IT WAS an exhilarating time to be young in November 1989 and living in East Berlin. It was not only the physical Wall that fell on November 9. It was also the many invisible walls that closed off anyone who didn’t conform. All those who had been largely hidden from sight – punk rockers, dissidents, transvestites – stepped out of the closet, so to speak, and into a newly liberated public realm.

Squatting East Berlin in the '90S

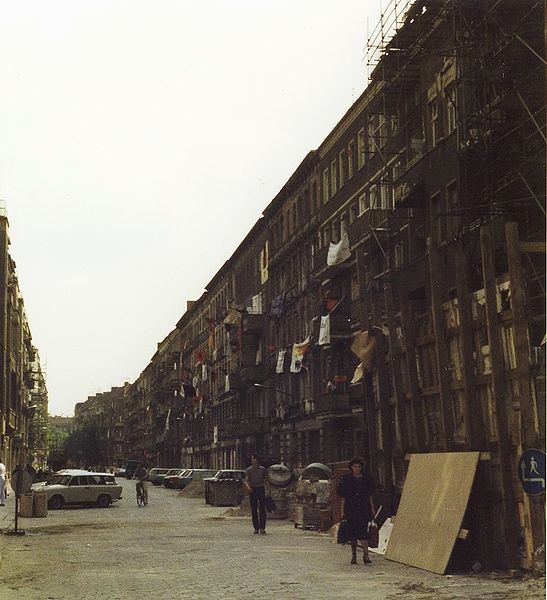

Many East Germans had already fled the country in 1989 before the Wall fell – decamping to Prague or travelling through Hungary to Austria and West Germany – and many more streamed across when the border opened. They left behind their jobs, their Trabants, and, perhaps most importantly, their apartments. For those who stayed behind, especially young people, there were suddenly a huge number of empty places they could occupy. The big cities in East Germany, but particularly East Berlin, became squatters’ paradise. Even people from West Berlin, which had its own squat culture before the Wall fell, began moving East – to the new land of squat opportunity.

As a young man, Dirk Moldt was involved in the opposition movement in East Germany, particularly the Church from Below group that broke away from the official Church structures. He was also at the center of the squatter culture that blossomed in East Berlin in the early 1990s. Back in February, in a café in what had once been a primary squat neighborhood in East Berlin, he told me about the party atmosphere that prevailed in those early days after the Wall fell.

“On Mainzer Straße, there were 11 buildings squatted,” he related. “Visually and culturally this was something new. The part of the street with squatted houses was 200 meters long. On the street there were several different groups. One house, for instance, had transvestites. The boys walked around with very hot female clothes. It looked like in a movie. They were wearing make-up and blonde little curls and short skirts, it looked really crazy. Other houses were really militant where they were always wearing black clothes and hooded jackets. All the houses were draped with flags and banners. Every evening, people would sit in front of their houses eating, chatting, and drinking.”

But the squats occupied only one side of the street. “On the other side of the street, normal people were living,” he continued. “The problem was that they had to get up early to go to work. Most of them didn’t dare tell the squatters to please be quiet. If they called the police, the police said: ‘We are not stupid, we are not going in there.’ A street where the police doesn’t go? No state can tolerate this.”

The state struck back. So did the neo-Nazis. Eventually the forces of gentrification also ate away at the squat culture. Dirk Moldt still lives in the apartment that he squatted so many years ago. Over coffee, he remembered the intense joy of those early days as well the intense despair that followed, particularly when neo-Nazis killed one of his close friends. The interview was conducted on February 6, 2013 in Berlin. Interpreter: Sarah Bohm.

DM: I was born in Pankow, a district of East Berlin in 1963. I have had several professions. I am a trained watchmaker. I worked for the Volkssolidarität (People’s Solidarity) – a social organization in the GDR, which was supporting old people. I also worked as a librarian, and in 1996 I started to study at university. I studied medieval history until 2002. From 2004 to 2007 I did my Ph.D. Now I work as a historian and sociologist in different areas. It’s difficult to find a job. Hence I do not have a permanent job.

