For most of us, the bogeyman lives under the bed or maybe in a closet, making unpredictable appearances when the house is dark and quiet. In Santa Fe, he comes out just once a year on the Friday before Labor Day. That’s when residents and visitors gather by the tens of thousands to stuff Santa Fe’s iconic bogeyman full of all their woes — overdue bills, divorce papers, eviction notices — and burn him up.

Santa Fe's Original Burning Man Just Turned 100. Here’s What It’s Like.

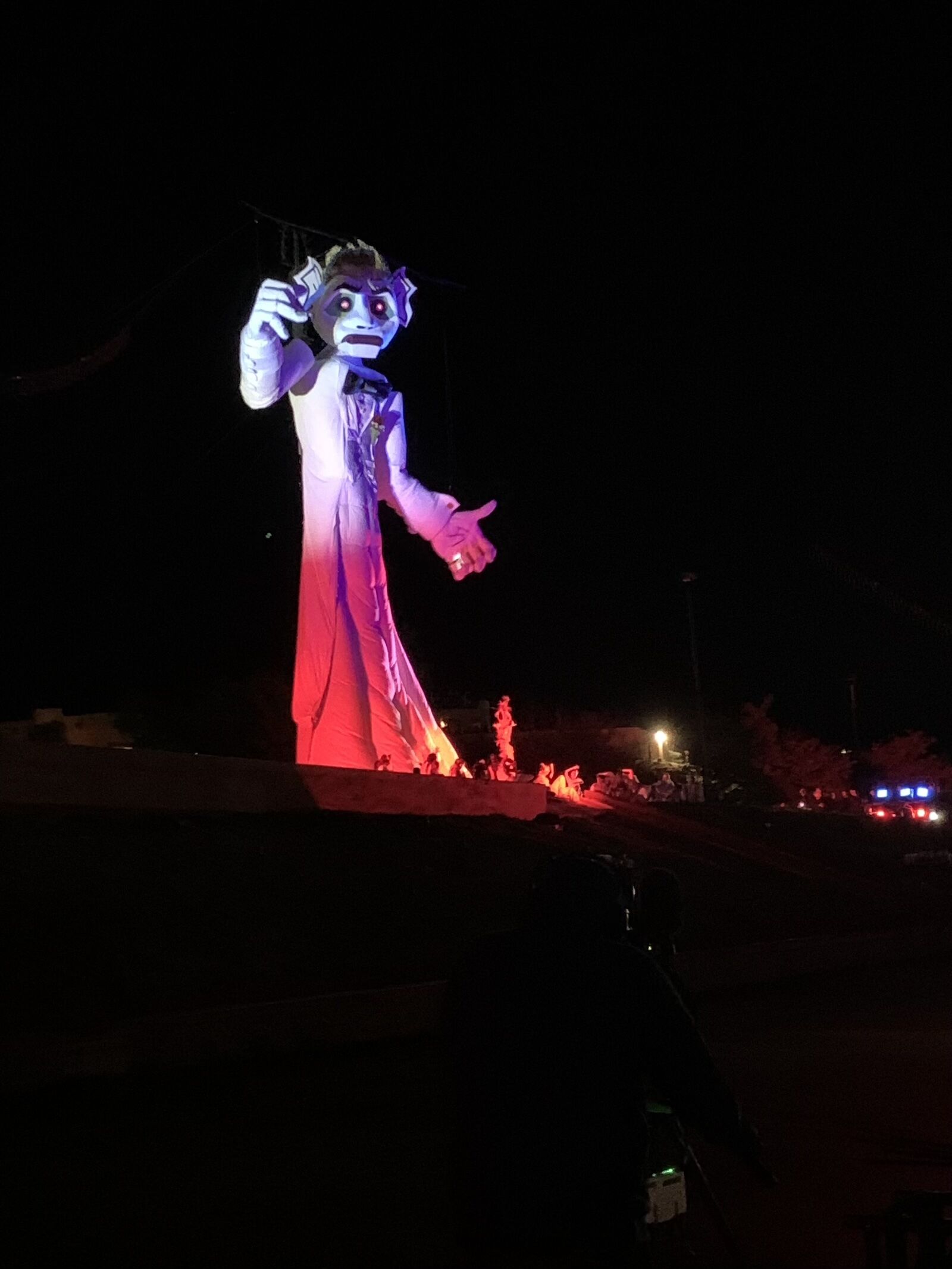

That’s a tough gig. But the bogeyman, a 50-foot-tall marionette called Zozobra, keeps coming back. In fact, the Zozobra festival turned 100 this year. It’s an integral part of life in Santa Fe, so much so that it’s taught in schools, occupies a place of pride in a large display inside the New Mexico History Museum, and draws crowds of community members throughout the day, whether they’re helping heft Zozobra’s giant body into place for the ceremonial burning or just enjoying the sight of seeing him assembled.

Gathering for the spectacle

Photo: Lisa Maloney

On the evening of this year’s Zozobra festival, a sell-out crowd of 65,000 people packed into the ball field at Fort Marcy Park for the bogeyman’s burning and all of the pageantry leading up to it. During the day, the scene was more relaxed, with hundreds of locals filtering through to witness the unveiling of a new Zozobra-shaped hot air balloon, then of Zozobra himself.

Zozobra is so large that he has to be trucked to the park in several pieces. He’s assembled on site and then raised onto the utility pole that will hold him with the help of a heavy-duty utility crane and dozens of volunteers, who heft his pliant body closer to the pole by main force as the crane takes up the slack.

Small crowds of schoolchildren, assembled on the grassy field below the cement stage where the marionette burns, chanted “Hang him up!” in their young, piping voices. They were eager to do their part in ensuring that Old Man Gloom, another name for Zozobra, goes up in flames to dismiss the community’s accumulated glooms, another name for the woes that have been stuffed into Zozobra’s body.

Photo: Lisa Maloney

