Casa Serpiente, or “Snake House,” is named for the way its undulant form twists through a tree-studded garden in Lima, Peru. It almost never rains in the Peruvian capital — the second-largest desert city in the world, after Cairo, Egypt — so trees are precious here. But this grove had even greater significance for its owners, a husband and wife named Irzio and Lisette. Irzio fondly remembers playing here as a child, when it was his parents’ backyard. So when the couple decided to build their new home in this green oasis, the husband recalls, “There was never any question: The trees had to stay.”

A restaurateur and entrepreneur, Irzio had acquired the family home, a 1940s colonial, years earlier. Now the couple’s idea was to turn the old structure into guest quarters, with offices downstairs for Lisette’s business (she’s a chef who owns an artisanal flatbread company). A vivacious blonde with wild curls and purple glasses, she explains, “I couldn’t have lived in that colonial unless I changed it radically: It just isn’t me.”

With her husband, she envisioned creating “something contemporary, surrounded by green, with lots of light and living spaces all on one floor.” They drew up a list of a dozen architects, pared it down to three firms, and commissioned proposals.

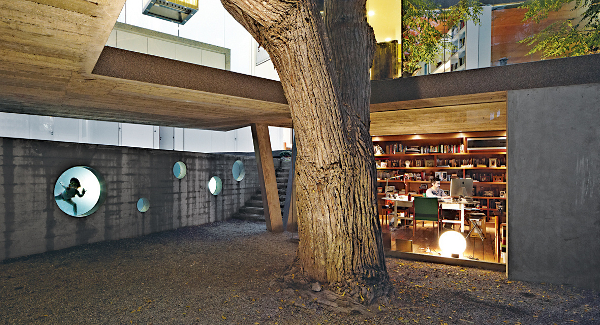

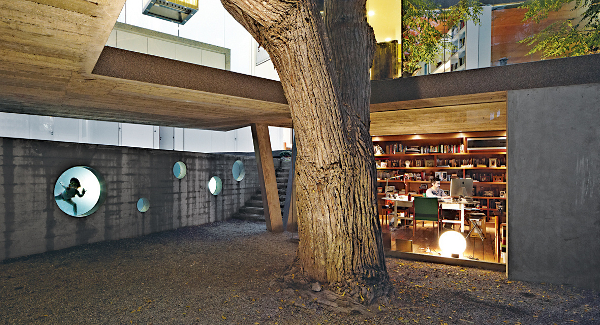

The most creative scheme came from 51-1 Arquitectos, a young Lima practice, headed by Manuel de Rivero, César Becerra, and Fernando Puente Arnao. It’s now a 21-architect firm, but, says Rivero, “That was one of our first projects.” Stringing together paper rectangles representing the desired programmatic elements, his team wound a long strip through the site model, dodging 25 existing trees. An occasional trunk poked right through the “house.”

It was an exciting proposal, “and clearly they understood us,” says Irzio. The couple soon hired 51-1 Arquitectos and then broke the news that, actually, they didn’t like curves. The architects then fashioned an angular “snake” that ramps up, generating its own rolling topography across the 15,000-square-foot yard.

A structural steel wall in the living area doubles as a built-in bookcase. The side chairs, floor lamps, and dining chairs were salvaged from the Hotel Crillón in Lima. The daybed and coffee table were designed by Maria Eugenia Alvarez-Calderón, who helped Irzio and Lisette with the interiors. The fireplace is from Fireorb and, as throughout, the floor is poured white acrylic by Química Suiza.

The L-shaped parcel allowed for independent buildings, old and new, with separate entrances from parallel streets. Hidden from view, Casa Serpiente leaves the traditional, upscale, residential streetscape untouched. Even the rear access is a stealth “James Bond entry” — Rivero’s description of the driveway that swoops through the original building’s archway, curving down into parking beneath the new house.

Equally sequestered, the front entrance stands back, behind a high enclosure. But inside the gates, playful openness reigns. One enters the 4,300-square-foot house via a long, wood-planked ramp, with flush lights sprinkled “like stars in the night sky,” says Lisette.

Inside, the pure white foyer leads, to one side, into a row of four bedrooms (for Clemencia, 15, Lorenzo, 14, and Gioia, 5, plus the couple’s master suite). To the other side, a glass-encased Melia tree appears. This open-ended box, lined in mirrored glass, performs like a kaleidoscope, amplifying the mature tree’s presence within the dining room. This room also overlooks a grassy courtyard, shaped by the coiling house. If the entry ramp is the snake’s tongue, its tail is the lap pool extending into this green space.

The walls are covered in Graniplast, a tinted acrylic finish. Nathan Pereira Arquitectos y Diseño advised on the facade, floors, and finishes. All the bedrooms are off one hallway; the three children’s rooms were designed by Vanessa Clark.

Remarkably, the serpentine form optimizes Lima’s peculiar weather patterns. A dense, stationary cloud covers the city much of the year, but, says Rivero, “shadows hardly ever appear, so there’s no better or worse orientation, just diffuse, vertical light” — which suits the building’s multiple exposures.

As this “snake” draws the garden indoors, the dining and living areas also merge. “It’s the exact opposite of most Latin American homes, with their compartmentalized, rarely inhabited living and dining rooms,” says Irzio. “These spaces are central to our everyday lives.”

Bordering the dining area (and separate from the main kitchen) is a work island, where Lisette can whip up family brunches, watch her children in the pool, or stage parties. “I don’t want to be in the kitchen, stirring the risotto by myself,” she says. “I want to be stirring and making cheers.”

From the garden, her open kitchen, sheathed in floor-to-ceiling glass, resembles a crystal cube — as does Irzio’s similarly encased study, tucked beneath the house’s primary level.

Well-placed transparencies and foliage balance Serpiente’s openness and privacy within the city, while the sinuous form invites internal cross- communication. Bubble-like portholes in the concrete swimming pool, for example, let underwater Gioia wave to her father in his study. “There’s a real sense of being connected,” says Lisette.

Seamless surfaces, like white epoxy floors, unify the winding structure. Against such neutral backdrops are infusions of intense color: The sunken family room’s mini-amphitheater is vermilion. Green tiles animate Lorenzo’s bathroom and vibrant orange his sisters’.

“I never imagined a house could generate the feelings of joy I’m experiencing,” Lisette emailed the 51-1 team. “From the dining room, I love watching my little daughter through the transparencies, run all the way from her bedroom. And it’s wonderful to sit beside the tree — taking in green inside and out — that gives me a sense of calm, of connection with nature.”

This story was written by Sarah Amelar and originally appeared under the title A Modern Concrete Home in Peru at Dwell, a Matador syndication partner.