If you want to understand the state of the planet, look to the Great Barrier Reef. It’s long been considered one of the world’s most impressive natural wonders. But as more scientists study the GBR, many now also view it as an early warning system for climate stress. Recent news documented by the BBC, Reuters, and scientific organizations like the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) tell an alarming story. In many parts of the reef, up to one-third of the hard coral disappeared in just one year, following a brutal mass bleaching event during the 2024-25 summer.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Is in Crisis. Here’s How to See It Now.

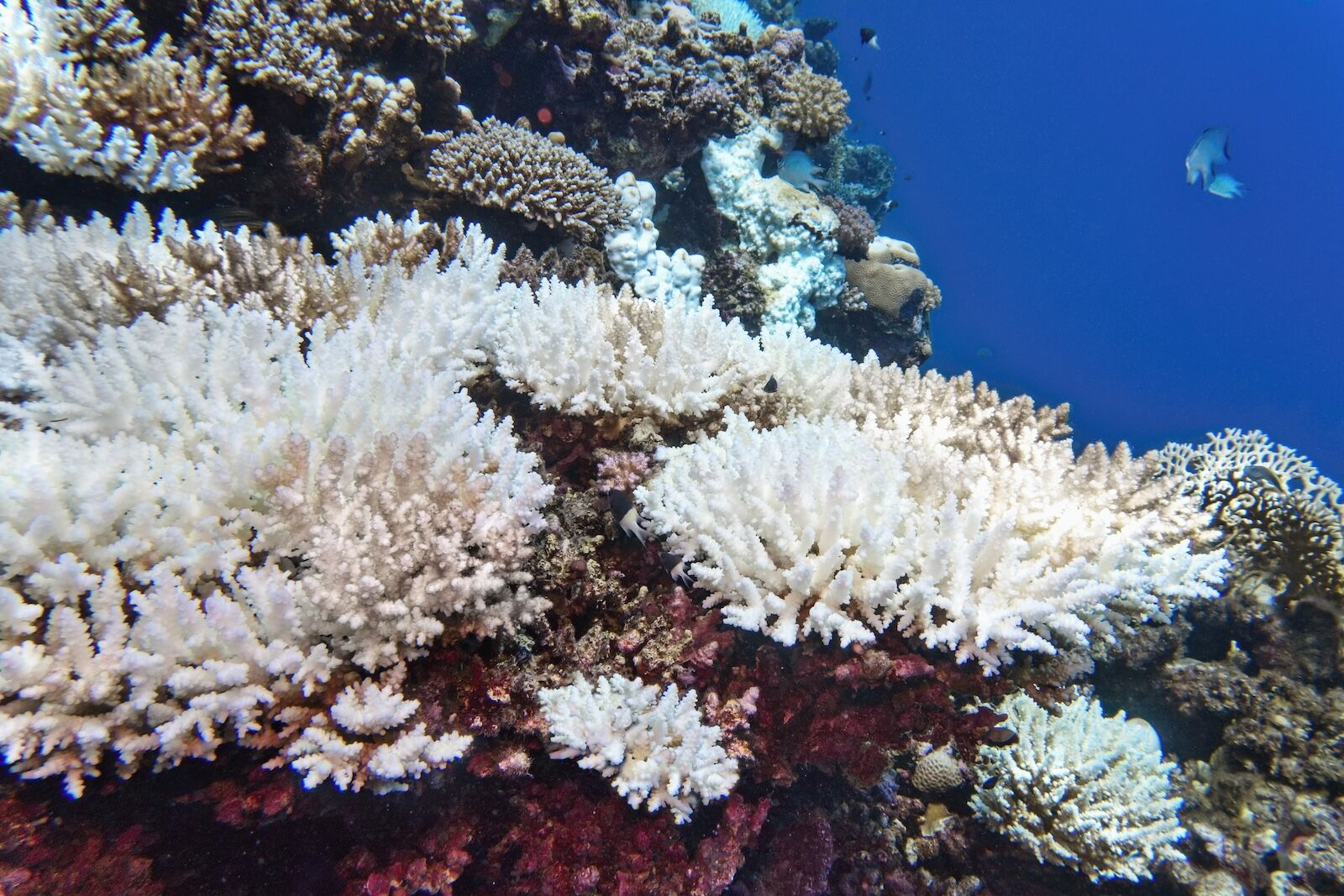

The 2025 AIMS report shows the worst recorded annual decline since the organization started studying the reef in the 1980s. The organization’s in-depth monitoring make the causes of the decline clear: severe marine heatwaves raised ocean temperatures beyond what most corals can handle, leading to vast coral bleaching. And bleaching doesn’t just mean more pale corals — it’s indicative of stressed and starving coral, and is often the precursor to massive coral deaths. Adding to the problem is the thriving population of crown-of-thorns starfish, a native but aggressive eater of coral that’s munching its way through already fragile reef areas.

For travelers who want to see the reef, it’s best to plan a trip soon — and to take action to address climate change to hopefully improve the reef’s future health.

Bleaching of Acropora coral on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo: Tunatura</Shutterstock

While coral populations ebb and flow, it’s clear that the reef’s health is trending downward, despite some notable reports on resilience in some parts of the reef. Though even news of increases in coral cover can be misleading. If that cover is made up of weak coral or one type of coral is outgrowing all others, that can indicate a loss of biodiversity.

Mass bleaching events used to be rare, but since 2016, there have been five major ones on the Great Barrier Reef: 2016, 2017, 2020, 2022, and 2024. According to NASA and AIMS, the 2024 bleaching event is the largest to date, with the north, central, and south sections of the reef all impacted. Scientists say up to 60 percent of individual reefs experienced severe heat stress. The finding lines up with global reports on rising temperatures, which suggest that the world is quickly getting hotter year after year, and will likely continue to get warmer at a faster and faster pace.

