Finding the start of Colorado’s Pot Trail

“I’ve never smoked a joint in my life,” said the grandmother next to me. She was holding a huge, lit, pre-rolled bomber cone. You could tell she was deliberating.

Her name was Bernadine Swale. She was originally from Botswana but had lived in Denver for three decades and raised her family here. She was the oldest of the dozen guests that included a young couple from Miami, another from Dallas, and a middle-aged foursome — all of us onboard a party bus rolling towards a “grow” (cannabis cultivation facility) north of Denver.

She passed the joint on and smiled at me. “I’m just fascinated with the whole thing,” she said. “I mean it’s made such a big difference to the city and I wanted to find out about it.”

Coming back to Colorado for the first time since legalization (I lived here in the early 2000s), I hadn’t figured on meeting someone like Bernadine on a weed tour. But then it made perfect sense. These tours are a kind of entry point for thousands of people from the US and around the world coming to smoke legally. The guides at My 420 Tours, one of Denver’s first pot tourism operators, serve almost like weed ambassadors and educators. They teach how cannabis is grown, regulated, and sold, and facilitate people — in our guide Gauge’s words — “getting nice and elevated.”

“How has it made a difference?” I asked Bernadine.

“It’s just brought a lot of new people into the city. We were pretty liberal and open beforehand, but I think it’s made it even more so. I’m actually a retired pharmacist, and I was really against it. I thought ‘Next thing I’m going to have to be giving out marijuana in the middle of my shift along with the Oxycontin and all this other nonsense I’m giving out.’ But as a pharmacist I’ve actually seen a reduction in prescription drug abuse. I mean it’s still pretty bad, but I’ve seen a lot less of it than I did prior to them legalizing.”

“And I thought it was going to be real bad for the city. I thought we were going to have a load of crime, that we’d have people stoned all over the place, that nobody was going to get up to go to work. And it’s all been the complete opposite. It’s the best thing that ever happened to the city.”

With the passing of Amendment 64 in 2012, Colorado became the first state in the US to legalize recreational marijuana. The first retail sales began January 2014. This lead time created huge momentum — the “Green Rush” — for establishing cannabis-related businesses: dispensaries, grows, private events, clubs, and tours.

The level of success blew away everyone’s expectations. The first year, 2014, brought in $700 million in marijuana sales. By 2015, annual sales were just under a billion dollars. The first detailed studies of the economic impact of cannabis in Colorado showed over $2.4 billion in total economic activity, with over 18,000 new jobs created in 2015.

That year, over 100,000 people moved to Denver, and the city was second only to San Francisco as far as the percentage increase in housing costs. This trend has continued, with record high housing costs and record low inventory through winter 2017-2018.

And so while many people I spoke to echoed Bernadine’s “best thing that ever happened to the city” sentiments, the flipside was incredibly rapid gentrification. Many longtime residents could no longer afford to live here. On the way in from the airport, for example, my Uber driver, Terri, a Coloradan in her early 50’s, talked about the struggle to afford living here as an everyday working class person.

After an ID check, we entered Euflora’s grow. Inside the first of two huge rooms (together they totaled 7,000 sq. ft.), dozens of knee-high marijuana clones grew under natural light.

Nearly all cannabis cultivation today happens in old warehouses retrofit with grow lights. It’s a very energy-consumptive business, with a nearly $6 billion dollar electric bill for all cannabis grown in the US in 2016. New LED lighting technologies are helping increase efficiency, but Euflora has the ultimate setup as an actual greenhouse, the first such facility licensed in Colorado.

From here we moved around the building, passing two enormous exhaust fans ventilating an almost overpoweringly pungent marijuana wind. Everyone took turns standing right in front of the fan and breathing it in.

