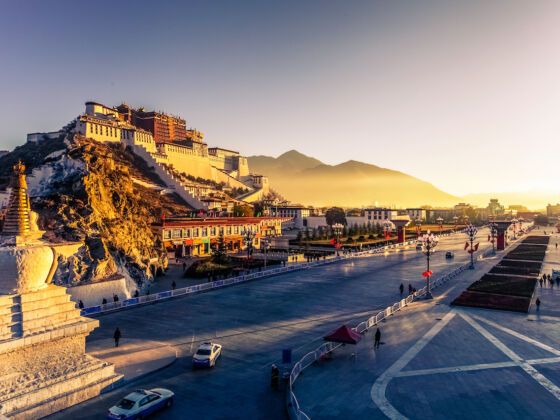

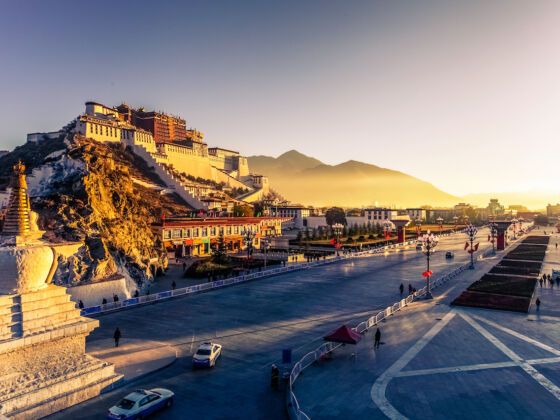

Talk to any Westerner with a deep (and maybe reductive or patronizing) love of Buddhism, the Dalai Lama, tantric rituals, or even just general “New Age” thinking, and you’ll probably find that a trip to Tibet is on their bucket list. Films like Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet have portrayed the Roof of the World as a stunning land of dignity and spirituality. Guidebooks trumpet the majesty of the Potala Palace in Lhasa or the grandeur of Mount Everest or Mount Kailash. These images can paint Tibet as the kind of of place where a tourist is bound to experience some deep revelation.

And thanks to development in China, it’s now easier than ever to get to the Tibetan Autonomous Region via oxygenated trains and decent highways.

Unfortunately, the reality of Tibet is quite different. Traveling to the TAR is a good way to be underwhelmed by the realities of rapid industrialization, “Disneyification,” and authoritarian control. Rather than visions of wild lunar landscapes, you’ll be confronted by aggressive mining and manufacturing. At major historical sites, you’re more likely to voyeuristically observe Tibetan culture than engage with any part of it genuinely. When you do encounter genuine spirituality in practice, chances are you’ll find people disrespecting it — pulling monks out of their prayers for a forced selfie, for instance.

Even worse, most revenue coming from tourism in Tibet doesn’t support local people. Instead, it’s usually Han Chinese migrants who’ve come to develop the region and who own its tourist shops. As a tourist in Tibet, you’re mostly subsidizing the Chinese government which is often driving tourism at the expense of the Tibetan people. And, because all travel in the area is mediated and regulated by the Chinese government, your movements as a tourist will be circumscribed—and you’ll still be moving more freely than many who actually live in the TAR.

Some people feel that the best way to escape this Chinese-mediated view of Tibet-proper is to visit the exile communities in India or Nepal. But many of these towns — like the New Delhi quarter of Majnu Ka Tilla — aren’t set up for tourists. And those that are—like Dharamsala’s McLeod Ganj (where the Dalai Lama lives and where the Tibetan state-in-exile keeps its headquarters)—- can be so geared towards tourists that it hurts. The town, in my own experience and those of others I’ve spoken to, is an endless stream of backpackers getting Buddhist tattoos and buying prayer beads from Tibetans who serve them to make a buck, amidst a backdrop of a carefully crafted and unified Tibetan identity of peace and faith. This may satisfy some travelers looking for egregious spirituality. But there’s still artifice about it.

Fortunately for those who want to get a glimpse of a Tibet relatively unfettered, wild, and open for immersion, there’s a little-appreciated alternative route: visiting the parts of Tibet-proper that aren’t part of the TAR-proper. The tightly controlled TAR only corresponds to the region of Ü-Tsang in Tibet, the territory controlled by the Dalai Lama before the Chinese inserted themselves into the picture in the 1950s. But beyond Ü-Tsang, Tibet as a cultural and geographic region also includes the regions of Amdo and Kham, which existed semi-independently in the mid-20th century and which were separately absorbed into China (with Amdo becoming the province of Qinghai and Kham getting split into subsections of Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan, respectively).

Because these regions had a different trajectory than the TAR, they never faced the same crackdowns (or at least crackdowns to the same degree) and were given far more leeway. For example, some people in these regions can still talk freely about the Dalai Lama. They’re also underdeveloped by Chinese standards and rarely visited by non-Chinese outsiders. As such, in my own experience and those of other travelers in the region I’ve spoken to, it’s much easier to find Tibetan-owned businesses to patronize. It’s easier to find monks and nomads practicing their trades freely without concern for onlookers. And, it’s easier to explore its stunning frontier by hitchhiking or wandering aimlessly rather than via prescribed routes and means. Of course, there are elements of Chinese control in these regions too, but not with nearly the same warping effect as in Lhasa.

That said, visiting Amdo and Kham is hardly a replacement for visiting Ü-Tsang. Despite the impression you may get in McLeod Ganj, Tibetan culture is quite diverse, and the people of Kham tend to come from different spiritual and social backgrounds and mindset than those in, say, Lhasa. And although you’ll be patronizing Tibetan businesses, ultimately your presence and tourism dollars still wind up endorsing and bolstering a regime which many Tibetans feel oppresses them at worst, and profoundly dissatisfies them at best.

But if you’re dead set on visiting Tibet, this route is the best way to achieve a degree of contact, reality, and freedom of movement and engagement that you just can’t get in the TAR as an outsider today. By visiting Amdo or Kham, tourists can also move beyond the cinematic view of a peace-baby Shangri-La and towards a more complex, nuanced, and altogether (one would hope) satisfying understanding of Tibet as a huge, diverse, real land.