friends for two years, but we are like brothers,” says Mohamed, touching his two index fingers together. Mohamed Sogayyar tells me that the two had only known each other for a few days when Mohamed Kebir came to his defense in a street fight. They’ve been close ever since, and, Mohamed Sogayyar says, “he’s by my side in everything.”

He goes on, “I grew up here. I have relatives in the neighborhood, and all of my friends work here, too.” As we walk together between the racks of clothes, other vendors call out to Mohamed and Mohamed, and they stop for a few minutes to chat.

Shaaby City Stars

Traditional Egyptian fashion for men is the galabeyya, a thin, floor-length robe, and for women the abaya, a loose, black dress that’s draped over the head and body and offers in modesty what the galabeyya does in breathability. While these styles are still popular among the older and poorer Egyptians, these days most Cairenes prefer Western fashion. American and European brand names are widely known, if mainly by their bungled knockoffs — Dansport, Adidas with four stripes, gym socks baring the names of both Givenchy and Versace — and desirable.

New Western designer clothes are only easily found in one place in Cairo: City Stars Mall. An $800US shopping megalopolis located near the airport, it has a theme park and hotels in addition to its countless brand-name boutiques. Shoppers pass through metal detectors to reach the gleaming stores selling fashionable mini-dresses, tube tops, and sheer blouses that are hard to imagine wearing on the streets of Cairo.

City Stars is the icon of Cairene modernity, a dream inaccessible to the common man, or shaab, who would do his shopping at Wekalet Al-Balah. Shaaby is an Arabic adjective perfect for describing all things folksy and “of the people,” from clothes and foods to neighborhoods and music.

“When people buy new clothes it’s a million of the same t-shirt,” says Hilali, a Date Market clothing vendor. “But they come to Wekalet Al-Balah because here they can find unique things, designer things, for cheap.”

It’s true; for those who are willing to dig, it’s easy to find good-quality, if a few seasons old, pieces from high-end Western labels like Gap, United Colors of Bennetton, and Marks & Spencer among the holey jeans and grandma sweaters.

Hilal, another vendor, jumps in — “It’s the shaaby City Stars!”

By making the brand-name duds we have too much of in the U.S. available for cheap, the Date Market offers poor Egyptians, whether they’re conscious of it or not, the opportunity to literally try on the lifestyle that these brand-name costumes connote, no matter how incongruous it might be from their own.

But the past lives of the clothes at the Date Market keep wealthier Egyptians shopping at City Stars, thank you very much. And it’s mind-boggling for most middle- and upper-class Egyptians that any foreigner would set foot in Wekalet Al-Balah.

“You get that other people wore those clothes, right?” Marwa, an Egyptian university student, once said to me with undisguised disgust. “Well, I hope you wash them.”

When I arrived in Cairo in March, I got a ride home from the airport with two young Egyptian guys I’d met on the plane from Spain. They worked for Vodafone, Egypt’s most popular cell phone company, and carried shopping bags bursting with European chocolates and perfumes from the duty free store. We drove to my friends’ apartment in their Fiat, and as I gazed out the window and remarked at every old familiar landmark, we turned up 26th of July, passing the Date Market. The stalls were brightly lit with the neon green of Cairo mosques at night and the florescent bulbs that light the way for late-night shoppers.

“Wekalet Al-Balah!” I cried, and they dissolved into laughter.

“You know it?” one asked with surprise. I told them it was my favorite place in Cairo.

“Ok, yeah, it’s cheap,” conceded the other. “But we don’t go there.”

This attitude may be changing. Though Egypt is still a highly stratified society, people like to talk about how the revolution united the classes with a common cause. Whether or not this is true (my experience in Cairo is that not much about classism has changed), there’s one trend in Egypt that may serve as an even better — though bittersweet — unifier than the revolution itself, and that’s the post-revolution economic downturn.

Egyptians often divide time into abl as-soura (“before the revolution”) and baad as-soura (after the revolution). In Wekalet Al-Balah, I most often hear baad as-soura to refer to the alarming economic dive Egypt has experienced since ousting Mubarak, similar to the way we use the term “crisis” in the US.

Inflation and unemployment have gone up, the stock market value, wages, and foreign reserves have gone down, and tourists have gone home. Just like the economic crisis in the US, it’s as difficult to single out the causes as it is to sum up the effects of Egypt’s current troubles, but it’s safe to say more Egyptians than ever are feeling economic impacts and pressure.

Used clothing may never be dressed up as ‘vintage’ in Egypt the way it is in the West, but with the economy the way it has been since the revolution, more and more of the City Stars set might find themselves needing to turn to more affordable options, like the clothing at the Date Market.

