Forget searching for dreamy Airbnbs, epic hiking routes, and culinary delicacies — the first thing you want to look up when planning a trip is all the vaccines you need to get. Sure, it’s a lot less fun than planning an itinerary, but it can make or break your trip, and it’s not something you can leave to the last minute. To make sure your travel plans don’t turn into a prolonged visit to the local hospital, we asked expedition and wilderness medicine specialist Dr. Andrew Peacock to give us all the info travelers need to know about vaccinations and travel.

These Are the Travel Vaccines You Actually Need, According to an Expedition Doctor

Dr. Andrew Peacock has been practicing medicine for over 20 years. He works as an emergency doctor in Australia six months out of the year and as a wilderness and expedition medicine specialist the rest of the time. (Plus, he’s a pretty great adventure travel photographer). His focus when working on guided trips in India, as a ship doctor on expeditions to Antarctica, or leading treks in Nepal is prevention and risk reduction, so he knows the importance of having your vaccines up to date.

- General advice

- Main vaccinations for travelers

- Are any of the recommended injections superfluous?

- Where can you get your vaccines done?

- Can vaccinations make you feel ill?

- When does a vaccine need to be done? How long does the protection last?

- Proof of vaccination

- Diseases for which there is no vaccine, but for which travelers must be prepared

- Extra precautions travelers can take to remain healthy

General advice

Any US traveler considering a trip overseas must use two resources:

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. It is a very comprehensive and easy-to-understand platform with disease and country-specific details that for all types of travelers (long-term, short-term, pregnant, etc.). Dr. Peacock explains that he rarely recommend that patients check out the internet before consulting a doctor, but that the CDC website is an incredibly helpful resource that a traveler can trust.

- Their family physician. Volunteering three months in rural Uganda will not require the same medical advice as a two-day stay in Kampala, so a physician is the person travelers should turn to for their health-related needs in preparation for a trip.

Dr. Peacock explains that the biggest mistake travelers can make regarding vaccinations is ignoring recommendations entirely. The price involved in getting several vaccinations before traveling is well worth the investment. While it may suck to spend money on something you feel may not be needed, especially if you’re afraid of needles, it’ll cost you a lot more money in the long run if you end up getting sick while traveling and ruin your trip, so don’t skimp on immunization — no matter the cost.

Main vaccinations for travelers

1. Routine vaccinations

Whether you are traveling or staying home, the following routine vaccines are highly recommended for you and others to remain in good health:

- Measles-mumps-rubella (MMR)

- Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis

- Varicella (chickenpox)

- Polio

Note that even though these vaccines are commonly called “routine,” they are not to be dismissed, especially by travelers. For example, there have been outbreaks of diphtheria in many countries around the world in the past few years — including Yemen, Venezuela, and Myanmar — and several cases have been diagnosed in Australia. Diphtheria is a deadly disease that can be easily prevented thanks to vaccination.

If you’re not sure if you have been immunized for these diseases or if you think you are past the duration of protection, contact your family physician. They may have records of your past vaccinations if you don’t have a booklet to keep track.

2. Yellow fever

Yellow fever is a disease that is transmitted via the bite of an infected mosquito. Within three to six days, people infected with the yellow fever virus develop fever, chills, headache, joint and muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal and back pain, fatigue, and dehydration. In the most severe cases, the virus can lead to internal bleeding, organ failure, and the yellowing of the skin. Patients experiencing these serious symptoms will likely die within 10 to 14 days.