Is the Great Barrier Reef’s declining health a new problem?

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Australian Institute of Marine Science (@australianmarinescience)

On a global timescale, the declining health of the GBR is brand new, and coincides with an uptick in human development and industry. But on a human scale, the problems have been known since at least the 1980s. About half of all coral cover was lost between 1985 and 2012. And while there have been moments when corals seemed to rebound, those windows of recovery are getting fewer and further between. The reef is now unstable, with record high coral cover one year that’s wiped out by record losses the next, though the population is generally trending down. Matador Network has been reporting on the trend for the last decade.

Interventions — like culling crown-of-thorns starfish — help on a local scale, but can’t reverse the damage from heatwaves that stretch for hundreds of kilometers. Scientists working on the ground say they can see the pattern changing in real time.

Dr. Mike Emslie, who helps lead annual monitoring at AIMS, has written about a system battered so frequently, and with such force, that recovery might not keep up with damage for much longer. The reef has a dramatic ability to recover, but it requires a break in stressors, which coral are unlikely to get if current global trends continue. “We’re heading towards a future where hotter water temperatures will likely cause bleaching every year, along with ongoing threats of cyclones and coral-eating starfish,” he wrote on the AIMS website. “Recovery requires reprieve – and those opportunities will diminish as climate change progresses.”

Is it too late to see the best of the Great Barrier Reef?

Photo: Coral Brunner/Shutterstock

The Great Barrier Reef has shown an ability to recover quickly, so theoretically, it could be the healthiest it’s ever been in another five or 10 years. But that would require global actions to reverse climate change and the associated impacts, like more extreme weather. So far, that hasn’t happened, with global temperatures steadily climbing upward in the last 150 years. The urgency to address climate change is hard to overstate. Scientists from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority emphasize that the outlook for the reef is “one of future deterioration due largely to climate change. This is despite some habitats and species improving over the past five years.” As of 2025, the reef is certainly not at peak health.

Travelers who want to see the reef at its maximum health should act quickly. Experts from around the world have estimated that if current trends persist, 90 percent of living coral could disappear from the central and southern reefs in the next 10 years.

In the past, the northern part of the reef has been the healthiest, thanks mostly to its more remote location that’s farther from polluted runoff and the storms that tend to stay farther south. The northern area also historically has fewer crown-of-thorns starfish, which breed faster in warmer water and can find more food when the coral the starfish prey on is weaker. But one recent report found that coral decline was the smallest in the central part of the reef.

How to maximize a visit to the Great Barrier Reef today

A woman on board a boat on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo: Suzie Dundas

Travelers hoping to see the healthiest possible areas of the Great Barrier Reef should take a proactive approach when it comes to planning — and participate in conservation-oriented activities while they’re there. Here’s how to maximize your chances of seeing the GBR’s healthiest, most thriving regions.

Choose operators with expert knowledge of the reef

Tour operators and guides, especially those based in hubs like Cairns, Port Douglas, and the Whitsundays, have up-to-date local intelligence on which reef sites are faring best. Many also lead or participate in reef health and biodiversity-monitoring programs, like Eye on the Reef (which also allows visitors to participate). These guides are the most likely to know where to go for the healthiest, liveliest reefs — especially for diving and snorkeling. Do your research to ensure you’re booking activities with thoughtful, conservation-minded operators, like Diver’s Den (for snorkeling and diving), Mandingalbay Authentic Indigenous Tours (for wildlife and boat tours), or Spirit of Cairns (for dinner cruises and charters). Supporting the right guide companies can ensure your tourism dollars support reef conservation efforts.

Visit the central Great Barrier Reef sites

The recent AIMS study showed that the most stable and resilient section of the reef, as of now, is the central region. About 10 percent of surveyed reefs saw an increase this year, and many reefs farther offshore still have significant amounts of healthy hard coral. Look for tours that can go to the outer reefs in a day, or consider booking an overnight stay closer to the outer reef. Lizard Island offers luxury bungalows on an island on the outer reef, while liveaboards like the Spirit of Freedom and OceanQuest offer the chance to sleep on a boat for a few days directly above reef dive sites. Multi-day trips allow boats to access farther away, less-visited reefs, increasing the chances that they’ll be less impacted by causes like runoff or crown-of-thorns starfish (nutrient runoff creates plankton blooms, which feed starfish larvae).

Reduce your impact and support green hotels

While visiting the reef, prioritize staying with eco-friendly and green-certified hotels. (Look for a sustainability page or logo on the bottom of the hotel’s website.) Choosing reef-safe sunscreen and personal care products is also a must, as conventional sunscreens often contain chemicals like oxybenzone and octinoxate — contributors to coral bleaching and inhibitors of coral growth and regeneration, even at low levels. Using sunscreens without those products helps keep them out of the ocean. You can also look for more earth-safe toiletry items, like those from Stream2Sea, which are free of many of the most harmful chemicals. Rinsing off before you go in the ocean, especially if you have lotion or bug spray on, can also make noticeable difference.

Stay updated and demand accountability

Conditions on the reef can change quickly, so it’s best to stay up to date on reports from the Reef Authority, as well as local dive shop and tour operators. They’ll have the most real-time information on what areas are healthiest, or need some time off from visitors in order to recover.

Additionally, anyone who cares about saving reefs around the world should hold accountable the people, institutions, and industries with the greatest influence on reef health. Speaking up to lawmakers, voting for politicians who support climate-friendly policies, supporting and volunteering with ocean health non-profits, and supporting eco-friendly businesses can lead to long-term improvements in the overall health of the Great Barrier Reef.