WHEN THE FRENCH STREET ARTIST JR was awarded the TED Prize in 2011, he was asked to make a wish big enough to change the world. That day, he asked people to reveal their stories to the world by snapping photographs of themselves and pasting them to walls in public places in their cities:

Street Art Can Turn the World Inside Out

“I wish for you to stand up for what you care about by participating in a global art project, and together we’ll turn the world… INSIDE OUT.”

The prize was an honor many years in the making, recognition of six years of illegal street art projects that gave a voice and an image to communities who didn’t have enough leverage in society to do it themselves.

One of JR’s first large-scale projects, “Face to Face,” was organized in Israel and Palestine in 2006. He photographed taxi drivers, cooks, and lawyers who worked the same jobs on opposite sides of the Green Line, and pasted their images side by side in public spaces in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Ramallah.

People would watch him dubiously as he worked, and fall silent when he explained who was in the photographs. His favorite question to ask in this moment of silence was, “Can you tell who is who?” Most people couldn’t tell the Israeli from the Palestinian, and JR’s project became an early symbol of the silent majority in Israel and Palestine who see the humanity in the situation; who see that both sides are made up of people with jobs and families who want to live together in peace.

Six years ago, JR told the stories for them. His TED wish in 2011 was to see people tell their own stories. He asked people to take pictures of themselves and upload them to his Inside Out Project website. He printed the images on large posters and sent them back to the photographer, free of charge, with the request that they use it to tell a story about themselves, about their community, about a cause they believed strongly in. Within hours, people across the world were sending in photos.

JR sent posters to Tunisia, where people pasted their faces over billboards of Tunisian dictator Ben Ali during the social protests that sparked the Arab Spring. He sent posters to North Dakota, where members of the Dakota and Lakota tribes pasted pictures of generations of their people as a reminder to their city that Native American communities still exist in America.

He returned to Israel and Palestine, and set up a photography station in Davidka Square in the center of Jerusalem. There, supporters of a two-state solution could snap their pictures in a photo booth and have their poster printed instantaneously. These images of everyday people were soon plastered across the country, a striking project that demonstrated to Israel and the world just how many people want to live in peace.

The project was a way for people from Israel, Palestine, and across the world to turn the media’s narrative of conflict inside out, to expose the simple humanity of their communities.

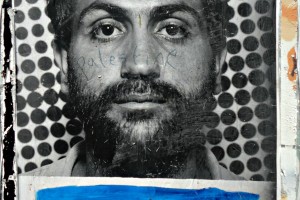

I was backpacking across Israel in September of 2011. It was around the time that JR’s photo booth rolled into town, and new portraits were popping up on the streets every day. The image of a Palestinian man pasted to the separation wall near Bethlehem is still rattling around in my head. His stare was an arresting break from the graffiti scrawl, a different glimpse into the Palestinian quest for recognition.

I imagine that posting his portrait was a way for this man to wrest control of his image from the conflict-hungry media, and to reclaim his role in the resistance movement from international street artists who try to tell his story for him. Witnessing his quiet, personal contribution answered the questions I was asking myself about the role that Westerners should play in the Palestinian narrative.

He stared back at me in the dry heat of a September afternoon, and told me that it wasn’t my story, or anyone else’s story to tell. It was his.