Do you remember where you were and what you were doing when you heard about the fall of the Wall?

I overslept the evening of the fall of the Wall. I worked very hard on November 9. I was very tired, and we had an appointment with friends. We wanted to meet, but they didn’t come, so I went to sleep early. The next morning I heard that the Wall was open.

What was your feeling when you heard about it?

For me and also for my friends, those weeks were an endless party. I grew up in social circumstances that were as rigid as concrete. But since about mid-September 1989, things slowly started to change. Then in the beginning of October, let’s say October 7 and 8, there was so much change every day like never before in my life. The opening of the Wall was a new dimension on top of that.

I worked in the Kirche von Unten, the Church from Below, a resistance group here in Berlin. In the middle of the 1980s, the leadership of the Protestant Churches in the GDR did some things that seemed very close to the state.

Thus, many groups within the Church that were critical formed the Church from Below. Actually, we never believed that there would be a change, only that there would be some small relief. Such a great change was totally unimaginable. That’s the reason why the joy about the opening of the Wall was so big.

There was also another aspect. We always knew that the existence of the GDR was closely linked to the Wall. The Wall basically protected the system and the state. So, our feeling was ambivalent. We were very happy. At the same we realized – subconsciously even though it was obvious at the time — that if the Wall is open, the GDR will stop existing. We wanted change within the GDR. But we also wanted the state – this country – to continue to exist.

There was a particular reason. We were younger. We grew up in the GDR. The existence of the state was normal to us. Our conception is maybe comparable to the existence of Germans in Austria or in the Netherlands or in Belgium or in Switzerland. Everywhere in those countries there are Germans. In the same way, the GDR was a German state. We couldn’t imagine that there would be such a big change in Europe like we’re having nowadays.

And this might sound a bit strange. To us, cities like Hamburg or Munich or other West German cities were much further away than, for example, Krakow or Prague or Budapest. That was the perspective from behind the Wall.

So, you had a party for two weeks, or three weeks…

Oh no, for three months! We had a feeling of elation. For example, every day you encountered boundaries. There was the Wall. But there were also invisible boundaries. And there were a lot of functionaries and police. There were also normal citizens who always said: “It has always been like that and it is good like that and what you do is wrong and so on.” To see that they didn’t understand the world at this moment when their “idyllic world” was falling apart was also a party.

I understand that you were part of a squat here in Berlin.

All my friends lived in squatted flats. The principle of a squat was not new to us. Here, in Friedrichshain, it’s now an area where a well-situated middle class lives. But in the early 1980s it was a proletarian environment. Many flats here were in very bad condition. They had stoves, but only very few had radiators. There were few bathrooms. Toilets were outside the flat on the stairway. And a lot of flats were empty.

We squatted these flats. We had a special system for doing this. It was not allowed but you could nevertheless do it. Of course we listened to radio, to Free Berlin Broadcasting (SFB) and Radio in the American Sector (RIAS), these Western radio broadcasts. In the early 1980s, there were daily reports on SFB about squatted houses in West Berlin. Sometimes we were better informed than the people in the West. Of course the circumstances of these squats were different. We knew that.

In 1989, when the Communist government was no longer in power, my friends and I said: “We are going to squat a house. It does not belong to anyone and we would like the house for us.” It’s here on the street called Schreinerstraße. This happened in December 1989. To us, this squat was not something new but a normal consequence of the revolution. We also viewed the squat on Mainzer Straße in that way. In West Berlin we met old and new friends and told them: “In the East there are a lot of empty buildings. You can support us by squatting buildings.” And then people from Kreuzberg and also from West Germany came and squatted houses.

How long did the house squat last?

We squatted the house until 1997. Then we got contracts. I am still living there.

How many apartments was it?

We had 20-25.

Was there a kind of community organization? Or did people just live in their apartments and that was it?