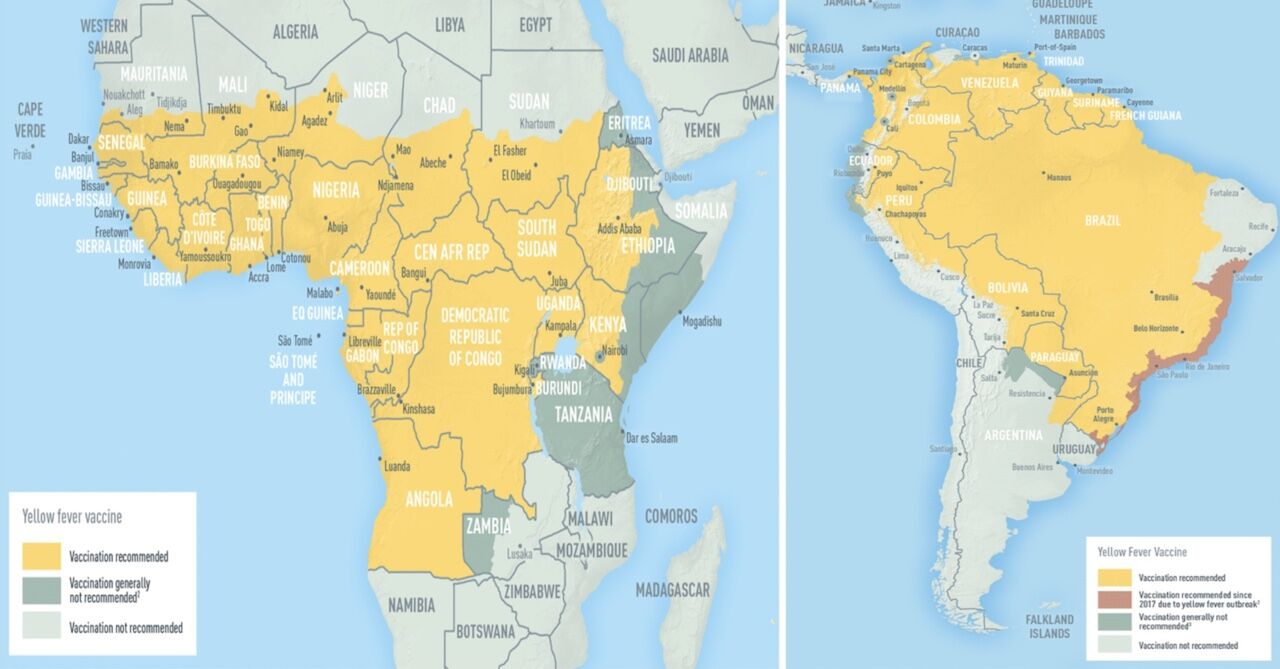

Yellow fever occurs in sub-Saharan Africa and Central and South America.

Photo: CDC

To avoid the international spread of this disease, some countries ask that all travelers show proof of yellow fever vaccination upon entering the country (Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Republic of the Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, French Guiana, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo and Uganda). Other countries require proof of vaccination only if travelers have been in a risk area. A full list updated in may 2021 is provided by World Health Organization here.

3. Typhoid

Typhoid is a foodborne and waterborne disease. Within three weeks, people infected with typhoid will experience fever, headache, constipation or diarrhea, fatigue, and loss of appetite. In more severe cases, Typhoid can lead to the enlargement of the liver and spleen or intestinal bleeding and can be fatal.

According to CDC, the highest risk of typhoid for travelers is in parts of Asia (mainly India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) although other areas of risk include Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America, and the Middle East. A good rule of thumb is that typhoid appears in countries where food and water sanitation is very poor.

The typhoid vaccine is only 50 percent to 80 percent effective, so you should be extremely careful of what you eat and drink when traveling to risk areas no matter what.

4. Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is a foodborne and waterborne disease. It can also be transmitted from the hands of a person with hepatitis A and, rarely, through sexual contact. Within one to two weeks, people infected with Hepatitis A will experience sudden fever, tiredness, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, and yellowing of the skin and eyes.

Hepatitis A is most common in countries with poor sanitation and food hygiene.

The vaccine is nearly 100 percent effective and requires two doses injected six months apart.

5. Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a contagious virus transmitted via blood, blood products, and other bodily fluids. People infected with the Hepatitis B virus develop a sudden fever, tiredness, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, dark urine, joint pain, and yellowing of the skin and eyes. Some people infected with the virus develop lifelong, chronic Hepatitis B. This can cause people to die early from liver disease and liver cancer.

