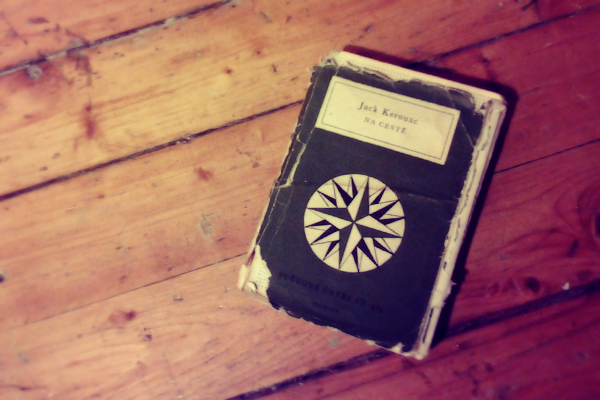

I was given a copy of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road by my father the summer before my fifteenth birthday. The book had seen better years. Its pages and spine gave the impression of frailty shored up by masking tape. My edition had been published in 1978, but not by Penguin or Random House — instead, the back cover lists the Czech publisher Odeon, along with a list of the eight titles in their World Literature series for that year.

What 'On The Road' Meant to a Girl Growing Up in Eastern Europe

On the Road is the only English novel on the list, and I remember thinking how remarkable it was that this version of the book existed at all. 1978 was, after all, in the dead middle of Communist Czechoslovakia’s Normalization period, a sort of state-enforced regression into a sexlessly grey socialist status-quo. The Normalization was the reaction to the events of the heady and tumultuous spring of 1968, and the order of the day was to keep one’s head down, carry on, avoid asking too many questions, and by and large ignore the existence of a non-Communist world entirely. I could not fathom translating and publishing a book like On the Road in that atmosphere.

The book needs little introduction. Jack Kerouac’s thinly fictionalized account of his manic drives across the States with fellow Beat poet Neal Cassady has over the past fifty years become a classic. Popular topics: driving, drugs, sex, jazz, parties, girls, gas stations, life force. Kerouac famously fed a scroll of teletype paper into his typewriter and wrote the novel in a feverish three-week push.

Its impact on publication in 1957 was huge, and Kerouac became a reluctant overnight star. Here was the manifesto of the Beat generation, a sensational break-the-rules tract from a culture that stood in defiant opposition to the repressed domestic idyll of the American fifties.

Of course, the book had (and has) plenty of opponents. Initial reviews were mixed, with some critics declaring it morally objectionable while others (notably, Times critic Gilbert Millstein) calling the work groundbreaking and artistically relevant. Kerouac’s often masterful stream of consciousness prose and unabashed zeal for life resonates strongly with some readers. Others — and sometimes I fall in their camp — find Kerouac’s roaring escapism frustrating and perhaps at times shallow. Despite such criticism, On the Road remains the archetypical American road novel.

That summer, I went against imperatives to always read the work in the original and spent my free moments with the fragile pages of Na cestě. I was living and working at the time in a monastery in rural Bohemia and my surroundings could not have been more idyllic, nor could they have been a sharper contrast to Kerouac’s America. The backdrop of my introduction to the Beat generation of Americana was not a bus stop in the Midwest but an eleventh-century church and the general store at the corner of the village square.

Coming to North America from the Czech Republic forever shifted my idea of distance. I’ve driven across the prairies whose famous defining feature is their featurelessness, the vastness of plains of grass and planes of red earth that make seeing a roadsign feel like a momentous occasion. I’ve been drunk and telling stories to keep the (sober) driver awake, as nighttime company across the highways of wooded Canada. I remember the times my dad and I would listen to Deep Purple at three in the morning driving from Philadelphia towards the rivers of West Virginia some three hundred miles away.

I once biked over a hundred miles from Montréal to southern New Hampshire in the middle of the night, ostensibly for love but likely more for the liberty which exists in linear movement through space, in the democracy of sheer distance. It was a substantial journey then, especially since halfway through it started snowing, but on a map of North America it barely shows up; there is so much more ground to cover.

If I traversed the same distance (demarcated by smaller, staider, more sensible kilometers) in Czech Republic, I would have gotten practically to the other side of the country. I’ve done that, too, but the sense of careening limitlessness was absent. There are no wild swerving highways in the Czech Republic — the vast majority of roads are narrow and winding and poorly maintained and shaded by trees carefully planted many years ago that bear fruit in the summer. Going 20 kilometers to the next town over counts as a trip.

This difference of scale is the crux of what is so fascinating to me about the Czech translation of On the Road. In Bohemia you cannot, as Kerouac and Cassady did, drive the distance from Flagstaff to St Louis — you’d have hit Belgium before you were halfway, and besides, in 1978, there was a pretty substantial wall in the way. In short, there is almost no room to wander in our country. Bohemia is often compared to a garden — our mild and fertile river valleys have been tended to, lived on, and farmed for millennia. There are no extremes, and there is no distance.

Yet, somehow, On the Road resonates. Whether despite the lack of distance or because of it, the romanticism of movement through vast spaces has a place in Czech culture. Some of my earliest memories are of singing songs about a romanticized idea of Going West. There are Czech songs about El Paso and Johnny Cash and El Dorado and covered wagons, even though for the authors or translators of those songs, America was little more than a hazy ideal in the distance. My favourite song when I was six was a narrative about hunting whales in the Arctic Ocean, never mind that Czech Republic is thoroughly landlocked.

My dad told me that when he read On the Road, he fully expected to live and die in the Communist east. In 1978, it seemed that Flagstaff and Tulare and Cincinnati would remain for him names on a map. But my countrymen would sing songs about them nonetheless, and climb the Slovakian mountains if they couldn’t get to the Sierra Nevada, and leave the cities to wander through the woods of the countryside where the banality of the everyday and the oppression of the ruling party couldn’t get at them. Thirty-four years later, the old frail book on my bookshelf is a testament to that resonance.