In our house, we’d known each other for many years as friends. We already had a social structure. We also had more experience than younger squatters. We had more experience of life. For example, we had a principle that every adult had to have his own room, to be able to close the door behind him. This is very important. Many teams of squatters broke up later because of this. Because of normal life issues like: who does the dishes and who takes out the trash? We already had experience in fighting over this.

Once we had some visitors from Copenhagen. These Danish squatters gave us a poster of a huge pile of dishes. Below the picture were the words: “First the dishes then the revolution.” And also: “Believe in yourself.” So, the problem is the same everywhere.

Was there one kitchen for all the apartments?

We had one kitchen for several people. And we had apartments with a kitchen for a single person.

How would you say that the squat here was different from a squat, say, in Kreuzberg in West Berlin?

It was totally new here in East Berlin. From 1989 until 1991/1992, everything that happened in East Berlin was totally new: new structures, new laws, new governments in the city, a new party system. That’s why people just accepted it somehow. Normally, citizens in the East are less tolerant than those in the West. This is because of the education in the GDR. Only a few were open to tolerating different opinions, for example.

Also, the structures in East Germany were not as fixed as in West Berlin. In West Berlin, every building had its owner. In the East many buildings did not have an owner. They’d been managed by the state, so you did not know the owners. Then the residential companies and also the district administrations said, “Those who want to live here, should come.” This was because so many flats were empty. In the beginning it was tolerated. Some people wanted to have a contract, and we were suspicious of them. A squatted building was something different than a single tenant saying: “I want to live here, and I want a contract.”

The squatters from the West were different from the squatters here. They’d been brought up differently. They had different ideas about politics and squatting than we had. For instance, we’d internalized the idea that we could not change anything anyway and we should first negotiate and get along with each other somehow.

We were not focused so much on confrontation like the squatters from the West. We also said that living in the squat concerns the whole personality. It wasn’t just political. Therefore we had a different connection to the building than many squatters from the West. Of course, there were some house fighters in the East who wore blinkers, and there were some very smart squatters in the West. So, it’s not so easy to divide people strictly.

It also has something to do with the experiences. We had made different experiences than the young people in the West. In East Germany there was something called the Gesamtberliner Häusergremium (the Committee on Buildings for the Entire City of Berlin). As a representative of all squatted buildings, it tried to get general political acceptance from the political leadership and also a way to obtain contracts. But they did not succeed.

In the meantime the situation in the Mainzer Straße squat escalated. After the eviction from Mainzer Straße, the situation was totally different.

What did you mean by escalate?

On Mainzer Straße, there were 11 buildings squatted. Visually and culturally this was something new. The part of the street with squatted houses was 200 meters long. On the street there were several different groups. One house, for instance, had transvestites. The boys walked around with very hot female clothes. It looked like in a movie. They were wearing make-up and blonde little curls and short skirts, it looked really crazy. Other houses were really militant where they were always wearing black clothes and hooded jackets.

All the houses were draped with flags and banners. Every evening, people would sit in front of their houses eating, chatting, and drinking. On the other side of the street, normal people were living. The problem was that they had to get up early to go to work. Most of them didn’t dare tell the squatters to please be quiet. If they called the police, the police said: “We are not stupid, we are not going in there.” A street where the police doesn’t go? No state can tolerate this.

Then there was the escalation. It started with the eviction of a squatted house in Lichtenberg, and there was a demonstration in Mainzer Straße. A radical group of squatters from Mainzer Straße blocked Frankfurter Allee. The police tried to remove the barricade, and there was a confrontation. This escalated for three or four days. After that, Mainzer Straße was evicted.

Mainzer Straße was also a place of culture and creativity. It was the only colorful street in the whole district. Today Friedrichshain is said to be the creative district. But in 1990 the creative potential was evicted.

Where did those people go?

One part went to other buildings. One part went back to their parents. Some students, for example, moved to dormitories. There were some 100 squatters. But such a giant city assimilates them.

For your squat, was there a big difference between October 1 and October 3, 1990, before and after reunification? Did that make any difference on a day-to-day level in your squat?

