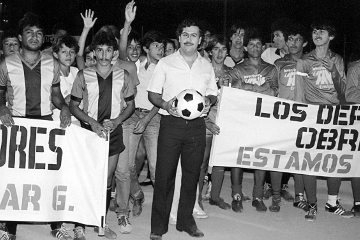

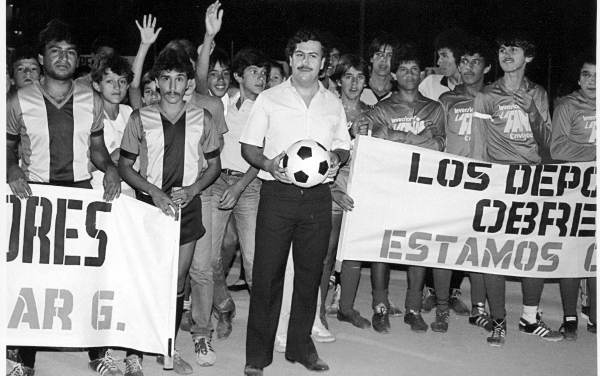

All photos courtesy of Jeff Zimbalist

Mitch Anderson: I’m going to start with the legend of Pablo Escobar…. From the film you get the sense that he was a kind of evil saint, responsible for so much death and corruption, but at the same time seen as a… savior of the poor. Who was Pablo Escobar?