LUIS, a man in his 30s, or maybe early 40s, owns a car repair shop on the Santiago-center street of 10 de Julio. Today’s march for education passed right outside his door, and rather than holing up inside, opening just a small keyhole to talk to people, or boarding up his place, he stood with the metal curtain raised. What’s more, he had the hose on, and there was an orderly line of about 15 teen-aged protesters taking turns to drink from it.

“Is this your store?” I asked.

“Yes, it is,” He said.

“And why do you have the hose on?”

“It’s going to be 24 degrees out today. They need water.”

He’s right, it’s uncharacteristically hot for this time of year (75F, and it’s the middle of winter), and as we rounded Parque O’Higgins, a group of kids went off to run through the water of the fountain that is on the corner to cool off. It’s easy to forget, if you watch the news, full of images of hooded vandals with their faces covered, throwing rocks and setting fires, that the protests are mostly peaceful, and largely populated by children. Today’s protests are part of a series of events seeking educational reform in Chile, and after last Thursday’s quashed attempts at an unpermitted march, this one is legal. And very well-attended.

The march started today down past Estación Central, in front of USACH, or the Universidad de Santiago, Chile. It was the usual array of clever-signed marchers, with students protesting in earnest, though some of their chants insult President Sebastian Piñera in no uncertain terms, using a common insult regarding his mother’s genitalia. There are other chants, as well, such as “Piñera, entiende, la educación chilena no se vende, se defiende ((President) Piñera, understand, education’s not for sale, we defend it!) and another crowd favorite “y va a caer, y va a caer, la educación de Pinochet” (And it will fall, and it will fall, the education (created by) Pinochet).

Today’s march took place in “Santiago Centro” but in a part which is south west of what is considered to be downtown. It was up the Alameda, and then south on Avenida España, where many universities are located, near one of the two large urban parks (where the kids jumped in the fountain), and past car parts stores (like that of Luis, with the hose). They held banners proclaiming “we want education, not repression,” had built a giant pretend megaphone out of paper and pvc tubing, which said, “will they listen to us?” on the side, and I even ran into one guy who had a machine gun fashioned out of green balloons, the kind normally twisted by a clown into the shape of a dog. Felipe, who was carrying the gun, told me that he and all of his friends at the Universidad de Chile Geology department had figured out how to make them watching it on YouTube. It’s a joke, he said. There are the police, all serious and uniformed, and we’ve got pretend guns pointed at them.

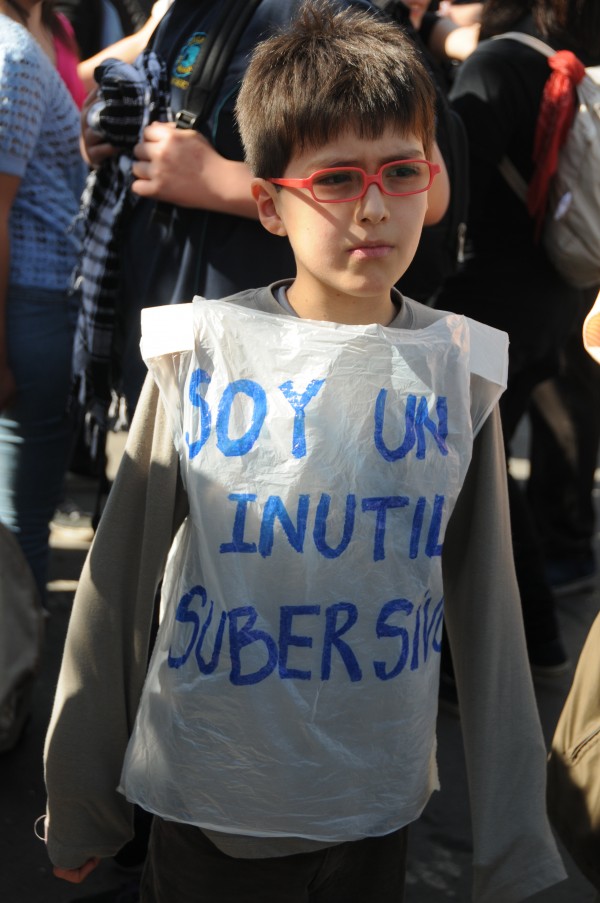

After marching a couple of kilometers, we all later spilled into the planned end of the march, at Parque Almagro, where peaceful chanting and milling took place, and I talked to a bunch of parents who’d brought their kids along, including Susana, whose 9-year-old son had insisted on wearing a slogan. They chose “soy un inutil subersivo,” (sic), which he sports in the photo below. The translation is, “I am a useless subversive,” taken from a speech recently made by Senator Carlos Larraín in which he said “we’re not going to let a bunch of useless subversives force our hand” (referring to the education protests). I left them my card after taking his picture, choosing the one that had a photo of graffiti that says “capitalism is death” on the flip side, because I knew the kid would like it.

I left the park around 1 PM, after a family living in a cité (a narrow alley of homes that face each other) refilled my water bottle from their kitchen sink. I was tipped off by some low-tech gossip (I overheard it), that Paseo Bulnes (a nearby street) was burning. And it was. It’s a pedestrian street, and at Eleuterio Ramirez, some “encapuchados” (hooded protesters, their faces are hidden) had set a bonfire out of construction debris, and taken down the street signs. A fight was taking place between the riot police (tear gas and water cannons), and the hooded participants (rocks). Rocks went one way, and gas canisters whizzed the next. This is where I discovered that even with a respirator and eye protection, you don’t want to be so close to the projectile (gas canister), that you can see it sparking, hear it clink dully to the ground, or feel its heat. I guided my bike to a place out of the way, where I pulled off all my protective gear, and spat and blew my nose. After the burning subsided, I doubled back to see if the crowds were still there, and they were, though they were definitely in motion.

Watching the fracas, there was a young girl, maybe fifteen, in a navy hooded sweatshirt with a plaid shirt underneath. She had an asymmetrical haircut, part crew cut, part long, leaning against a wall. She was rubbing the crewcut part, and I asked her what had happened. “A rock fell on me,” she said (the implication being not that it was thrown at her, but that she’d gotten hit by accident). Why don’t you move away from here, I asked? And she rubbed her head some more, and shrugged.

Though the protests were largely peaceful, images on the local news show rocks, teargas and violence. And the students know this will be the case. As they passed one of the television stations (Canal 13) filming from atop the fence that surrounds Club Hípico (a racetrack), they chanted “Prensa, burguesa, no nos interesa” (We don’t care about the bourgeois press).

But what about the independent press? Radio BioBio, an independent radio station, reported that at least one of the encapuchados in the port town of Valparaíso, (where there are also protests), had run up to a gate surrounding the congressional building, and had been let inside, by the police, which led to accusations (not the first time) that infiltrated police are among the encapuchados, embedded within them to incite violence and make the protesters look bad. A YouTube video (in Spanish) shows senators and other people who work at the Congress explaining what they saw and demanding an explanation, which was not forthcoming.

During the course of the protests, I was taking photos of a lineup of police in riot gear set up to keep the march on course, crossing Avenida Matta. A middle-aged woman yelled at me. “No les saques fotos a los carabineros, sácales fotos a los delincuentes.” (Don’t take pictures of the police, take pictures of the delinquents). On days like today I feel like I might not be qualified to make that call.