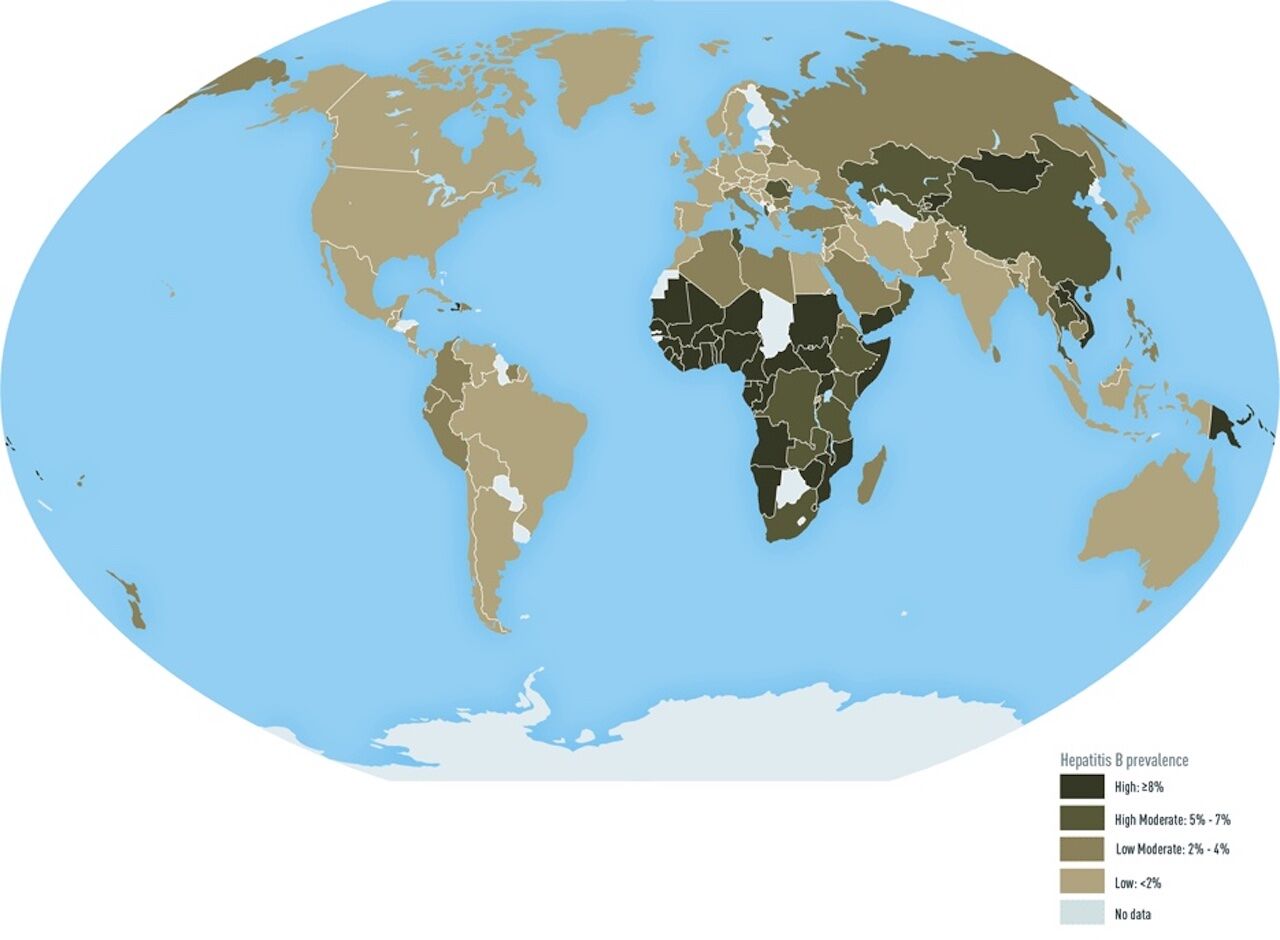

Countries with a prevalence of Hepatitis B infection:

Photo: CDC

The vaccine is between 98 and 100 percent effective and is a three-dose immunization; the second vaccine is given one month after the first dose, and the third dose is given six months after the first dose.

6. Cholera

Cholera is a severe intestinal infection caused by the ingestion of food and/or water contaminated with the cholera bacteria. People infected produce large amounts of watery diarrhea. The lost of fluid can be fatal, but drinking safe water to replace the lost fluids dramatically lowers the risk of death.

Travelers are rarely at risk of cholera unless they remain in high-risk areas for a long time and consume unsafe food and water.

There is active Cholera transmission in Benin, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Yemen.

The cholera vaccine is to be taken orally in a single dose at least 10 days before exposure to the bacteria.