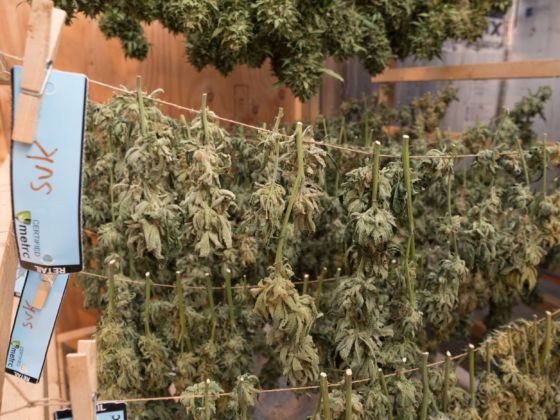

Then we entered the flower room. Here hundreds of chest- to head-high plants drooped with heavy trichome or crystal-covered buds. Elise started talking about soil composition and technology, how the whole operation could be run off a smartphone, but everyone seemed to be sort of stunned, gaping at the buds. Even on just the level of a greenhouse growing flowers, it was impressive, an indoor marijuana forest.

Euflora Dispensary – 16th Street Mall, Denver

My preconception of a marijuana dispensary was something between a pharmacy and the bulk food sections of a health food store. I imagined a fatherly, white-coated attendant standing behind a counter.

But Euflora, arguably Denver’s most premier location dispensary (right on the 16th Street Mall) wasn’t anything like that. It was basically like the Apple store, only for weed. Dozens of strains sat in vented containers alongside digital tablets with comprehensive descriptions about THC percentage, Indica vs. Sativa. And inset into the walls were brightly-lit displays for every kind of edible (mints, gummies, gourmet chocolates), oil, tincture, and vaporizer imaginable.

Beyond the setup, what struck me most was the crowd. Over the next 45 minutes, dozens of different people came in and out. And while plenty of people were in their 20’s, there were actually more middle-aged customers, and they, far more than anyone, were like kids in a candy store.

One group arrived with suitcases in hand, obviously straight from the airport. Another group of various ethnicities — all wearing conference badges from a local supercomputing conference — bought enough marijuana gummies to get 100 people stoned. And we looked on approvingly as Bernadine purchased a bottle of cannabis soda.

Unlike everyone else though, I couldn’t find what I was looking for. I had naively hoped to be able to buy CBD flowers. Among marijuana’s 113 known cannabinoids (chemical compounds that trigger cannabinoid receptors in our brains) cannabidiol, or CBD, is not a “euphoriant” like good old THC, but has other medicinal properties I wanted to experience — particularly its scientifically proven “downregulating impact on disordered thinking and anxiety”.

As I was soon to learn, however, CBD flowers were used to make oils, tinctures, and (for people who really wanted to get wild), dermal patches. Getting actual CBD flowers was possible, but only at medical marijuana dispensaries, and that would take a medical marijuana card. (At Euflora’s other location on Brighton I’d later find their “Pure CBD” which was still 5% THC.)

As our group collected back up, photographer Brian Lewis and I laughed at the map that Euflora customers had filled with pins designating where they were from. The US was completely blanketed. There literally wasn’t room for a single, additional pin anywhere. All European major cities, all South American major cities: blanketed. The Australian coasts: blanketed. Japan: blanketed.

At that point, the security guard, a skinny, millennial veteran with a Glock on his hip and a slightly amused expression, as if he couldn’t quite believe his luck in guarding this place, pointed to the map.

“That’s my favorite one there, see it?”

“No,” I said, “Which one?”

“North Korea.”

From skid row to RINO

Brian dropped me off in Five Points near Curtis Park. I was stoked to stay here, in Denver’s historically African American neighborhood (with a longtime Jewish population as well). This had been the “Harlem of the West” where Billie Holiday, Miles, and Dizzy played during the jazz heyday, and Jack Kerouac worked on On the Road.

I had the gate code for my Airbnb on Champa street and let myself in. Walking through the living room, it reminded me of a classic Athens, Georgia college house. They didn’t have a living room so much as a proper music lounge. There was the bong beside the sofa. The turntables set up. An Akai MPC for sampling/making beats. The host, DJ Musa, was a well known Denver hip-hop producer.

