After years of tortuous negotiations, a global treaty to halt climate change may, just may, be in sight.

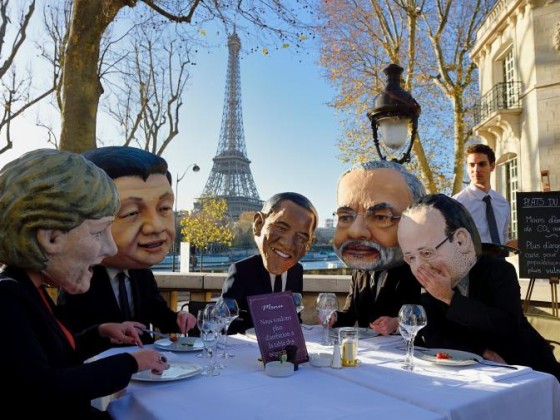

World leaders and more than 40,000 delegates from 195 countries will descend on Paris for the United Nations climate summit from November 30 to December 11 with the aim of finalizing and then inking the historic deal.

But even with the mega-talks about to kick off, there remains a huge amount of work to be done to hammer out the nitty-gritty of who will cut their carbon emissions by how much, and who will pay for what.

Here are the key facts about the Paris negotiations and how they could decide the future of planet Earth.