No doubt, touches of humor help keep the Zozobra festival from descending into the macabre — like playing the Imperial March from Star Wars over loudspeakers as he’s raised up onto his scaffolding. But what struck me most about the festival was the community’s matter-of-fact and joyous acceptance of this embodiment of their distressers.

In many ways, the people of Santa Fe treat Zozobra as a beloved friend who shows up every year. They dress him in celebratory fashion: Last year he was dressed up like Lord Voldemort, the villain from the Harry Potter series, to celebrate the decade of the 20-teens. This year he showed up for his centennial in full formalwear with a bow tie, a boutonniere the size of an elementary schooler, and sparkling gold hair.

They also fete Zozobra — or perhaps the community that defies him, as the personification of all their woes — with hours of pageantry. This year’s act included fantastic young rappers from the Red Bull Batalla tour, dancing from the MaaTuu Pueblo Dancers, and performances from groups including Innastate, Black Pearl Band NM, and Mariachi Euforia.

The community lights a fire

Photo: Lisa Maloney

This year’s main event was unquestionably filled with the ceremonial trappings leading up to Zozobra’s flaming end, from the “gloomies” — community youth who capered at Zozobra’s feet as if he’d lured them to join the world of woes, until community adults menaced him to leave them alone — to the fire dancer in a towering red headdress who danced up and down the stairs at Zozobra’s feet with a flaming torch in each hand, tiny and defiant against his hulking form.

A choreographed light show of drones ticked down a countdown against the backdrop of the dark sky: 10 minutes until Zozobra burns. The drones spelled out “OLD MAN GLOOM” as Zozobra became increasingly restive, groaning and growling as would any monster carrying a whole year of the community’s hurts and glooms.

“BURN HIM,” the drones spelled out a few minutes later, answered by chants from the crowd. After 100 years, the people of Santa Fe know the answer: There’s no way that their accumulated woes from the year, no matter how weighty or menacing they may seem, can stand up to their collective desire to see them gone.

