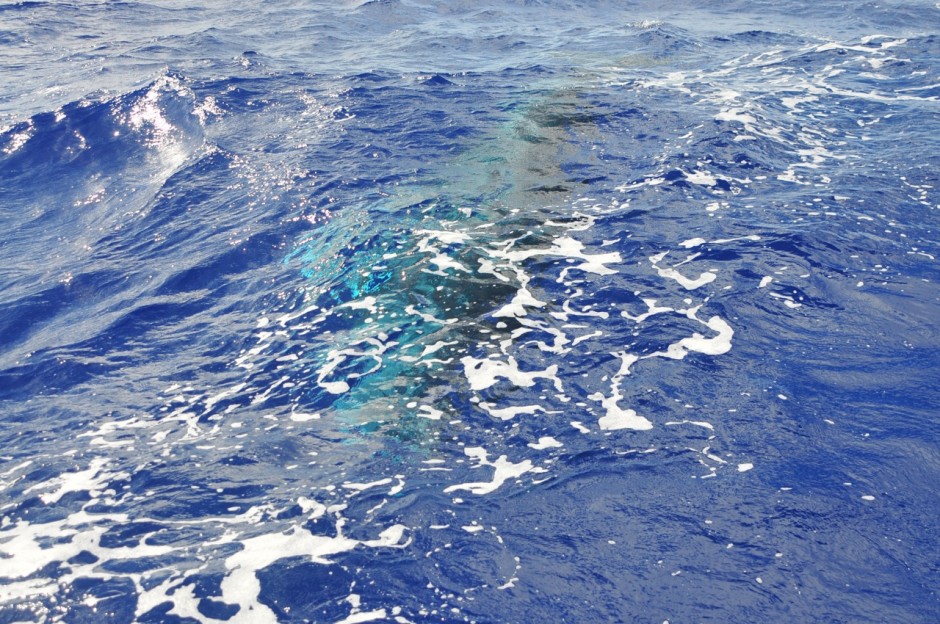

“THERE’S SOMETHING…really big in the water,” came the excited call from one of the passengers. Contrasting the deep blue of the surrounding sea, the whale’s belly appeared to radiate ultraviolet light as she rolled beneath the stern of our overloaded, decrepit charter vessel plodding slowly along as a result of torn sails. In Maori culture, the whale is a symbol of protection and a sign of safe passage over water, and with this is mind I rushed to get a glimpse of this twirling, playful creature. Scurrying past the fuel drums, stand-up paddle boards, life rafts, tires, banana bunches, crates, and coolers tied to the deck, I was enthralled by this whale, forgetting for a moment any warnings and uncertainties about the adventure that lay ahead.

We were sailing to a sparsely inhabited atoll, only 30-odd residents, with a month’s supplies and a team of seven as part of an expedition to study sea turtles. The atoll’s last research expedition occurred over a decade ago, performed by a team with a variety of marine research objectives. As with many islands in the South Pacific, transportation and weather remain paramount barriers for further research.

Palmerston is remote but not absolved of human influence, and to our surprise English is the residents’ first language. There are no stores, eateries, hotels, or hospitals. The island hadn’t seen a supply ship in over ten months and because of limited communication, we weren’t even sure they knew of our imminent arrival.

But at dusk, almost three days after leaving Rarotonga, we anchored. It was too late to navigate a dinghy through the narrow passage in the reef to the islets — or motu as they’re called locally — to get acquainted with our home for the next four weeks. Papa’a, or folks of European descent, have been welcomed on passing yachts for centuries, but it’s uncommon for a team to stay as we were planning to. We had permission, though, along with research permits, funding, transportation, a keen sense of adventure, and, most importantly, time.

First discovered by Captain James Cook in 1774 on a passing voyage, the island was named after Lord Palmerston. Almost a century later, in 1863, an English barrel maker and ship’s carpenter named William Masters annexed the island from the British government and settled on Palmerston with his two Polynesian wives. After adding a third wife to the mix, three distinct Marsters (as the name is now spelled) family lines were born, creating governance as colorful as their history.

I struggled to keep my excitement at bay as night quickly fell. The scenery was exactly what I’d imagined of a remote atoll in the South Pacific, with the moonlit glow of breaking waves misting silhouettes of densely packed palm trees on the horizon. There were no car headlights. No signs, streetlights, or flickers from airplane wings soaring above. Just a blanket of stars, a few planets, and the single light from our mast, swaying back and forth with the gentle rocking of the sea. We were floating just outside of the only true atoll in the southern Cook Islands — less than one square mile of total landmass and a vast turquoise lagoon surrounded by a ring of healthy reef. We could hardly wait to ditch our vessel and settle in.

We were here to study turtles, abolish rumors, live amongst our unique Polynesian hosts, and, most importantly, learn from our collective naiveté.

Intermission

Intermission

Intermission