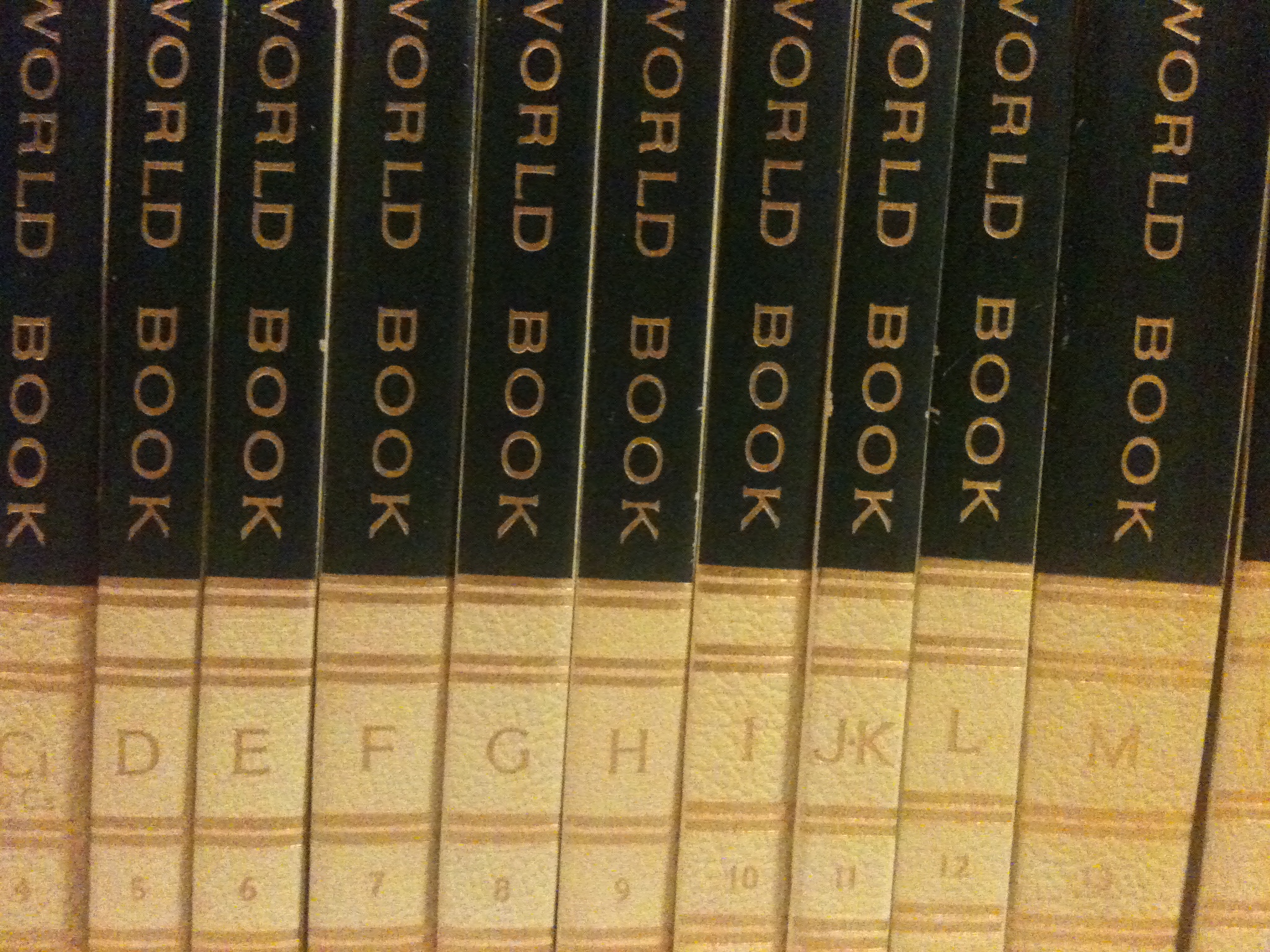

When I was five, my ninety-six year-old neighbor, Mr. Locke, died and left me a complete World Book encyclopedia set from 1964. Their weight was immense. The twenty-six hardcovers (A-Z, a dictionary, and a ‘Year Book’) couldn’t fit in a single box and were so heavy that even my dad had some trouble lifting them all at once. Like all encyclopedia sets, they were tacitly unreadable, like a phone book or a dictionary, but held mystery and prestige as fonts of complete knowledge and authority, so valuable they couldn’t even be checked out of the library. And I had one all to myself.

It was the only time in my life (including up until now) that I’d ever received something because of someone’s death. All I knew of him was that he was very old, and very old people died. Whatever that meant. Death’s shadow was blocked by unliftable boxes of leatherbound books with gold-gilded pages of probably every subject known to man, sorted by letter, Where should I start? Running my hands over the thick, rippled leather I started with my first initial, J, slightly bummed at its much-narrower build and that it had to share a book with K. It was nowhere near the robust volumes of M or S, but nonetheless filled with subjects like the Jurassic era, Judgment Day, and Jason (and the Argonauts)! Back then, those words and ideas and knowledge couldn’t arrive wirelessly from any computer or smartphone, only through the pure osmosis of old-school reading. It’s no wonder religions have always taken their books seriously.