For us, everything changed. We believed that there was a third way, a socialist way but without rules and ideological constraints, a bit like an anarchistic society. In January 1990, there was the first demonstration for reunification in Leipzig. I can remember that we laughed and said: “They are nuts.”The opposition in the GDR was only a minimal part of the society, maybe a thousandth or a hundred thousandth. Until October 1989 nobody in this opposition ever thought that the two German states could reunite.

A small part of the opposition – for example, Rainer Eppelmann, who lived and worked here around the corner – made a political turn in December 1989. Then they said: “We now want the reunification of the two German states.”

We believed that this was only a splinter of a splinter and that they wouldn’t have any success. But a lot of other people thought differently. Or they believed they would get a better life if they got the other society. For example people were also listening to Western radio and watching Western TV, and there was also this election campaign. We were totally surprised when we heard that most people were in favor of reunification. It wasn’t just us. Others, too, were surprised. Today I can explain this, but at that time I was totally surprised.

The elections were in March 1990. We believed that it would take two or three or four years until there could possibly be reunification. But that it only took one year was incredible. And the Volkskammer, the East German parliament, also worked towards this very fast. They said: “These election results can mean only thing about the future, which is reunification.” On July 1, the Western money came, with the Social and Economic Union. And then in October there was the Political Union. From the elections in March until October 03, 1990, I always feared that there would be a coup d’état, like what happened in Moscow. I thought that the generals of the Stasi or the National People’s Army would revolt. But they did not. They turned, too.

Did you try to continue that belief in the GDR in your small community? In your squatted house?

Absolutely not. It was a reality, and it was nonsense to foster something like Ostalgie. We always tried to be realistic. There was no space for something like that. But we were very frustrated. I have to admit this: we were really, really angry. For me, the years from 1990 until 1995/1996 were very very hard years. It was like a darkness to me. Not just because of the GDR but also because of the many changes. For example there was a very strong neo-Nazi movement, due to the intolerance among the population. Silvio Meier, the friend with whom I chose the building here, was killed by neo-Nazis in 1992. And there was no evening when you could go out on the streets without being afraid. That was how it was for me. I also had a family. So there were also good moments: when my son was born.

In the 1980s and also later, we believed that if the two German states would reunite we would have a very strong nation state and this nation state would raise questions about borders: “What about Pomerania, what about Silesia?” And this would have meant war. Many thought this way also in the West because it had already happened two times in German history. The Two-Plus-four Treaty prevented this. But it was not clear if this would be sufficient because of the problems we had with neo-Nazis.

In 1991, the King of Prussia, Friedrich II, arrived here to be buried in Potsdam. He had been buried somewhere else before. Helmut Kohl went to the funeral, and it was a state funeral. The Federal Army was also there with helmets and torches. This picture was very impressive. Friedrich II was one of the most aggressive kings in the history of Prussia. Of course, he also was a philosopher of the Enlightenment and did a lot of good things. But we saw this other side. And we really thought that after a few years we would have a war. Fortunately it did not happen. We then also saw that this Western democratic system had some good sides, that it was sufficient.

I started studying at the university. I also said goodbye to many old ideas, for example this idea that enterprises should be state-owned. I don’t have socialist ideals anymore concerning this issue. But I think that people should be able to decide on their personal issues. It’s still important to me that they have more self-determination.

We experienced the reunification like some kind of occupation. Many people, many leaders, came from the West into the East. They occupied leading posts at universities, school, and enterprises. My reflections changed when the war in Yugoslavia started. This was because the people leading the war used to be socialists. They were reformed socialists. Actually they exchanged the term “socialism” with nationalism.

There were a lot of those guys in East Germany. Also the politicians in East Germany were like this. Even after the fall of the Wall, this was their mentality. This was the first time when I was glad about the occupation. I thought, “This is better than war.” This was 20 years ago. Nowadays the system is stable.

