THE FIRST TIME I met him nearly 20 years ago, I was a young record company intern marketing The Rollins Band’s End Of Silence album and tour (featuring a promising new band called Tool). Frankly, he was a bit of a dick, not just to me but to many of the fans who came to meet him at a Tower Records autograph session.

A few years later, hanging out backstage before a concert with the Beastie Boys, I realized he was also one of the funniest and most engaging storytellers I’d ever met.

We’ve probably done a half-dozen interviews over the past 15 years, including one in which I got so sick of his condescending attitude — he essentially accused me, and all other music journalists, of not knowing enough about music history to have a qualified opinion about current music — that I confronted him in a screaming match, ultimately challenging him to a mano a mano showdown of musical knowledge (between you and me, I’d have wiped the floor with him).

So it’s been surprising in recent years to watch the former Black Flag frontman evolve from punk’s grizzled elder statesman into a humbled world traveler.

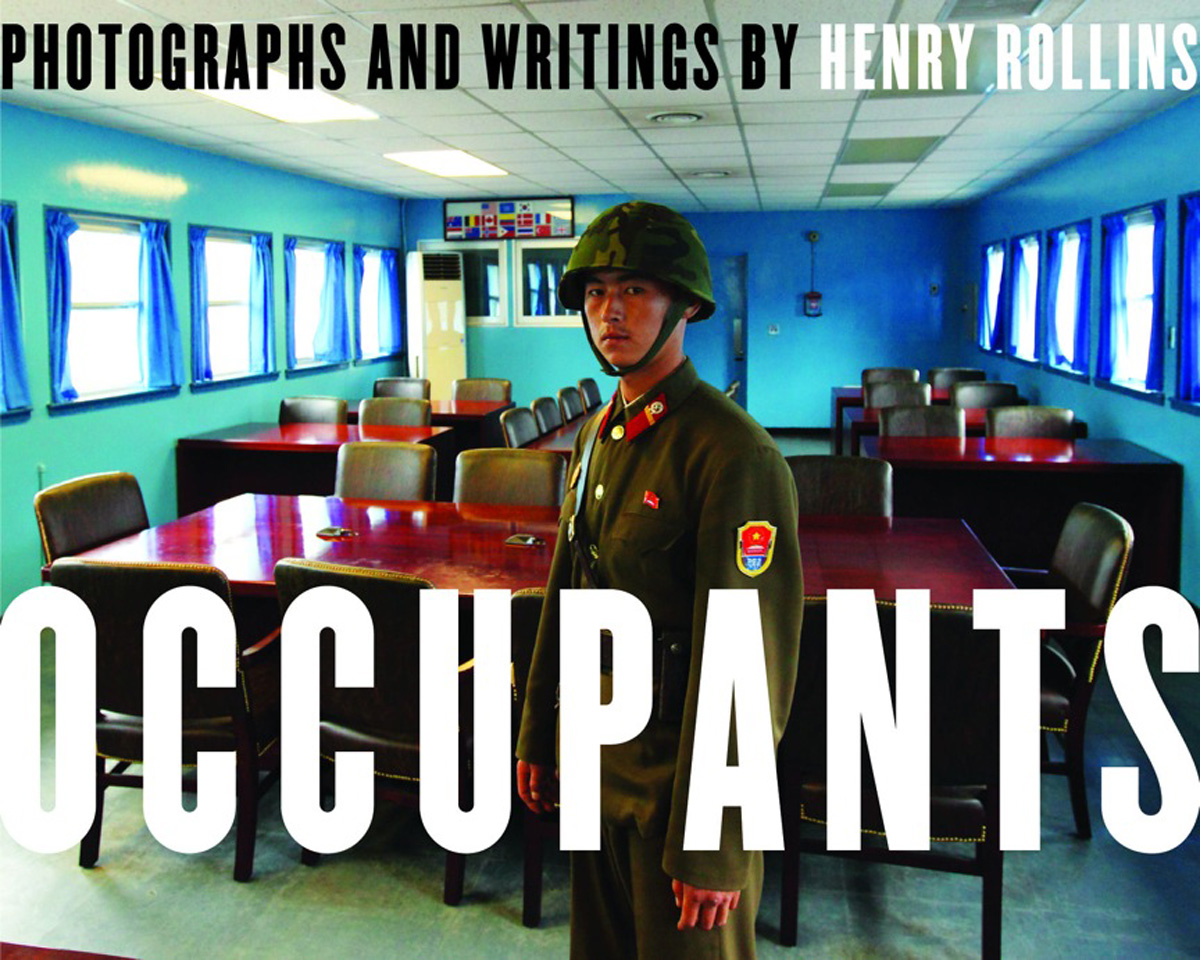

Intrigued by his National Geographic specials and the release of his new book of photos from his travels, “Occupants,” I decided to spend some time with this new, kinder, gentler Henry Rollins.