Upstairs I found a young woman changing the sheets. She looked tired, and I apologized for arriving a bit early, then invited her to a smoke. We went out to the front stoop.

“So you can just light up here?” I asked, packing a small bowl and passing it to her.

“It’s private property,” she said, lighting up, then passing it back. “Absolutely.”

To actually be sitting there smoking — legally — felt a bit surreal. I studied the yard, which was lit up warmly in the afternoon sun, and thought about private and public space. Ten feet away was a picket fence, and on the other side, the sidewalk. That’s where our private space ended and public space began. A dad passed by with his son on the way home from school, not giving us a second glance. Cars moved up and down Champa Street.

So far I hadn’t seen anyone smoking in public. On the tour, Elise made a point of warning our group: “It just looks bad to be smoking out in the streets. We like to keep it discreet here.”

Gauge added, “Wait until you’re back at the hotel. (My 420 Tours and other operators organize Cannabis friendly accommodations). And the parks are really nice; just slip into the trees.”

In this sense, smoking today in Colorado is effectively the same as smoking before it was legal. People do it privately.

But the idea isn’t just that cannabis should be legal, but that — like in Amsterdam — it can also take place in a variety of public settings such as bookstores, cafes, and other creative spaces that lend themselves to social interaction.

And so public consumption is really the final frontier for cannabis in the US. Amendment 64 legalized adult use of marijuana as long as it wasn’t “open and public.” This created somewhat of a legal conundrum because what constitutes “open and public” was never fully defined. The idea was to create a regulation model similar to alcohol, however, unlike bars where alcohol can be served legally, there was no provision for public cannabis lounges.

In late 2017, Denver County became one of the first counties in the US to attempt to define public consumption of cannabis. As Danny Schaefer, owner of My 420 Tours, explained, “They created a new consumption lounge license where operators like us can apply.” This has set off a race for business owners to get through the long application process and open the doors to Colorado’s first public cannabis lounge. As of yet (Jan 2018), no applications have been approved.

After a few minutes, Musa came out (apparently from a nap) and joined us. I asked him about how things had changed since pot was legalized.

“It feels like it’s been like this forever,” he said, laughing.

“Yeah man, but all around the rest of the country it feels like it’ll be forever until anything like this,” I said.

“The thing is, everything in this country is driven by money,” Musa said. “As soon as other states really watch how our tax revenues go up and how good this is for business, they’ll change.”

3000-2500 Larimer St., Denver

That afternoon I cruised back up to Mestizo Curtis Park and then west on 30th. Along Arapahoe and every other side street were remodeled Victorian houses and modern Dwell-style homes with shed roofs, all of it screaming rapid appreciation and gentrification. Earlier, when Brian and I drove through the edge of the RINO district and the industrial parks, data centers, and warehouses along Brighton Boulevard, you could see the same thing. The whole area was undergoing large-scale redevelopment.

Interestingly, the Airbnb hosted by Musa was a rare exception in that the investors took gentrification into account. Rather than buy the property outright, they had arranged a long-term lease and some kind of profit sharing agreement. This enabled the owners to retain the property while at the same time creating revenue — and more Airbnb offerings here in this traditionally African American neighborhood.

Musa had said something, though, that was amazing when you looked around now: “I grew up here. This is my neighborhood. And just 15 years ago there were still Crips and Bloods and gang violence all over the place.” Later, turning onto Larimer St., I found an old-timer who confirmed, “This used to be skid row.”

It’s worth just Google-Street viewing this section of Larimer Street — what used to be skid row — to see the flourishing businesses, the breweries, restaurants, gourmet markets, and street art.

When I asked the old-timer what changed everything, he answered simply, “marijuana.”

In Denver, for about $25, you can buy an eighth of an ounce (a full medicine bottle) of the highest quality marijuana.

Over the next 24 hours, I’d go back through my old hometowns, first Boulder, then up to Nederland and along the Peak to Peak where some of my oldest friends have hunkered down, living off-grid in the face of Niwot Ridge for the last two decades.

