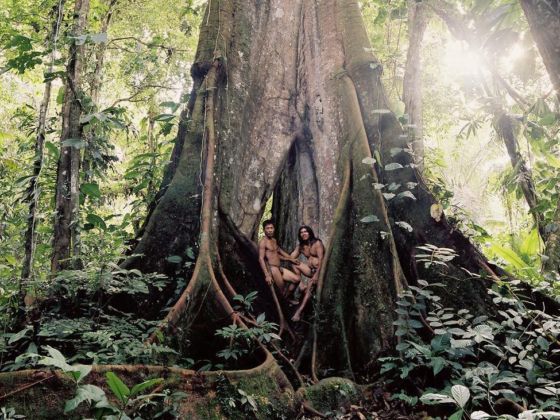

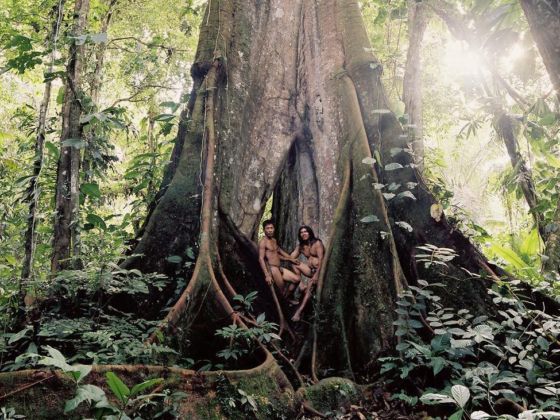

I spent a week in the Ecuadorian Amazon with some of the kindest and most resilient men, women and children that I’ve ever met. — the Waorani. A week isn’t long, and my grasp of the Wao language is limited. But it was enough to get a glimpse of what felt important, different and, perhaps, worth heeding: an approach to life that promotes pride, heritage, connectedness and what seemed an almost tangible sense of wellbeing. Here are the lessons I took away.

Lessons From the Jungle: a Week With an Amazonian Tribe

Learn by doing

I was surprised to see that the kids — some of the happiest, most relaxed and gentle-spirited children I’ve had the pleasure of hanging out with — would casually wander into the jungle to explore it their own way. Day-long — which would have most First World parents I know panicking — are the norm. When I asked about this, our guide asked, “How else will they learn the ways of the jungle?”

Living amongst, rather than protected from, the dangers that surround them is how the children cultivate instinct and survival skills. They learn by watching, feeling, hearing and being.

Only take what you need

The Waorani put a small net in the river near their settlement — and catch a handful of fish every couple of days to feed the community. They might also go out with a line and hook to catch one or two extra from a canoe, as needed. Other tribes, they told us, use plant poisons to kill hundreds of fish at a time in sections of the river. Traditional and natural, yes — but not the way the Waorani like to operate. They prefer to leave no trace.

They adopt a spirit of conscious co-operation with nature — never wanting to impact or alter the ecosystem in any lasting way. As I watched, the buzz of a US oil company’s chainsaws roared, not-too-distant, in the background.

Forget your age

The Waorani people don’t celebrate their birthdays. Our guide didn’t know his birthday, but thought he was around 47. He had never known his mother’s age, because she’d never known it herself.

It seemed that time and the passage of life is marked not so much by a number, as by experience — of the jungle and its teachings, and of life events like marriage or children. Age is something that is gathered up and nurtured with the passing of time, synonymous with knowledge and wisdom. It’s not a quietly resented number that’s notched up in years, prompting anxiety with the turn of each decade.

We out-siders could take something from this — if only a small reminder to reflect each year on the experience we’ve collected, and the insight and perspective that only time can enable. And, if we can, to hold that all-important number a little more lightly.

Let go: laugh

One afternoon I was clambering gingerly through a river, wincing as I walked on pebbles in bare feet, then flailing around to grab something as the current picked up. A girl my age sat on a rock nearby and started giggling. I looked up at her, and saw myself through her eyes. The two of us collapsed in fits of laughter (while I flailed more).

Instead of nudging her friend, pointing and sniggering, my new friend laughed kindly and openly. It was an invitation to connect, to play, to live with her in that moment.

What struck me, time and again, was how freely the Waorani are overcome with laughter — and how it comes from a place utterly without malice or self-consciousness. One look around a London tube carriage, filled with expressionless, downcast faces and suspicious side-glances — and us outsiders’ departure from simple, joyful human connection is plain to see.

Tell stories

The Waorani are a community under threat — their way of life and their environment are being attacked by the Western world in a way that leaves them fearing for their future.

Their line of defense is to share their lives, educate people on their customs, and perpetuate the knowledge and wisdom that they’ve cultivated and strengthened over thousands of years — through story. During my time in the rainforest, I heard many tales: of the Anaconda; of the King Vulture; of the Woodpecker; of childhood, of change, of long lost family. These stories weave together the threads of a cultural identity, and their telling and re-telling unite the people who share them.

Once thought to be the most dangerous and aggressive society on earth, the Waorani today protect their tribe’s future existence in a way that’s profoundly gentle and proactive, rather than attacking and reactive. When asked what they’d like us to take back home with us, to share with our friends and family, their answer was,“that we’re here. That we have a culture and way of life that’s different from yours, but sustains us in harmony with the ‘omede’ (jungle). We want to keep our identity.”

I can think of no better way to protect one’s identity than to share it with people. So, I’m writing this. Because the Waorani’s is a story that needs telling, so that a simple yet rich and nuanced way of life can continue.

Of course, most of this will never translate directly. I’m certainly not suggesting that city-dwelling pre-schoolers should be left to wander downtown city streets, or that we should do away with birthday cake. But, for my own part, I can’t help feeling there’s something in the spirit of the Waorani that I would do well to take away with me — to reconnect with, as a more ancient and grounded version of what it can mean to be.

This article originally appeared on Medium and is republished here with permission.