In 1933, eighteen-year-old Patrick Leigh Fermor faced an uncertain future. His school career had been riotous but undecorated. His wild temperament was, in his own words, ‘unfitted for the faintest shadow of constraint.’ Fellow schoolboys adored him for his antics, but his teachers demurred: in one prescient school report, a long-suffering housemaster described him as ‘a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness.’ All this drove his parents to despair. What on earth was the boy to do? Seek entry to a second-rate university? Apply for Sandhurst and join the army? Neither of these well-worn paths seemed suited to his personality.

The Lost Art of Reckless Travel

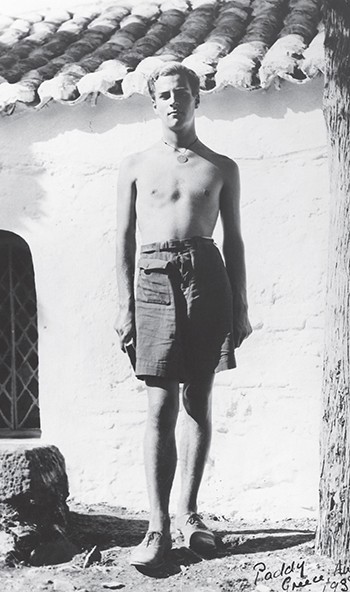

Instead, Leigh Fermor — known to his friends as Paddy — tossed aside his respectable options, and jumped aboard a Dutch steamer bound for the Continent. Armed with a battered rucksack given to him by Mark Ogilvie-Grant, a friend of the travel writer Robert Byron — and with no possessions but a few clothes, a solid pair of boots, a book of English verse, and his beloved Loeb edition of Horace’s Odes — Leigh Fermor set out to walk overland from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople. The journey, later recorded in A Time of Gifts, would take him through the troubled Germany of a newly ascendant Hitler; along the banks of the then-untamed Danube; through the former lands of the splintered Austro-Hungarian Empire; and into the heart of the Balkans. (Tragically, much of what he saw along the way — and many of the people he met — would disappear forever after war broke out five years later).

No guidebook existed to help him plan his route. Ancient maps showed the proximity of one town to another, and helpful villagers pointed him in the right direction, but Leigh Fermor relied mainly on his instincts and his romantic imagination to guide him. He was lured from place to place by little more than an evocative name — Bohemia! Transylvania! the Iron Gates! — and, by giving free reign to his historical curiosity and his literary bent, he travelled through time and thought as well as space. He slept in hayricks and castles, played bicycle polo with Hungarian aristocrats, and excitedly discussed passages from the Torah with Orthodox Jews in a remote Carpathian lumberyard. Sleeping under the stars beside a river one night, he was rudely awakened by two policemen, who arrested him as a smuggler and then released him upon learning that he was a mere errant student. Trudging along country roads at dawn or dusk, he would sing pop and folk songs of the day or recite Latin poetry. According to his own account:

. . . [Songs] sung as I moved along, evoked nothing but tolerant smiles. But verse was different. Murmuring on the highway caused raised eyebrows and a look of anxious pity. Passages, uttered with gestures and sometimes quite loud, provoked, if one was caught in the act, stares of alarm. . . . When this happened I would try to taper off in a cough or weave the words into a tuneless hum and reduce all gestures to a feint at hair-tidying.

Everything Leigh Fermor encountered on his path was tinged with romanticism, be it town, river, forest, or fellow peripatetic. An itinerant chimney sweep he meets ‘on the road between Ulm and Augsburg’ seems intoxicated by the same wanderlust:

While [the chimney sweep] explained that he was heading south to Innsbruck and the Brenner and then down into Italy, he unfolded his map on the table and his finger traced Bolzano, Trento, the Adige . . . and as he uttered the glorious names, he waved his hand in the air as though Italy lay all about us. . . . Warmed by another schnapps or two, we helped each other on with our burdens and he set off for the Tyrol and Rome and the land where the lemon trees bloomed (Dahin!) and waved his top hat as he grew fainter through the snowfall. We both shouted godspeed against the noise of the wind and . . . I plodded on, eyelashes clogged with flakes, towards Bavaria and Constantinople.

It was after reading this anecdote in my Munich dormitory that I became infected by the spirit of Leigh Fermor’s narrative, and made a quixotic decision to walk across the Alps myself. Before setting out from Garmisch-Partenkirchen, in southern Bavaria, I purchased a small flask of German whiskey, for no other reason than I liked the idea of ‘warming myself up’ with it when soaked by the inevitable cold rains of the Brenner. I took shelter at a biathlete’s house in Mittenwald, met a pseudo-Conchita in Innsbruck, and stumbled onwards through Matrei am Brenner before finally reaching Vipiteno in northern Italy.

My efforts turned out to be rather ridiculous. Snow still covered the mountain paths, so I had to follow the highways. In my mind, I caught glimpses of Roman legions and World War Two troop movements (the Brenner has a long history as a major Alpine pass); but in reality, convoys of Schengen-era freight trucks roared past me, sleet pelted me, and concerned IT workers stopped to offer me lifts. At one point, after turning off a dangerous railway track by climbing a steep slope held together by pine trees, I became trapped in an empty quarry for several hours, before finally managing to scale a wire fence. All the while, I thought gratefully of Leigh Fermor — for without his example, I would never have thought it possible to have so much fun.

I have walked through medieval towns with my eyes glued to a Lonely Planet as often as the next person, but the magnificent journey recounted in A Time of Gifts made me wonder if today’s travellers tend to undervalue recklessness. Not everyone wants the same thing, of course, and it’s perfectly reasonable to put comfort and ease ahead of danger. But many travellers seem to crave something more than what they currently have. Most of us have at some point lamented that ‘all temples are the same’; that ‘this beach is overrun by tourists’; or that ‘I wanted the Taj Mahal and all I got was a thousand selfie sticks.’ For this group of disillusioned or dispirited adventurers, could there be another mode of travel out there, waiting to be rediscovered?

It’s often said that the rise of internet has made the world smaller place, and this is partly true. If Leigh Fermor had an iPhone, an Instagram account, and a habit of using Trip Advisor, the thrill of his adventure would almost certainly have been diminished. Had he used Google Maps, he would have missed the wrong turns that led him to so many serendipitous encounters. Had he striven to tick off a bucket list, he might have been able to shade more countries on his world map — but the essential aimlessness of his travels would have been lost. Technology facilitates travel; but this is perhaps an oxymoron. The word travel shares its origin with travail. Both come from the Old French travailler — to toil, to labour. Without struggle, without surprises, might we simply be cruising?

Fortunately, the idea of a ‘shrinking world’ is an illusion that can be swept aside at will. The surface of the Earth is as large, diverse, and colourful as ever. To avoid the prosaic and rediscover the poetic takes a shift in habit and mindset — away from ‘doing Vietnam’, and back towards a little recklessness à la Patrick Leigh Fermor. Romance and recklessness, the richest garnishes of adventure, can offset even the blandest consequences of globalisation.

This article originally appeared on Medium and is republished here with permission.

Featured image by Unsplash