Photo: Lisa Maloney

The flame always wins out in the end, but it’s not the fire dancer who sets the first spark. Instead, someone pushes a button to set off incendiary charges that spray sparks from Zozobra’s body. In what might be the best possible advertisement for making sure you have fresh batteries in your household smoke alarms, it takes mere moments for Zozobra’s body of wood, wire, and fabric to be engulfed in flames.

His groans of fear turned to bellows of rage, arms waving and gesticulating as if he could shove the fire away. The illusion was made complete by the brightness of the flame set against the darkness of the night, conspiring to hide the crew of 15 animators in full fire gear who stood right behind Zozobra, hauling on heavy cables to move his arms, head, and mouth. One more animator was hidden in the crowd, using a remote control to direct Zozobra’s surprisingly expressive eyes.

And then, just a few minutes later, Zozobra was gone. His mostly fabric limbs and head crumbled to nothing, leaving only the wooden scaffolding of his body burning like a torch in the night. A couple minutes later that was gone, too, reduced to a bonfire on the cement… and then nothing.

Photo: Lisa Maloney

Visitors are allowed to contribute glooms to fill Zozobra. I couldn’t recall everything I’d scratched onto the dark sheets of paper I’d been given, except for the name of an ex who’d done me horribly wrong. But there was something deeply satisfying about knowing that everything I’d put into him was gone, riding into the night on the last of the flame and ash he’d generated.

You could feel the energy of the assembled crowd shift from intense focus to jubilation, aided and abetted by an impressively lengthy fireworks display. At least for tonight, we were freed from the weight of the world as we streamed toward the exits and into the dark, many wearing Zozobra t-shirts and other swag, or carrying miniature Zozobras as mementos.

Anyone who’s been on stage before knows there’s a certain catharsis in acting out theater and drama for others. But on that night, I witnessed something just a little different: It was as if all 65,000 people in the crowd had been just as integral to Zozobra’s defeat as those who openly defied him on stage. Together, with the force of our attention and through the proxies of the fire dancer and others who faced Zozobra for us, we had defeated the monster that lives under the bed.

Together we rise

Photo: Lisa Maloney

There is, of course, another layer to that sense of togetherness — the people whose year-round efforts transmute that community spirit into the concrete details of the festival. Although the Zozobra festival was originally conceived by artist Will Shuster and a committee of friends in the 1920s, its last 60 years have, with Shuster’s explicit blessing, been overseen by the Kiwanis Club of Santa Fe.

Any profit from the festival goes to fund nonprofits that support local children. But the festival also generates another layer of connection and support within the community, blending the slow thrum of long-time volunteers with a continuous stream of young people who’re eager to bring their skills and insight to keep the festival going. As anyone who’s ever run a nonprofit or organized a large event can tell you, there’s no better combination than this blending of old and new.

The invisible team of animators, bringing Zozobra to life as he burns practically on top of them, are a superb example of the human connections that knit together to make the festival go: They’re retirees, city employees, hospitality workers, and more. Many of them have been doing this for years — and the satisfaction of a job well done, and the community appreciation for their efforts, keeps them coming back.

“Zozobra has been a family tradition for me and my father for years,” explained Shannon Martinez, the animation assistant who moves Zozobra’s mouth. “We have both been part of the Zozobra family for 28 years.”

Martinez’s father is part of the crew that builds Zozobra and also directs the team of animators. He, meanwhile, first participated as a gloomy at 12 years old. After a few years of that he became a torchbearer, then a spotlight operator — and then 15 years ago, he joined the animation crew to help move Zozobra’s mouth, matching the live vocals created by a local judge.

I’m sure it’s that continuing injection of young blood, following trajectories like Martinez’s from gloomy to volunteer and then expert animator, that keeps the Zozobra festival evolving. Even as an outsider, it doesn’t take long to see how the festival shifts and changes to match the community’s journey over time, faithfully returning year after year to bear the town’s accumulated glooms back into the night.