Egypt’s economic downturn

The Mohameds say that in the days right after the revolution, business in the Date Market, like business in most of Cairo, was bad. Most shops were closed, and many people were afraid to leave their homes. One vendor told me that he’d been afraid to buy a large shipment of goods from Port Said because looting was rampant. These days, it’s clear from the shoppers jostling each other for space at the racks that business is better than business as usual.

But this doesn’t mean making a living here is easy. Vendors pay a commission to middlemen in Port Said to get them the higher-quality brand-name goods, and another to the bosses who own the actual storefronts in Bulaq, controlling the sidewalk and street space out front, which they rent to smaller-time sellers like the Mohameds, Hilali, and Hilal.

With all of this overhead, it’s sort of hard to believe anyone selling clothes for as little as 20 cents can turn a profit. One reason more and more vendors keep trying their luck at selling used clothes is that the alternatives in government re-settlements like En-Nahda are bleak.

“The people don’t find opportunities for making money there, and many of them end up selling drugs,” says Sayed.

But vendors choose the Date Market over alternatives, and not such bleak ones, that are right here in Cairo, too — Mohamed Kebir studied in the Faculty of Commerce at Ain Shams University, and Mohamed Sogayyar works construction during the week for Arab Contractors. They estimate they keep only 15 Egyptian pounds for every 100 pounds worth of clothing they sell at the Date Market.

Despite this, and the fact that Mohamed Sogayyar gets health insurance and regular employment through his construction job, he says he prefers to work at Wekalet Al-Balah. Here he can spend the day alongside his friends and family. Because the market never closes, he can come and go when he wants. I ask what happens to the clothes the vendors can’t sell.

“Mafeesh,” says one vendor. “There aren’t any we can’t sell. If they don’t sell for fifteen pounds, we move them to the five pound rack. If they don’t sell for five, we give them away for two!” he laughs. “Everything is sold.”

Because Date Market vendors don’t have to haggle, Mohamed doesn’t have to compromise with anybody. He can be his own boss. And even though they have to hustle to make a living here, many Egyptians have made it clear since the revolution that what they really want is to be their own bosses.

You can see this in the shop of a man named Said. Said has built his shop using the 6th of October Bridge — which was built in the 1980s to connect downtown and the upscale neighborhood of Zamalek, and which intended (and failed) to ‘modernize’ Bulaq — as a roof. The bridge covers the racks of used clothing he sells, giving him an improvised space for which he pays no rent.

The cave-like alcove at the end of the bridge where it meets the Nile is lit with bare light bulbs, and homeless old women in wheelchairs doze beyond his racks of clothing, barely visible under their dirty blankets.

Said, an older man with a close-cropped white beard and a plaid scarf wrapped turban-style around his head, perches on a railing. He checks his cell phone, which is dangling from a charger rigged up to an extension cord, every few seconds. A small boy, Moustafa, sits next to him, restlessly hopping on and off the railing and following our conversation with eager eyes.

“I’ve been selling at Wekalet Al-Balah for 25 years, probably as long as you’ve been alive,” says Said. “It’s not just random selling. When we get the clothes we have to sort them by shirts, pants, dresses, kid’s clothes, etc., but also by quality. You have to have an eye for how much you can get for each thing, and what someone will pay more for,” he explains with obvious pride for his work.

Moustafa is learning all of this. He’s only 11, about the age Nasser was when he first came to Bulaq to sell clothes on the sidewalk, but he left school to work at the Date Market.

“I’m a failure at school,” he says smugly. He has the perfectly coiffed hair and tucked in shirt of a salesman, but he’s young-looking for his age.

“Which is better, school or working here?” I ask.

“School’s better,” interjects his older cousin, who also sells clothes.

“No, working!” Moustafa insists, then dashes out to the sidewalk to call out the price of men’s jeans to a woman passing by.

“It’s true, he is already a good worker. See how loudly he shouts?” admits his cousin.

Said watches Moustafa, who has his hands cupped around his mouth to project his voice over the noise of competing hawkers, and nods in approval. He turns back to me and squints his eyes, thinking.

“Put it this way — just like women like working in the home, I love working in Wekalet Al-Balah,” he says, in an analogy which I’ll excuse. “It’s my place.”

Before leaving the Date Market for the day, I ask if I can take a picture of Moustafa and Said. As I fumble to get the lighting right in the shadows of Said’s shop, Moustafa asks Ahmed, “Why do foreigners always want to take pictures of everything?”

“If you went to America, wouldn’t you take pictures of everything?” explains Ahmed. Moustafa thought about it for a second, pouting his lips.

“Yes,” he says. “But if I went to America, I would make a lot of money — and I would bring it all back here to Bulaq!” he declares, then jumps down off the rail and runs out of sight. [Note: This story was produced by the Glimpse Correspondents Program, in which writers and photographers develop long-form narratives for Matador.]