I visited another friend, whose latest venture — producing hemp oil (rich in CBD) — was just getting off the ground. They believed they’ve found a solution for themselves and many fellow local farmers who’ve struggled to make a living without resorting to conventional/unsustainable farming practices.

I smoked with a couple in their 70s — the man a closet Republican with stacks of Yale Alumni magazines — who talked about how their area has recovered after the brutal Lefthand Canyon fire and flood.

I caught up with my friends’ son, now a junior at CU on the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and interning at a cannabis events PR firm. He introduced me to his buddy, a fellow CU junior, who was majoring in biochemistry with a focus on cannabinoid research.

I viewed a first-of-its-kind exhibit on botanical illustrations of cannabis at the CU Natural History Museum.

I had dinner with fellow journalist and writer Bart Schaneman, who now covered cannabis business for the Marijuana Business Daily. He talked about their research, and how between California’s legal cannabis market (which opened Jan 1) and the projected growth of all markets across the US, we were looking at “a 50 billion dollar industry by 2020.”

And finally, I interviewed Kayvan Khalatbari, who was running for Mayor of Denver in 2019. An Iranian American, he’d come to Denver from Nebraska, and in a single decade created one of the most important cannabis companies in Denver before licensing it to Willie Nelson.

Indeed, the evolution of weed-tourism in Colorado — the burgeoning “pot trail” — is noteworthy (if a bit silly). The fact that you and your friends can fly into DIA, get chauffeured around Denver while smoking up, stay in “420-friendly” AirBnbs, hotels, enjoy sushi and joint-rolling classes or cannabis-powered yoga sessions or writing workshops: it’s a dream come true for so many.

But ultimately I found this other side of the trail more interesting — the way cannabis was evolving local economies, culture, medical research, and neighborhoods. The way it had changed people’s lives.

And so after nearly a decade, coming back to Colorado felt a bit like a victory lap. Not my victory per se; it was more like partaking in a group victory. A win, finally, for that friendly, far-reaching caucus: the kind-hearted stoners of America.

All that said, however, a moment early on in the trip keeps coming back to me. Before going on the weed tour, I wanted to just scout out the area first. It’s an old travel habit. A need for me to get the lay of the land slowly, with my feet first.

So I had the Uber driver drop me off in the barrio Latino. She said I was the first tourist she’d ever dropped off there.

I’d chosen the place for its name: La Potranca Taqueria. It was in a row of squat, plain buildings that housed the local Latino AA chapter, Grupo Alcoholicos Anonimos. Across the street was a putrid smelling Purina dog food factory. Directly overhead, traffic roared along I-70’s elevated roadway.

It was a gigantic industrial shithole.

But I was stoked. For some reason, these kinds of places — places with literally no “tourist value” — have always been the most interesting to me as a traveler. Terri had mentioned the name, Globeville, and that it was “one of the most depressed areas in Denver.”

She was putting it lightly: Globeville is technically the most polluted neighborhood in the United States, an area built on top of superfund and brownfield sites — legacies of smelting and industrial activity that go back to the 1800s. Now it was the barrio Latino and ground zero for Denver’s “grows” (cannabis growing operations).

I peeked in at La Potranca. A taped up piece of paper said Hay pozole. But then suddenly I wasn’t feeling hungry and decided to keep moving.

As I started down Josephine Street, the freeway noise died out, and I found myself completely alone. On the east side of the road were sections of ugly brick duplexes mixed in with old Victorian cottages — classic Denver style houses with front porches and cottonwood trees. On the west side stood various commercial buildings and industrial areas. The pungent smell of marijuana drifted in and out from all directions.

Even if Globeville was off the radar for most people coming to Colorado, this is where the plants grew. This was where the high came from. This is what had for so long been illegal. The morning sun faded now behind high cirrus clouds, but there was still a warm wind. And in a strange, solitary, and sober moment, I felt as if somehow I’d found the start of the pot trail.

Videos and Writing by David Miller

Photography by Brian Lewis