DIGGING AT the bottom of a dusty drawer recently, I unearthed the most beaten and decayed of two dozen well-worn notebooks — a fragmented collection of half-baked words, thoughts, ideas, and narratives from over three years traversing under African skies.

The cover, “Loliondo,” scribbled in fading ink, instantly brought me back to a single moment, in 2011, well past midnight on the outskirts of Samunge village, deep in the bush of northern Tanzania. MaryLuck Kweka, a bright, beautiful, and healthy 11-year-old student from coastal Tanzania, stood illuminated in the dim headlights of a Land Cruiser. Her mother, standing nearby, explained to me that although she looked full of life, “she might be sick.”

“You never know what’s on the inside,” she added.

MaryLuck and her mother were on the long road to Loliondo, not in search of a cure for the known, but some sort of healing from the unknown.

Sixteen of us — a few mother-and-daughter pairs, businessmen, a government economist, a woman who held a prayer session each time the engine roared to life, and Max, my trusted translator — were packed into a Land Cruiser to see retired Evangelical Lutheran pastor and “miracle healer” Rev. Ambilikile Mwasapile, known to most as simply “Babu wa Loliondo.”

For months, Babu had captivated Tanzania’s attention, drawing a massive migration of people flocking by bus, car, motorcycle, Land Cruiser, and — for the fortunate few — by helicopter from across the country, and in fact the world, to his tiny rural village. At one point, over 20,000 people per day were arriving at Loliondo to see him and drink magical remedy.

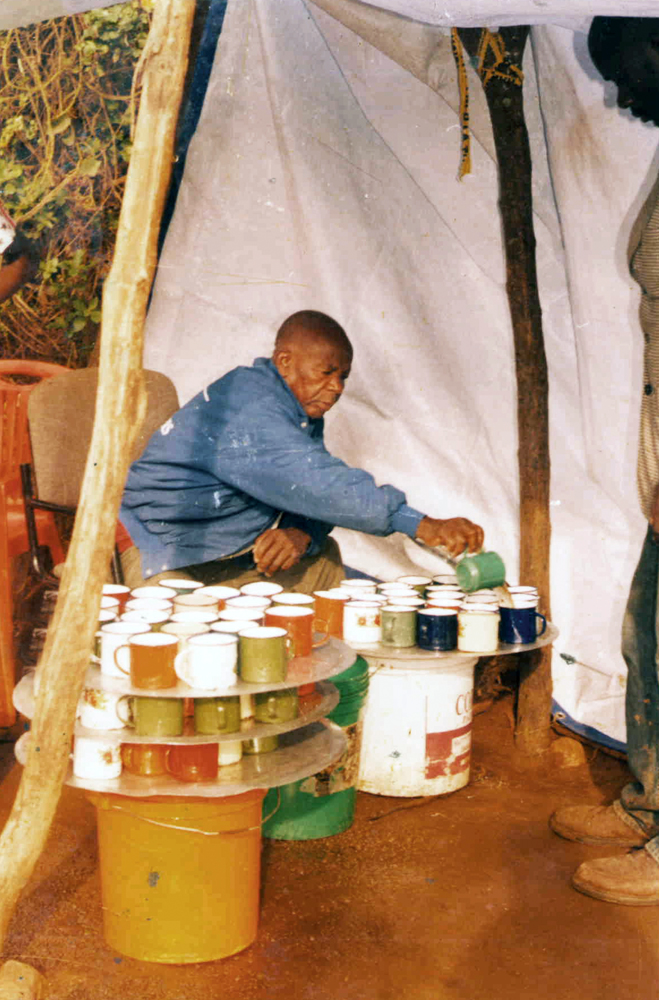

Babu’s “Cup of Miracles,” or “Kikombe kwa Dawa” (“cup of medicine”), was a “secret” potion, derived from the Carissa edulis plant (known locally by many names, including the mugariga tree) was said to cure those who imbibe it of everything from common headaches to diabetes, asthma, epilepsy, cancerm and HIV/AIDS.

Yet it was not the plant itself that contained the cure. It was the distilled drink, according to Babu, which contained the “power of Jesus,” brewed solely by Rev. Mwasapile himself, and consumed only within the gates of his compound, and by those who truly believed, which held the cure.

For me, the journey was about curiosity. For Max, it was because I was paying him. For our fearless and MacGyver-like driver, Raphael, it was his job. But for the other 13 passengers pressed together in the Land Cruiser, it was faith.

HIV is still a serious problem across Tanzania, and the country’s ability to curb it is still limited, funded primarily by foreign donors and governments. In fact, the state of the entire healthcare system is practically in shambles. Patients must buy their own needles, antiseptic wipes, and even bandages during hospital visits.

Yet the faith of Tanzanians remains strong. While 62% of the country is Christian, an overwhelming majority holds strong beliefs in traditional medicine, witch doctors, and the village “medicine man.” For them, a strong faith may be the best, or only, alternative to an ineffective healthcare system.

As my fellow passengers and I bounced along long-forgotten roads throughout the night, passing desert moonscapes, charred volcanic mountains, and salt lakes on the seven-hour journey from Arusha to Loliondo, over shared snacks I asked many of them why they were seeking Babu’s cure. Like MaryLuck, none of them appeared sick — at least on the outside. And none of them revealed to me they were.

Instead, they likened their journey to a pilgrimage. Did they truly believe in Babu’s claim (which in my mind was outlandish at best, and downright dangerous at worst, for if chronically ill patients stopped taking their medicines, thinking they were “cured,” they could, and in some instances did, die as a result)? Yes. Were they seeking a specific cure? No.

They were seeking a different kind of healing — a spiritual cure. People travel from around the world to visit the holy sites of Jerusalem, to circle the Kaaba at Mecca, take the road to Santiago.

For most Tanzanians, regardless of faith, these global pilgrimages, tests of faith, spiritual fillers, are inaccessible. So what’s wrong with a little homegrown hero, a local and affordable pious path?

At first, I thought, there’s a lot wrong with it. I took Babu as a hit-and-run swindler making a quick buck duping hundreds of thousands of innocent believers. Yet gradually, through the journey, something different emerged. I realized this wasn’t entirely the case. After we waited in line, heard Babu speak, drank our miracle-aid out of little multi-colored plastic cups, and turned for the long road back home, I witnessed a sense of relief and pride sweep over my fellow passengers. They had pledged their faith, nourished their souls — and if it happened to cure their diabetes, even better.

A few hours after downing my cup of miracles — an earthy, grubby, minty-tasting concoction — Jennifer, the young recent college graduate from Dar es Salaam sitting next to me, quietly asked, “Are you feeling any different?”

I responded honestly. “I’m exhausted, but no, I don’t feel any different than before.”

Smiling, she turned to me and shook her head slightly. “It’s because you don’t believe.”

I still don’t believe in Babu’s ability to cure the world’s most pressing diseases. But I have started to believe in his ability to give people something they need even more: hope.