But of course there are still many things that ought to be changed, that should become better. Here in this area the rent is steadily increasing. A twofold change of population happened here: a twofold gentrification. In the beginning, proletarians were living here. Everything that wasn’t nailed down was stolen.

If you walked down the street in the evening and saw somebody you didn’t know, you crossed to the other side of the street. In the 1980s and in the beginning of the 1990s, punks and freaks and hippies — the colorful people — moved here.

And nowadays, the upper income groups are moving here, and it has become a sleepy city. In our building we have fixed rent conditions, so our rent won’t increase. When we were squatters, we got those contracts. We’re in a cooperative, and this is relatively good. I only pay a little money. So it’s good to squat houses!

Now probably it’s not easy to squat a building in the city.

It’s almost impossible. You almost can’t do it. Of course you can’t say to people who are now living here and complaining about the rent: “You could have squatted a building.”

Would you be willing to talk a little bit more about your friend who was killed and the circumstances around that?

Silvio Meier came to Berlin in 1986, and that’s when I met him here. He was also there when the Church from Below was founded. Silvio and me, we were the treasurers. Even resistance has to be financed, and we were responsible for that. In 1989, we squatted in the house here.

Silvio organized together with me a concert in the church Zionskirche in October 1987. It was very famous: with the West Berlin band Element of Crime and also one band from the GDR. At the end of the concert approximately 30 skinheads attacked. Within the GDR, this case triggered a big anxiety. The police were also there but did not react. Some people who were injured went to the police and said: “They’re Nazis, do something!” But the police said: “No, we are not going to do anything.” After that we organized a press campaign together with our friends in the East Berlin Umweltbibliothek, an environmental library and an important opposition group, and his connections to West Berlin. We reported that there was a concert and that the Volkspolizei, which is officially antifascist, did not do anything when the Nazis came.

This press campaign contributed to a change in paradigm. Until then, the GDR was considered to be an antifascist state and Nazism was considered eradicated. There were no Nazis. And if there were some, it was due to the influence of the West.

Then the security forces, including the Party, the Stasi, and police, realized that there was an original problem with Nazis in the GDR. Groups of Nazis had regenerated themselves. It was a very strong problem not only in Berlin but most especially in the rural areas and smaller towns in the GDR.

The problem was that the young people were extremely frustrated and they had no political education. They just rejected the state ideology. The principle of intolerance that I was talking about earlier is also a result of this. It’s the reason why the danger from Nazis is still higher in the East than in the West.

You can say that what happened to Silvio in 1992 was: wrong time, wrong place. It happened at the metro station Samariterstraße. Silvio and three or four other people wanted to go to a party when a group of young Nazis came up to them. They were maybe 16 or 17 years old. They were wearing patches: “I am proud to be a German.” Silvio and the others asked the Nazis, “What are you wearing, what’s that about?”

Then the groups separated, and Silvio’s group went down to the station. They saw that there wouldn’t be a train, so they went back up again to take a taxi. The other group waited upstairs. They had butterfly knives, which were popular back then. With these knives they attacked the group. Silvio died and two others were seriously wounded. The young Nazis were given juvenile sentences, since they weren’t adults. First the police and then also the politicians said: “This is like a brawl in a pub. It has nothing to do with politics.” We made a press campaign and refuted this in public.

Last fall it was exactly 20 years ago. Nowadays there is a new anti-fascist movement with an initiative to name a street after Silvio Meier. They see Silvio Meier as somebody who fought against the Nazis. But we say, “Wait a moment, he did a lot more than that.” He was engaged in the movement for peace and the environment, he was part of the Church from Below. Not just the antifascist should be honored but the whole person.

One of the problems is that the Linkspartei, the successor of the Communist party, says: “Yes, Silvio Meier is an antifascist so this is really okay.” But politically Silvio Meier was totally different than this party. They want to construct a hero. This is one of the reasons why I don’t want the street named after him. There are also other reasons. We also had disputes. He was no hero but a very normal person. I always ask myself, “Why do we need heroes? Why do we have to do this?” I also say, “If you need heroes, you have to become heroes yourselves.”

