The Kumbh Mela, believed to be the largest gathering of humanity on Earth, is a Hindu festival hosted every three years in a rotation of four different cities. The largest and most important iterations take place in Allahabad, India, at the Sangam, or confluence, of the Rivers Ganga, Yamuna, and the largely mythical Saraswati.

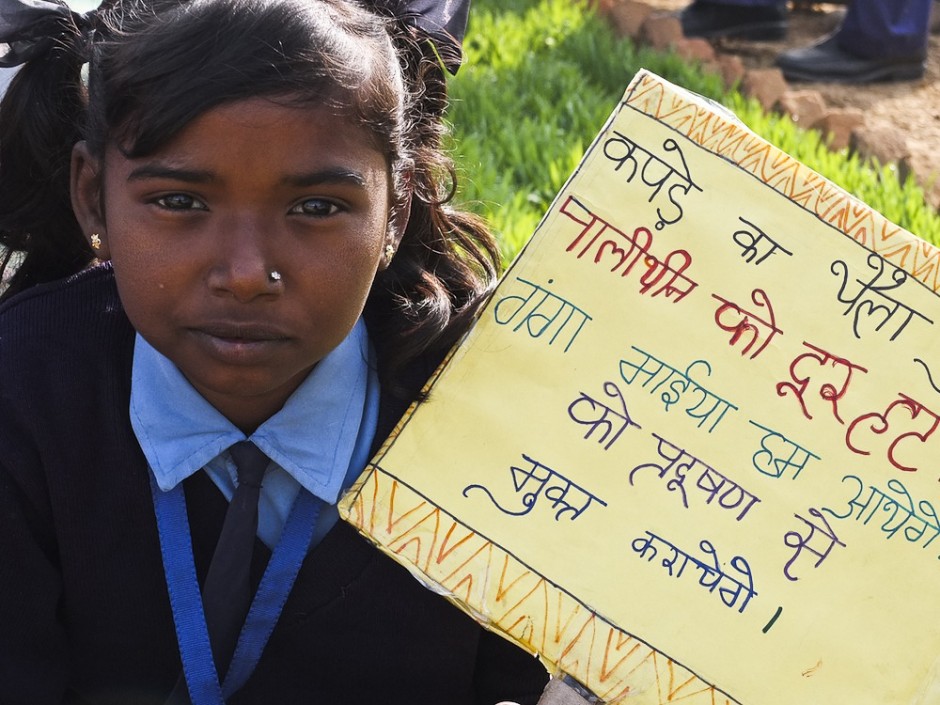

In January-February of this year, I found myself in a tent on the banks of the Sangam for a full month of the 55-day Mela, volunteering for an NGO working to clean up India’s rivers. Two months on, I still haven’t managed to get my head around this crazy / beautiful gathering of somewhere between 30 and 50 million people of various Hindu faiths. The following are some of my impressions.

Intermission

Intermission