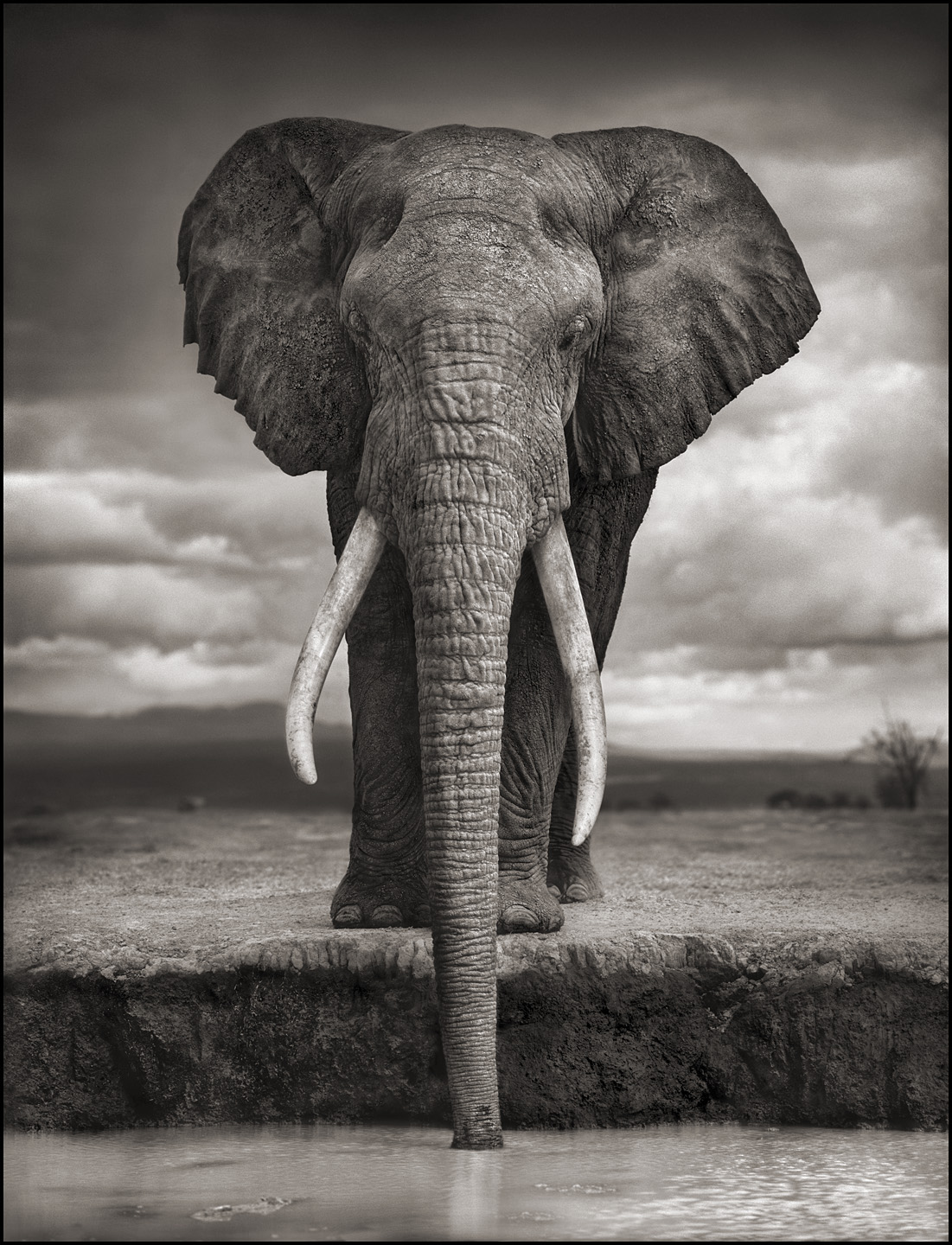

Take a look at the elephant in the photo below. His name is Igor (as named at birth by Cynthia Moss of Amboseli Elephant Research). For 49 years, he wandered the plains and woodlands of the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa. A gentle soul like most elephants, he was so relaxed that in 2007, he allowed me to come within a few feet of him to take his portrait.

Across the Ravaged Land

Two years later, in October 2009, it was perhaps this level of trust that allowed poachers to get close enough to kill him and hack the tusks from his face.

This book, Across the Ravaged Land, is the final book in the trilogy that I began in late 2000. Being something of a natural pessimist (always tempting to actually just say “realist”), I always felt that I was potentially making a final testament, an elegy, to the extraordinary natural world of East Africa, and the wild creatures that inhabited it. Back then, in my first book, On This Earth, I photographed what I saw as something of a paradise, an Eden. And it was, compared to what is happening today in 2013. But even 13 years ago, my pessimistic mind did not conceive that things would turn this bad, this quickly.

