It’s always been a bastard genre, of dubious utility, of uncertain reliability, generally unpleasant to sift through, practiced in a great percentage of cases by amateurs and hacks — or worse: boosters and opportunists —, and inherently quick to obsolescence. Now, finally, in the age of GPS, Wi-Fi, googlemaps and lithium-ion batteries, maybe it’s time we let it go.

Here’s the thing: my publisher wants to put together a second edition of my book. The thing has earned a certain amount of acclaim, for what it is, but has not yet made it into the hands of all four million people who each year travel through the region in question, gleaning information (or not) from who knows what combination of other sources. And so the question arises: how different should the second edition be from the first?

“…you may reach my country and find or not find, according as it lieth in you, much that is set down here. And more. The earth is no wanton to give up all her best to every comer, but keeps a sweet, separate intimacy for each.”

Is it just a matter of updating phone numbers, noting changes in ownership and menu and the like, changing marketing strategies, getting the word out more effectively, or… what?

What do travelers want these days? Is Google enough? Or some combo of Google, Wikitravel, perhaps an authoritative iPhone guide app, available for download at the eminently reasonable price of $1.99, a couple of printouts from MatadorTrips, and/or whatever interpretive signage might be happened upon along the way? Plus — what the hell — a good spy thriller or a collection of Dr. Seuss stories to listen to in the car. Why bother buying a guidebook?

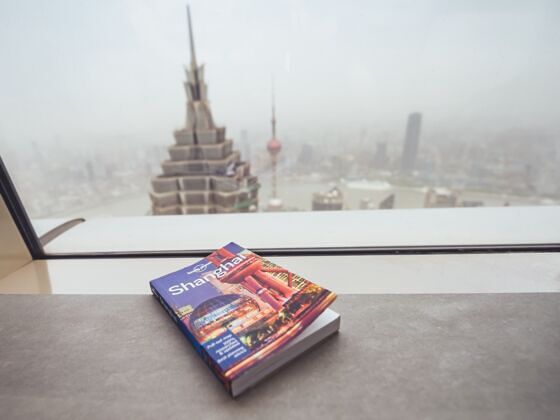

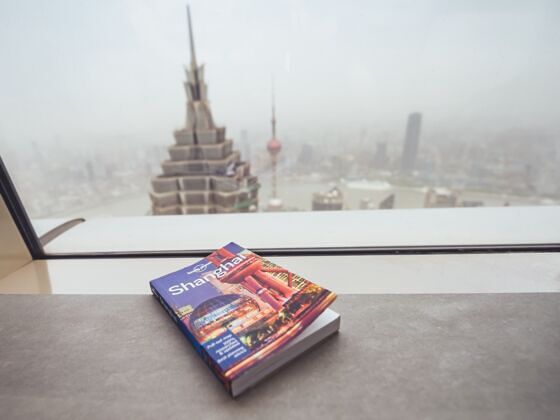

If it’s just for setting hot drinks on, coasters are cheaper (and often more attractive).

Traditional book publishers, it seems, still think there’s a market for books. We just have to figure out how to make the book do what it does best, they say — and leave the rest to the newer media. “We want to structure [new books] to more accurately reflect just how they can be most effectively used in the age of the internet and GPS devices,” my publisher wrote in a recent email.

So what does a book do best?

Even back when a handy bit of last year’s beta might’ve spared you some rather momentous inconvenience— i.e. you better get out of Independence, MO, by the first of May (oh, and avoid the so-called Hastings Cutoff), or by December you’re likely to be snowed in and chewing on the twice-boiled bones of your traveling companions — even back when a hand-sketched map on the back of a linen cocktail napkin was all you had to go by, it was never much of a substitute for wide-open eyes, an ingrained feeling for north, a sturdy constitution (or a big gun), and a modicum of common sense.

Personally, I’ve found myself in a number of situations in which the AAA guide to Baja or a particular water-stained bouldering guide to Joshua Tree has proven eminently more useful in the starting of a fire than as originally intended.

Not that it wouldn’t have been useful, back in the day, to know how to make words for “is the water safe to drink” in Paiute, or “I’m so sorry I stole your melons you can have my half-starved mules in exchange no worries” in Comanche. Not that it wouldn’t have been helpful to have an opinion as to how much bacon to lay in for the journey, how much flour and how much gunpowder. Or these days, just how necessary is it, really, to winterize that rental RV?

But it’s always been the traveler’s responsibility to take the guidebook, however seasoned, as just one among many sources of information (and perhaps not the best, or most up-to-the-minute).

As a traveler who prefers to ferret things out on his own, to skip the well-paved interpretive loop and instead wander off-trail in search of the overlooked and overgrown, I can’t say I’ll much lament the passing of the genre (assuming, that is, that the rumors of its demise have not been greatly exaggerated). Give me a half-decent map, a good 19th-century explorer’s narrative, a gallon of water and maybe a headlamp for good measure, and I’ll set off across the landscape giddy into the unknown. When I get that hankering for a decent Philly cheese steak or a sixer of empanadas de pino, I’ll risk altercation and embarrassment and ask a local — long before I try to hack my way to something useful through the thickets of TripAdvisor or Yelp.

As the author of an old-fashioned printed-and-bound guidebook, though, I worry. I wonder if it may finally be time to decamp. Or (gulp) to reinvent.

Across the board, the instincts of trad publishers (and really, who am I to argue?) are to go glossier, sexier, with catchy mag-style layouts and full-color photos. They want less text, fewer individual listings (where the reader might have to sort through and make a decision from a well-honed lineup), and more authoritative top-ten round-ups, more what-to-do in 24 or 36 hours — in other words, the sort of ephemera that I, personally, flip through more for the breeze it creates on my face than for the information I might take away (and then I throw it in the recycling bin).

The problem with glossy photos in a guidebook — aside from the needless redundancy, the straight representation of landscape or swimming hole or hotel facade, the real version of which I hope to see in person, for myself — is that color-printed paper is not as good for starting fires as black and white.

To quote fellow traveler and veteran freelancer Robert Earle Howells from a recent online interview: “I was always less interested in places per se than in backstories, history, legends, and people.”

For my money, this is what good travel writing works for — in whatever format, but especially that which aspires to travel with you in your handbag or your glove compartment, thus to “guide” you through new and otherwise foreign landscapes.

For me a good travel guidebook works to fill in the context of a place, to help me understand what’s at work below the surface, rather than merely to instruct me where to eat or sleep, or to provide dots for me to connect along the way.

But what do I know? I hardly ever use guidebooks. How about you?