They don’t understand this. They feel offended. These nice antifascists see the hero, a whole other person than he actually was during his life. But it is already decided that a street shall be named after him.

Which street?

Gabelsberger Straße. Just down at the metro station. I think Gabelsberger sounds better. But we then realized that we can’t prevent this process. So, what we did is that we have determined what will be on the plaque that will also be there.

Then you can have a more detailed explanation of his life.

It is a bit difficult on such a small plaque.

When I was here in March 1990, I was walking down Oranienburger Straße and I discovered Tacheles. No one told me about it, I just saw it and I couldn’t believe it, it was huge. And I walked there today and it’s all shut down of course, and everybody’s been evicted. I’m curious what you thought about that when it started and what you thought about it later when it continued.

I had quite a positive opinion of that during the whole time. The first squatters were friends of mine. Those artists didn’t really know how to squat such a big place. They asked friends of mine from the Bucket, who had already done it, how to do the squat.

There was this house of culture on Rosenthaler Straße that was squatted, and it was called Bucket. Some people said: “Today there’s no room at your place, so we’re going to Oranienburger Straße to squat this building and it will be Tacheles.” This is what one of the squatters there told me.

It was really okay for us. Every building that is empty should be squatted. That’s what buildings are there for. I am thinking about studios for artist. They are becoming more and more expensive. They have to work somewhere. If there’s an empty place they should go there and do it from my point of view.

In every history of a squatted house, there are cycles. There will be a climax with a lot of activities and there will be a recession, when everything is down, and it has been like that with Tacheles. Every avant-garde has its Hängefraktion, a group of losers who are just hanging around. Sometimes they’re the ones on top, sometimes the others.

Unfortunately the people from Tacheles did not succeed in getting better contracts during the time when the active people were on top. It’s a shame that it does not exist anymore. They made a lot of concessions. At some points they should have been more confrontational, and they should have worked more with publicity. I was sorry to see it all closed up like that.

Looking back to 1989 and everything that has changed or not changed today, how would you evaluate that on a scale of 1 to 10 with 1 being least satisfying and 10 being most satisfying.

Difficult to tell. When I have an optimistic day I would say 8. When I have a pessimistic day I would say 2

That means 5.

Okay: because I have studied and I have developed myself. But it’s not possible for me to find a good job. Because I am too old. I was older than the other students at university by more than 15 years. When employers see my birthday, they say, “Too old.”

We were born in the same year. So yes, I know the problem.

A lot of people our age in the GDR developed in a normal way. They studied when they were in their twenties and in West Berlin too. But I made the revolution. So I have to pay for this now. Not only me but also my son, because we cannot have nice holidays like other normal earning peoples, for example, or visiting concerts. There’s not enough money at home. So my son pays for the revolution too. This is a reason why I say 2. But the possibility that my son can say: Maybe I will go to the Netherlands for my studies. That wasn’t possible in the GDR. So, that makes me feel like saying 8 or 10.

You actually answered the second question, which was about you personally. The first question was looking at society in general and the changes in Germany overall on a scale of 1 to 10. Would you give it the same number? Would you give it a 5?

If I don’t play a role in this question, I would say maybe 8.

When you look into the near future two or three years and you evaluate the prospects for Germany on a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being most pessimistic and 10 being most optimistic.

Oh, I’m really optimistic. We live like on an island here. Germany is rich, Europe is rich, all the people want to go to Europe, want to get all the opportunities. You know this from the United States. But in 100 years it won’t so good if we have no change in our system.

It sounds like a 9, if I had to give you a number.

Okay. You think so, too? Would you say 9?

If someone asked me about the United States I’d be pessimistic. But I’m optimistic about Germany.

![Dirk Moldt [facing camera] reminiscing in his kitchen.](https://d36tnp772eyphs.cloudfront.net/blogs/1/2013/06/Berlin-Germany-moldt_fotos_ansehen21-e1370517840284-480x360-Matador-SEO.jpg)