7. Rabies

Rabies is transmitted through the saliva of a rabid animal (dogs, bats, monkeys, foxes, mongoose, raccoons, etc.). Humans usually get rabies after being licked, bitten, or scratched by an infected animal. Rabies affects the central nervous system, causing brain disease and death.

Rabies is found around the world except in Antarctica; however, risks are heightened in much of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America where rabid dogs are a problem.

Prevention is key for the rabies virus because once the symptoms appear, the disease is almost always fatal. The rabies vaccine is a is three-shot series (days zero, seven, and 21 or 28) given at least one month before travel to an at-risk area.

Whether you have been vaccinated against rabies or not, if you get bitten, licked, or scratched by an animal in a high-risk area, you should seek immediate treatment.

The best way to prevent rabies is not to approach animals, especially in high-risk areas. Symptoms of rabid animals are not always obvious, so remain extremely careful.

8. Japanese encephalitis

Japanese encephalitis is a disease transmitted by mosquito bites. Symptoms such as fever, headache, vomiting, confusion, and difficulty moving appear within five to 15 days. Japanese encephalitis can be fatal, and there is no treatment.

For most travelers to Asia, the risk of being infected by Japanese encephalitis is extremely low, but it varies based on destination, duration, season, and activities. Travelers who stay in rural areas for several months and spend a lot of time outdoors are the most at risk. Japanese encephalitis spreads during the summer and fall in temperate regions and year-round in tropical and subtropical areas of Southeast Asia, Health Canada explains on its website.

Photo: CDC

The Japanese encephalitis vaccine must be done at least six weeks before your departure. The immunization is done in two doses administered Seven to 28 days apart.

9. Meningococcal Disease

Meningococcal Disease is transmitted from person to person through droplets of respiratory or throat secretions. Kissing, sneezing, or coughing on someone, or sharing accommodations with an infected person facilitates the transmission. Symptoms include a stiff neck, high fever, sensitivity to light, confusion, headaches, and vomiting. Five to ten percent of patients die, typically within 24 to 48 hours after the start of symptoms.

Only those traveling long term to the meningitis belt in sub-Saharan Africa during the dry season (December through June) are at at risk and need to be vaccinated.

Photo: CDC

Note that Saudi Arabia requires participants in the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage to show proof of meningococcal vaccination.

It takes seven to 10 days after the injection for the vaccine to be fully effective.

10. COVID-19

COVID-19 is an infectious respiratory disease that spreads via “droplets and virus particles released into the air when an infected person breathes, talks, laughs, sings, coughs or sneezes,” John Hopkins Medicine’s website explains. The range of symptoms is wide and include fever, cough, sore throat, difficulty breathing, body aches, loss of taste or smell, runny nose, fatigue, vomiting, and diarrhea, among others. Symptoms may appear between two and 14 days after being infected. Some people only experience mild symptoms while others have severe ones that require hospitalization. COVID-19 can be fatal or lead to long-lasting health problems.

COVID-19 occurs throughout the world.

There are two type of COVID-19 vaccines available in the US: The Pfizer-BioNTech, the Moderna, and the Novavax COVID-19 vaccines.

Are any of the recommended injections superfluous?

Dr. Peacock explains that “before immunization, travelers must research about the diseases occurring in the countries they will be visiting and check if their travel plans put them at risk.” Only then can they make a serious decision about getting vaccinated.

Here is an example to illustrate the need for travelers to gather information before being vaccinated:

CDC recommends that some travelers to Madagascar get immunized against Hepatitis B. Hepatitis B is a contagious virus that is passed on through sexual contact, contaminated needles, and blood products. CDC recommends this vaccine if you might have sex with a new partner, get a tattoo or piercing, or have any medical procedures. If you don’t plan on doing any of the above while in Madagascar, you can argue that you needn’t be immunized. But Dr. Peacock explains that you never know when an emergency situation will require that you undergo a medical procedure that can lead to Hepatitis B contamination.

Where can you get your vaccinations done?

There are several locations where you can get your immunizations done. Some of the items on the list below will lead you to official websites that will allow you to find a place near you to get your vaccinations done.

- Family physician’s office

- Local Health Center

- Local Health Department

- Travel clinics

- Travelers’ health-specialized physicians

- Yellow fever vaccination clinics

- Local Pharmacies. Not all pharmacists are authorized to administer vaccinations, but it is worth asking your local pharmacist if your options are limited.