He remembered my name, but we didn’t discuss the disagreements we’d had in the past. In fact, this time we didn’t discuss music at all. Instead, we focused on the commonalities of our current careers, and our mutual passion for exploring the planet and its diverse array of cultures.

When did you first discover your love of travel?

My mom was an art nut, so she’d save her meager earnings from her government job and we’d go to museums all over the world. I’d been to Turkey, Greece, Spain, France, England and Jamaica before I was in the fourth grade. It gave me a taste for travel.

Garbage in Nepal sports a Minnie Mouse mask. This and all photos: Henry Rollins. Click for a larger view.

By age 20, I joined Black Flag and we became an internationally touring act. With the Rollins Band, I told those guys, “Let’s use this band as a vehicle to get places!” We played in Russia, Poland, Hungry, South America, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Singapore. I set a rule for myself a decade ago that I’m going to go to Africa once a year, so I’ve been to Africa 10 or 11 times. I’ve been to every country in the Middle East besides Oman and Yemen.

Have there been any trips that have had a profound impact or changed you in some way?

Oh yeah, the first trip to India was a real corner-turning experience for me. You see… not just poverty, but people who register as intolerably and unacceptably poor. They don’t feel sorry for themselves, so you look odd to them because of the way you’re looking at them. Since then, I’ve never thought about food, water, life or death the same. It was a very transformative experience.

Your new book has a lot of photographs from your travels to Southeast Asia. What were some of the highlights for you?

Yeah, I was in North Korea, China, Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan and North Vietnam. I wanted to see what was left of the bombings that Nixon and Kissinger unleashed upon the Vietnamese people. I wanted to go to the Northern Vietnamese war museums in Hanoi, so I hired a guide to drive me around.

He was an older guy who was in the Christmas bombings and he had amazing stories about taking his bicycle and having to walk over corpses in the street. He showed me a photo, and it looked like some futuristic apocalyptic scene — nothing but craters — from a B-52 strike. I asked if he could show me people afflicted with Agent Orange damage, so we went to a place called the Vietnamese Rainbow Village, which was started by an American Vietnam vet who saw what tetrachlorodibenzodioxin does to people.

He started this organization, funded by everything from Christian groups to European NGOs, to deal with ex-soldiers and their kids, who get this horrible mangling of their flesh from dioxin poisoning all these generations later. They allowed me to interview the director through a translator, and I interviewed a bunch of Vietnamese soldiers who were there for treatment, and they told me their stories. Half their kids are dead from Agent Orange. It was a very educational thing, and I’m hoping to get back there to do some documentary work.

Is it difficult to separate yourself from the sociopolitical issues? Are you ever able to relax and have a good time?

Just being in these places is good for me. One of the reasons I travel is this sociopolitical bent that I’m on: I want to see what globalization looks like on the other end. I want to see what global warming and climate change looks like all over the world.

I want to see what a war looks like after America has stopped talking about it, which is why I visited Southern Sudan. They had a war with the north for over two decades, so there are tank parts on the ground, bits of land mines everywhere and a huge mountain in the middle of a cornfield where they buried a bunch of Northern soldiers.

It was really intense to be walking over the bones and blood of this war that raged for 20 years. But try to find out anything about it in American newspapers…. there’s barely anything.

As somebody who grew following your music career, then your move into movies and talk shows, this seems like the next phase in your evolution. If I interview you again 10 years from now, where do you hope you’ll be?

I’d be very happy to be doing documentaries with my own production company as well as with National Geographic. I hold National Geographic in such high esteem. I think they’re amazing. I grew up near the building in DC, and I would love to be one of those older men in a pith helmet and a magnifying glass looking for some moth in a South American Rainforest for National Geographic. I think that would suit me very well.

So I’m hoping that 10 years from now I’ll be working on documentaries, writing travel books, taking photographs all over the world, and doing things to upgrade the way humans interact with each other, the way they’re cared for, and the way the environment is cared for.