As I write, there is a continent-wide apocalypse of all animal life now occurring across Africa. When you fly over such a vast continent with so much wilderness, it’s hard to imagine that there’s not enough room for both animal and man. But between an insatiable demand for animal parts and natural resources from other countries, and a sky-rocketing human population, the animals are being relentlessly squeezed out and hunted down. There is no park or reserve big enough for the animals to live out their lives safely.

The statistics are finally, belatedly, starting to become known, and they need repeating:

Every year, an estimated 30-35,000 elephants are slaughtered across Africa. That’s 10% of the elephant population every year.

Fed by the massively increased demand from China and the Far East, ivory prices have soared from $200 a pound in 2004 to more than $2,000 a pound in 2013. China’s population is 1.3 billion and counting, and with 80% of its fast-growing middle class keen to buy ivory in some form, its price will only keep spiraling upwards. (It barely merits stating the obvious: Ivory is never more beautiful than when thrusting magnificently out of the face of an elephant).

As for rhino horn, it’s now more expensive than gold dust in the Far East, as the last rhino are gunned down to provide phony “medicine” for men with failed libidos.

There are an estimated 20,000 lions left in Africa today, a 75% drop in only 20 years. Most of this decline is due to conflict with the fast-growing human population. But increasingly, lions are killed for body parts like claws, bones, and teeth, again for the Asian market, now that tigers are too hard to procure. It has become so bad that there are next to no lions left outside the parks and reserves.

Viewing the steep downward slope on the graphs, it means this: At the current rate of slaughter, there will be no elephants, no lions, no cheetahs left in the vast expanse of the African continent within 15 years.

The only place you will be able to see them is in the sad, drab confines of zoos. Or in fenced areas that constitute barely more than a glorified zoo. Once again, man is on the path to systematically exterminating entire species of his fellow creatures in the natural world. Will humanity learn and change as a result? Based on history, the despairing answer is no.

It all sounds fairly bleak, and much of the future inevitably will be. But there is a “however…” There has to be a “however…”

But we have to be prepared and willing to engage in the most almighty fight for it….

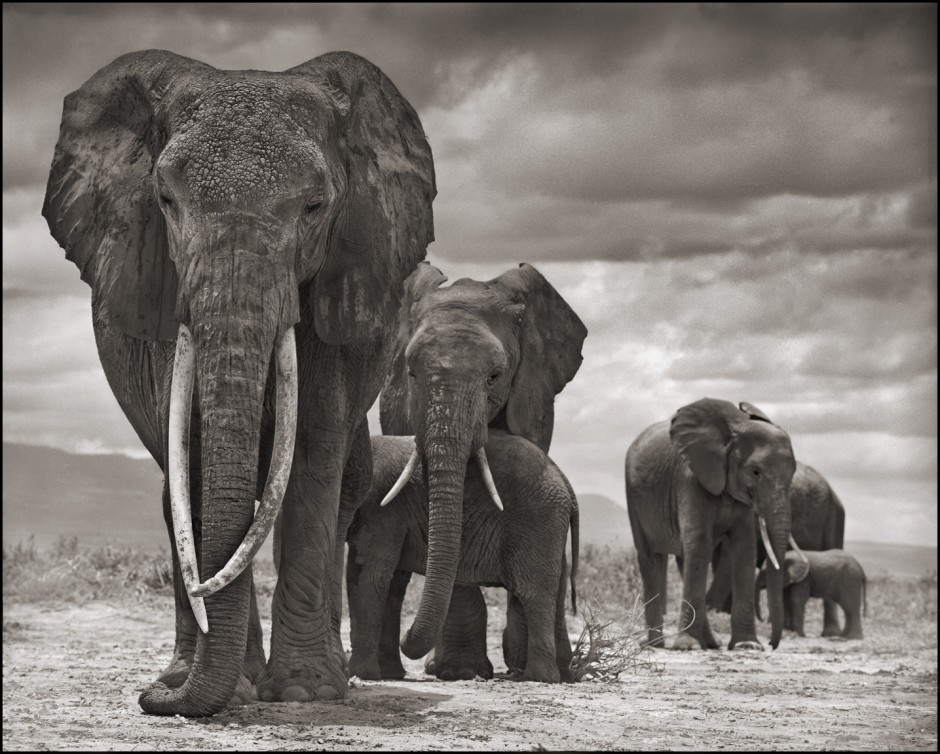

Whilst there in 2010, I learned about the killing the year before not only of Igor, but others as well, like Marianna, the matriarch purposefully leading her herd in the photograph below.