Can vaccinations make you feel ill?

It is not uncommon to get a localized reaction at the injection site (redness, irritation, swelling, bruising, etc.), but serious side effects are rare. Keep in mind that the risks from the diseases that vaccines prevent are much greater than the risk of vaccines’ side effects.

When does a vaccine need to be done? How long does the protection last?

The earlier, the better. Dr. Peacock recommends that you check out the CDC website and make an appointment with your physician as soon as you know when and where you are going, “even if your departure date is six months away.” The reasons behind the urgency are as follows:

- A vaccine asks your immune system to respond to the antigens injected by developing antibodies. But creating this defense does not happen overnight, so if you get your vaccines done only a week before you’re setting off, you may not be fully protected.

- Proof of yellow fever vaccine is only valid 10 days after the injection.

- Certain vaccines require several injections, some a few months apart. For example:

- Hepatitis A requires two doses injected six months apart to be as effective as possible.

- Hepatitis B is a three-dose vaccine. The second vaccine is given one month after the first dose and the third dose is given six months after the first dose.

- Rabies is three-shot series (days zero, seven, and 21 or 28) given at least one month before travel.

The duration of protection is vaccine-specific. Yellow fever is supposed to last a lifetime, but doctors recommend that you get a booster shot after 10 years. For typhoid, a booster shot is needed after two years. Do not assume that you are still protected against a disease if you were vaccinated against it a long time ago. Visit your physician to get a booster shot to make sure you are safe before traveling and ask them for a booklet where you can keep track of your vaccinations needs.

Proof of vaccination

Photo: Henrik Dolle/Shutterstock

Before you make an appointment to get immunized, try to locate your vaccination records (baby book, family physician, etc.). It will be very helpful for the physician to know what vaccinations you need. Also, make sure to ask the person administering your vaccines for a booklet where your vaccines and the dates of injections are listed. If you already have one, provide it so it gets updated.

Upon your first COVID-19 vaccination appointment, you should receive a CDC COVID-19 vaccination card displaying information such as the date of your immunization, the type of vaccine you were given, etc. If you have not received a CDC COVID-19 vaccination card, request one from your state health department or vaccination site and keep it safe and handy.

Certain countries require proof of yellow fever vaccination. Upon immunization, you should receive a yellow card called the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) to prove that you have had yellow fever vaccine. Note that the proof is only valid 10 days after the injection.

Dr. Peacock recommends that you bring your vaccination booklets with you, even if no proof of vaccination is necessary at your destination. The precaution can be very helpful in case of an emergency situation abroad.

Diseases for which there is no vaccine but travelers must be prepared

The two most common travel diseases for which there is no vaccination are:

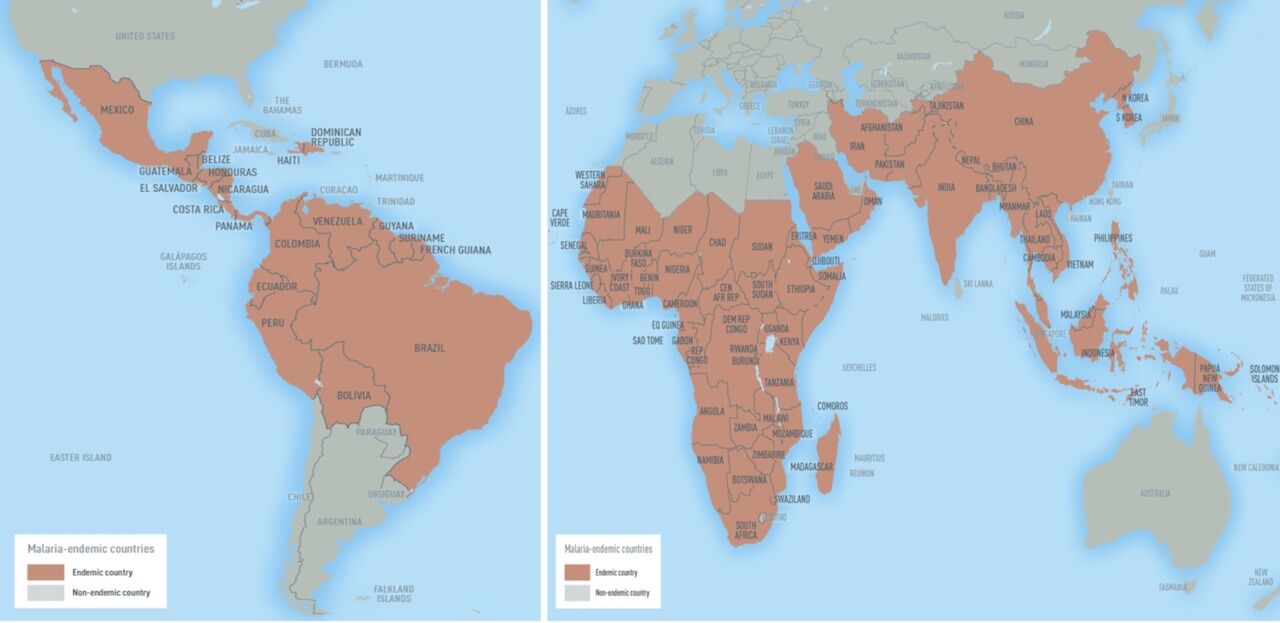

1. Malaria

On October 6, 2021, The World Health Organization approved a malaria vaccine called RTS,S/A01. The vaccine targets the most deadly and most common type of malaria in Africa: Plasmodium falciparum. It will first be rolled out to children in sub-saharan Africa.

Until the malaria vaccine is more widely available, there are several prescription medicines available to travelers who will visit countries at risk. Dr. Peacock states that not all malaria medication provokes unpleasant side effects as seems to be the rumor among travelers worldwide. There are several options available, and your doctor will help you navigate them according to your needs. Anti-malaria medication needs to be taken before, during, and after your trip, so, just like with vaccines, do not wait until the last minute to consult your physician about your travel health. Note that since malaria is a disease transmitted through mosquitoes, travelers should prevent mosquito bites by using repellent; covering their skin with long sleeves, long pants, and hats; using mosquito nets and staying in screened accommodations; staying indoors when mosquitoes are the most active, and using permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

Photo: CDC

2. Infectious diarrhea

Infectious diarrhea is a foodborne and/or waterborne infection. Travelers can do their best to prevent it by making sure the water they drink is boiled or treated and the food they eat is cooked and prepared with proper hygiene. According to Dr. Peacock, “Usually, infectious diarrhea resolve itself in four to five days, but can make you feel quite miserable.” There are antibiotics available that can treat the infection, so ask your physician about them before you set off. Note that Imodium does not treat the infection but will reduce the frequency of your stool in an effort to help control the symptoms. Do not take Imodium unless you need to (long bus rides, long flights, etc.) as it may prolong the problem.

Dengue, zika, and schistosomiasis, among others, are also diseases that currently cannot be prevented by vaccines. Travelers going to infected areas should look into the best behavior to adopt so as to remain safe. Consult the CDC’s list of diseases that can affect travelers here.

Extra precautions travelers can take to remain healthy

Prevent bug bites by:

- Using repellent

- Wearing long sleeves, long pants, and hats

- Using mosquito nets around your bed and stay in screened accommodations

- Staying indoor when mosquitoes are the most active at your destination

- Using permethrin-treated clothing and gear

Avoid your exposure to germs by:

- Avoiding close contacts with infected people (kissing, hugging, etc.)

- Wearing a face masks when in contact with strangers

- Avoiding crowds

- Not sharing food or drinks with others

- Washing your hand with soap or using hand sanitizer

- Not touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with your hands

Eat and drink safely by:

- Boiling or treating water before drinking, or drinking from sealed bottles only

- Eating fully-cooked and hot food from places with reputable hygienic practices

- Eating only fruits and vegetables that you can wash and peel yourself (if it’s washed with contaminated water, you will get sick)

- Eating and drinking only pasteurized dairy products

- Avoiding street food, if sanitation conditions are in question

- Putting ice in your drinks (ice made with contaminated water will get you sick)

Avoid sharing body fluids by:

- Using condoms or refraining from having sexual intercourse

- Not sharing food or drinks with others

- Avoiding tattoos, piercings, and acupuncture

Avoid non-sterile medical or cosmetic equipment by:

- Avoiding frequenting spas or beauty salons that seem unhygienic

- Avoiding tattoos, piercings, and unnecessary medical procedures