Two days’ journey into the Ituri forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo, crouched low by a metal bridge over the Epulu River, I shot a handful of images as a man guided his cattle across at speed. A storm was rushing across the forest, pushing the warm air ahead of it in a wild wind that picked leaves and dust up into swirls and changed the light to a beautiful soft orange. I’d taken many photographs on many journeys before and afterwards, but the Epulu bridge image has remained one of my favourites.

It was also anything but trivial to produce. Hassling for visas to get into the eastern DRC, days of overland travel on crap transport, and no realistic plan in case of medical emergencies — it was something I’d had to think long and hard abut before committing to. It cost money. It was difficult. It wasn’t particularly safe. A few months after we left Epulu, the place was razed to the ground by a poacher’s militia that appeared from the forests.

To some degree, risk, expense, or hardship are the very DNA of exceptional travel photographs. When travelers increasingly carry decent cameras, and more and more of them are capable of better images, it becomes harder and harder to take the kinds of pictures that nobody else has. So you invest your resources — and possibly your safety — in trying to do genuinely original, valuable work.

On the road home from Epulu. As if to highlight the dangers of travelling so far off the beaten track. Photo: Richard Stupart

Which is why it is so surprising when organizations like the BBC and Getaway South Africa make grabs for your photographs, under the barely concealed bait of a competition to win an African safari.

On the surface of it, they are running a pretty sweet competition, in which you can win an African safari worth around $4,000 by simply sharing your favourite photo of Africa with them on Facebook.

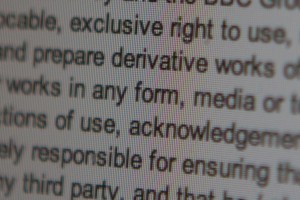

Except that by “share,” what they mean is “remove permanently to their stock archive.” Not license, not use-with-credit. Outright take, exclusively and forever, with neither acknowledgement nor payment. In their competition’s terms, such a one-sided form of licensing reads like this:

By uploading a photograph work to the website the Participant grants, or warrants that the rights holders of any contents, have granted Getaway and the BBC Group (and their authorised representatives) a worldwide, royalty free, perpetual, irrevocable, exclusive right to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, share, translate, distribute, exploit, sub‐licence and prepare derivative works of such photographic work (in whole or in part) and / or to incorporate it in other works in any form, media or technology now known or hereinafter developed, without compensation, restrictions of use, acknowledgement of source, accountability or liability.

Which is to say that by entering the competition, you give them your image for free and without requiring acknowledgement. Forever. And exclusively. As in, you may never have it published elsewhere.

While the level of screwing-of-travel-photographers by the BBC and Getaway in this instance is particularly and painfully eye-watering, they are in good company when it comes to serving up shiny competition prizes spiked with clauses that permanently strip parts of your archive. For new travel photographers (and indeed photographers of all kinds), this example highlights the risks of publication-via-competition. There are legit competitions out there, but it pays to do your homework and ask some basic questions before you enter:

Who is running this?

One time-tested way of smelling for fish is to ask yourself who is responsible for the competition, and why they’re running it. Any competition run by a stock image company, for example, should be treated with immediate suspicion.

With media companies, it can be harder to tell. While you would think the likes of the BBC — particularly as a publicly funded broadcaster — would be above hoarding other people’s work on totalitarian terms, that would appear not to be the case. Other brands, like National Geographic and The Guardian, tend to have much more integrity in their competitions’ rights requests.

What are the rights conditions?

Buried to varying degrees of depth in a competition’s terms and conditions will be at least one clause talking about you, the photographer / competition entrant, giving someone some rights. There might be other important stuff elsewhere (so read the whole thing), but dissect this particular clause closely — if there’s a fishlike flavour at this point, do not take these people’s candy. Walk away and go enter something else.

You especially want to pay attention to whether the license you give the organiser is exclusive or non-exclusive. Exclusive means you cannot license the photo to anyone else without the competition organiser’s permission ever again. Want to use it in a local newspaper? You need to ask them now. Want to sell prints? You need to ask them.

Next is to consider the broadness of the republication rights they’re asking for. A decent competition organiser might ask to be able to reproduce the photo, with credit, in all their media relating to the competition; i.e., they can use it insofar as it is a competition entry — they have not obtained the rights to use it in any context, anywhere. That’s a critical point. The limitation on using your image in media relating to the competition means you’re not giving it to them as stock art. You’re giving it only as a competition entry, and it may only be used / displayed / associated with the competition. Rights clauses that leave this part out want to use your image forever, wherever they want.

Then there is acknowledgement. If the competition organiser wants to use it without having to acknowledge you, they are looking for stock art. If your photo were simply a competition entry, it would matter to the organiser who took the photo, so that some of the possible outcomes (money, fame, or an African safari) could be sent your way. If you’re letting them show your work uncredited, any benefits it derives are usually structured to go elsewhere.

There’s more, but I’m not a lawyer, and that’s enough to probably pick up the worst culprits, since exploitative rights clauses tend to hang out in packs. If you find one of these claims, you’ll probably find its friends very close by.

Who else is entering this competition, or talking about it?

It would be great to discover an honest competition with a huge prize and nobody entering, but the truth is this doesn’t happen. Any decent image competition with a rocking prize and a great opportunity to showcase your work will usually generate some kind of buzz among other photographers. If you pick up that a competition you’re interested in is being completely ignored by competent, clued-up photographers, or has only mediocre entries, that’s probably a clue.

Which is not to say you shouldn’t enter a competition just because nobody better has yet. Just that you should do a little digging first, since it’s the metaphorical equivalent of a food stall that nobody’s eating at.

* Learn more in MatadorU’s Travel Photography program.