Day after day, we tried to approach what had once been some of the most relaxed of elephant herds, elephants that in the past had quietly made their daily journey to the swamps, moving past and around our vehicle without a care in the world. But this time, when we approached to within half a mile, they would run in terrified panic. Meanwhile, gunshots were being reported from the direction that the elephants came, near the Tanzanian border.

We tried reporting what we’d seen, but nothing was done, nothing happened. The Kenya Wildlife Service was (and still is) underfunded, and the few NGOs in the area had insufficient funds and infrastructure to make much of a difference. On the Tanzanian side, there was no one at all engaged in protection or conservation. And this was here in the Amboseli ecosystem, one of the most important and famous in Africa, with the most spectacular remaining population of elephants to be seen in East Africa.

Over the coming weeks, there was a lot of bad news. Just six weeks after I took the photo below of Winston, this 30-year-old elephant, barely into his prime, with half his life ahead of him, was shot by poachers over the border in Tanzania. Wounded, he made it back over to Kenya, where he died. He also had his tusks sawn out of his face with a power saw by the poachers. (And you won’t want to read this, but many are the elephants who are still alive when the chainsaw, or ax, starts hacking the ivory out of their faces).

Over the next couple of months, the roll call of big bull elephants killed by poachers came thick and fast: Goliath, Sheik Zahad, Keyhole, Magna, and more. It wasn’t just a case of if a big-tusked elephant was going to get killed, but when.

At first I thought the poachers would just target the elephants with big tusks. But elephants with tusks barely more than broken stumps were being killed by poachers. Which meant that really, no elephant was safe anymore.

The killing was also escalating for all the wild animals of the area. The plains animals were getting slaughtered; giraffes here in the region were being killed at a faster rate for bush meat; there were even contracts out on zebras, as their skins became the latest fad in Asia.

As I saw the destruction unfolding with almost no real or meaningful protection, I thought that I couldn’t just stay frustrated, depressed, and powerless. It’s no good being angry and passive. It’s much better to be angry and active.

And so, to my own complete surprise, I co-founded Big Life Foundation in late 2010, made possible by an incredibly generous donation from one of the best collectors of my photographs. Partnering with the highly regarded conservationist Richard Bonham, we set our sights on the Amboseli ecosystem as our pilot project: a nearly two million-acre area stretching across the Kenya/Tanzania border.

A little over two years later, Big Life has 280 rangers, 24 ranger outposts, 15 patrol vehicles, 2 planes for aerial monitoring, 3 tracker dogs, and a vast informer network across the whole region. It’s the only organization in East Africa with coordinated cross-border anti-poaching operations.

With this infrastructure in place, as of April 2013, the Big Life teams have achieved a dramatic reduction in poaching of all animals in the region. None of this could have happened without one critical element: With animals constantly moving far beyond park boundaries into unprotected areas ever more populated by humans, the only future for conservation of animals in the wild is working closely with local communities. Effective conservation is dead in the water without community collaboration. This is at the heart of Big Life’s philosophy. The people support conservation, conservation supports them.

Elephants Alone on Lake Bed

In parts of the world such as this, very poor but rich in natural wonders, ecotourism is the only truly significant source of long-term economic benefit. Take away the animals, and there’s almost nothing of economic value left. The land can only support so much herding, and even less farming. And those meager resources will only become more unsustainable and precarious over time, as climate change kicks in and brutal droughts occur more frequently.

When you’re trying to protect close to two million acres, with the best will in the world, 280 rangers and 15 vehicles are only going to get you so far. That’s where the support of the community is essential.

Big Life’s expansive network of community informers is one of the main reasons why the rangers now apprehend poachers most times that they kill. Every one of those rangers lives locally, and with families whose well-being is tied to their success, and the wealth of the region increasingly understood by local people to be tied to the health of the ecosystem, so each ranger has his own small network of eyes and ears. Given the size of the area, I find it quite amazing, and very encouraging, just how often information does come through to the teams about poachers operating in the area. And on the poacher grapevine, it is now known that you run a big risk of being arrested if you attempt to kill in the Big Life-protected areas.

But the aim of Big Life has always been to do much more than just catch poachers. Its aim is to protect the entire ecosystem, both in the short and long term. Loss of wildlife habitat, the expansion of human settlement due to population pressure, and the resultant animals killed during raids on farmers’ crops or in retaliation for attacks on livestock — all add to the toll of lost wildlife. And all, in one way or another, we attempt to address.

Meanwhile, however, the destruction of wildlife continues, escalating and out of control, in the areas beyond where the Big Life teams operate. This is why this year, 2013, we began to extend operations into the Tarangire/Manyara area of Northern Tanzania, where large numbers of animals, from giraffes to zebras, were being gunned down for the bush meat markets of Arusha and beyond.

