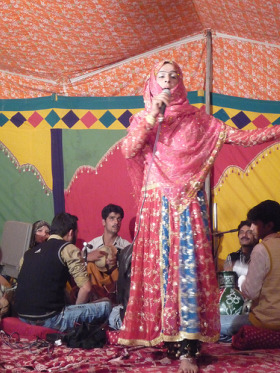

All photos by author

LATE ONE NIGHT, IN a rare moment when it was just the two of us, Sayma told me her story. I had only heard pieces of it before. She was the most modern in her family: she wore jeans, went out in public with her hair down, and talked on the phone with boys who were her friends. She’d even worked for a year in Delhi at a call center.