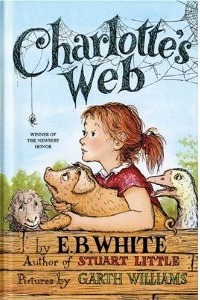

Photo: author.

When I told my mother, “I’m thinking about going to back to school,” her eyebrows bunched in confusion. This was years ago, when I had just graduated from college and was, in my parents’ eyes, living the American Dream. I was earning more money than my father, a machine operator, and I spent my days in a rolling office chair beneath the hum of an air conditioner and fluorescent lights.