However, I don’t want this to turn into an extended pitch for what Big Life Foundation is doing. If you’re interested, you can discover more at Big Life’s website. But if you’ve made it this far, perhaps that means you might join the fray.

Unfortunately, we’ve reached a point where a series of terrible choices have to be made: what we can still try and save, and what we have no choice but to painfully, reluctantly sacrifice.

All across the African continent, there are entire populations of elephants and other animals now being wiped out. The list is long: animal populations in Chad, Central African Republic, Mozambique, Congo, large parts of Tanzania, and on and on. Tragically for many of the ecosystems in these places, any conservation group would face an overwhelming struggle to be effective — for lack of government support or community collaboration, for lack of money, for lack of firepower against the rebel militia groups that sweep in to murder en masse, financing weapons purchases with their bloody bounties of ivory. In fact, as I’m writing this, I’ve just read a news report about 86 elephants killed in the last week in Chad, including 33 pregnant females. And no one there to stop it for all these exact reasons.

So until sufficient national and international pressure is exerted to implement truly meaningful bans on the worldwide trade in animal parts, we will have to continue to choose which battles we stand a chance of winning, and those we know we cannot.

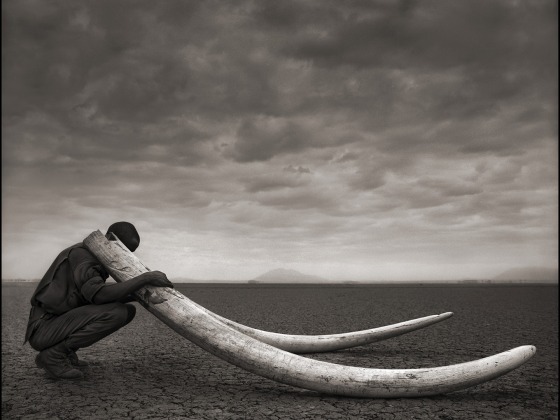

The photograph above shows 22 of the Big Life rangers holding tusks of elephants killed by men within the Amboseli/Tsavo Ecosystem in the years 2004-2009. The photo was taken to echo the earlier photograph, Elephants Walking Through Grass, reproduced further above.

Corporal Kitanki — at the front, and with one of the best track records of capturing poachers — is holding tusks that each weigh in excess of 120 pounds. These same tusks are supported on the shoulders of another Big Life ranger, Corporal Pepete, in the photograph on the cover of the book Across the Ravaged Land.

Those two gargantuan tusks, that bounty, would fetch close to half a million dollars in China today. However, as I look at those tusks in the photo today, I’m not thinking of that.

I’m looking at them thinking that actually, I find it hard to visualize the living elephant that possessed them. I’ve never seen elephants with tusks anything like that size, and now, I never will. They are all gone, dead, mostly killed by man. Even with one part of each tusk embedded in his skull, this elephant would still surely have had to lift his monumental head to prevent them from dragging like excavators through the earth.

On October 27 2012, I took the photo above, of Qumquat, one of Amboseli’s most famous matriarchs, and her family. Beyond are two of her daughters, Qantina and Quaye, bearing smaller tusks. You can see that I was just a few feet from the family, so trusting, so relaxed. Such easy pickings for poachers with a mind to murder for profit. Sure enough, this was to be their last afternoon alive.

Twenty-four hours after this photograph was taken, Qumquat, Qantina, and Quaye were gunned down by one of Amboseli’s most notorious poachers (whom the Big Life rangers subsequently apprehended). As for the three youngest, two are missing, the younger almost certainly dead now. Only the youngest calf is alive, his new home the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust Orphanage in Nairobi. This is the kind of collateral damage that the poachers cause: abandoned, traumatized calves that cannot survive once their mothers are gone.

Qumquat was a wonderful matriarch, who successfully led her herd for many years. But in one hellish afternoon, three generations of her family were exterminated.

Meanwhile, there are thousands of other Qumquats and sons and daughters still across much of Africa, many of whom will inevitably meet a similar fate. Whether this kind of senseless destruction motivates you to donate to Big Life, or another group working to protect the animals or environment here or elsewhere on the planet, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that, cliched as it sounds, if you care, get involved. Don’t be angry and passive. Be angry and active.

This book marks the end of a trilogy — On This Earth, A Shadow Falls, Across the Ravaged Land — that began in paradise, and ends in a much more somber place. I took portraits of the animals in these books in an attempt to capture them as sentient creatures not so different from us. I have sought to photograph them not in action, but simply in a state of being. Let us continue to let them be.

This post was originally published at NickBrandt.com and is reprinted here with permission. It was originally posted on Matador on October 30, 2013.