As school projects requiring research became more numerous, I found myself increasingly drawn to the encyclopedia, and increasingly distracted by it, looking up hang-gliding while researching the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and learning about Surinam when I should have been reading about surgery. Yet unlike modern-day Wikipedia procrasination binges, the subjects weren’t linked by the text within each article, but by their alphabetical correspondence. Soybeans stood next to Space Travel, Nevada and Norway neighbored each other, and everything you wanted to know about lighthouses could be found directly before everything you could possibly know about principles of good lighting. Today, the knowledge that was once linear and alphabetical has become spread out, disarrayed, connected by the organic algorithms of habitual cross-referencing–much like the way our own neural synapses operate.

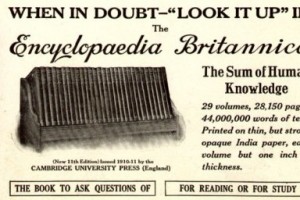

If you were to ask me twenty years ago, “Who wrote the encyclopedia?” I’d probably have laughed. Of course nobody wrote the encyclopedia. Authors names may have been buried beyond indexes and appendices, but to me the books simply were, like the Bible. They took authority from their very nature, existing out of thin air like newspapers and television, products so well manicured and tailored in their mass production so as to seem credible because they were in print.

To my five-year-old self, the biggest difference in the printed versus written word was that printed words were correct every single time: always clean, always straight. Handwriting could be crooked, leaning one way or another, error-prone, like the human it obviously came from. If it was in a book, it must have been true. And in my encyclopedias, published 29 years before I ever inhaled their unmistakable decaying must–that of a literary nursing home–outdated information told history as if it were happening in the present. Spain is a dictatorship. Skyscrapers were no higher than the Empire State Building. Segregation: [See “American Negro”].

During high school I volunteered to visit residents in a nearby retirement home where old and fragile men and women spoke of bygone eras and neglect and confusion. Everything about them was old and antiquated: their skin, clothes, taste in books and music, ideas, and their words. Yet they spoke and conversed relentlessly, never shy nor afraid to disagree. Like those often ignored wells of life experience, my encyclopedias remain continuously fixated on a past that’s sometimes at odds with the reality of the present, always incapable of presenting themselves as ‘modern,’ yet retaining an a visible aura of confidence.

But our encyclopedias and knowledge reservoirs are no longer unintentional time capsules. Our flow of information is now constantly subject-to-change and our ability to re-write stories, news, and facts so quickly enabled that history is no longer what has happened but merely what we believe to have happened at a given point. People, countries, and ideas are glorified, criminalized, and re-celebrated with such rapidity that an encyclopedia is now a bad investment not because it has a low shelf-life, but that it belongs on a shelf at all. Once the definition of authority, they’re now the epitome of proneness to error, the definitive take on what we thought…well, back then.

We no longer turn to encyclopedias, almanacs, dictionaries, phone books, or atlases as credibly curated compilations of what’s what in the world. Who needs a librarian when we’ve got Google?

I can’t imagine anything more mind-blowing to a person 100 years ago than a smartphone dialed into Google. One can imagine affluent aristocrats shipping a crate of Encyclopedia Britannica to their homes, waiting excitedly, as my five-year-old self did, to roam the wealth of the world’s knowledge. For them, information was expensive and prestigious, yet today it’s nearly free and open to anyone who can read and push buttons. Heated discussions were once settled with a journey to the library to consult the reference section; today, we just say ‘Fuck it, I’m Googling it,’ and it’s settled. Discussion over.

There is something mesmerizingly divine about Google that no other search engine has accomplished. Its simplistic layout centers the search box, placing the totality of the Internet before you like an infinite tome upon an empowering podium. Google’s multicolored, godlike branding looms reassuringly above, and every keystroke prompts a prediction of your query, as if a friendly librarian is saying, “Oh, let me get that for you.” And yet despite the fact that we can and do seize the opportunity to Google-check everything, are we more intelligent or more informed? What percentage of obscure Wikipedia articles do I actually remember?

Did I mention that every Wikipedia article eventually leads back to Philosophy?

The great difference of modern information is complete integration. You used to need about thirty big hardcover books to hold summaries of the world together; now a thumb drive will do. The circuitry of our electronics has become the motherboard of our existence, connecting everything by a series of clicks and backlinks like an omnidimensional interstate, continuously paving over the gravelly frontiers of the Internet’s outskirts, making it all whole and accounted for and one in a google. While it’s easy to portray the Internet as an unchartable cyberspace, our limited access to the predetermined routes of search engines both optimizes efficiency and standardizes the collective intake of information, much like the encyclopedias we’ve relegated to yard sales.

Yet despite my World Books’ obsolescence, it’s their outdatedness that charms and inspires me, reminding that the present, like the books themselves, aint what it once was. And it never will be.