August 2015 marked the start of my nineteenth year as a legal resident in the United States. I went to school for six of those years and have worked legally in the country for more than twelve years. I’ve helped build a company that has improved access to high quality, affordable healthcare for hundreds of thousands of Americans. I’ve helped create jobs on U.S. soil. I’ve helped modernize inpatient care for a health system that is world-renowned for its quality of care. Now, I lead pioneering work that enables healthcare providers to deliver care that focuses on prevention — something the U.S. healthcare system needs to reduce costs. But I’m still waiting for freedom — the freedom that only a green card can provide.

This Is What Waiting for an Employment-Based Green Card Looks Like

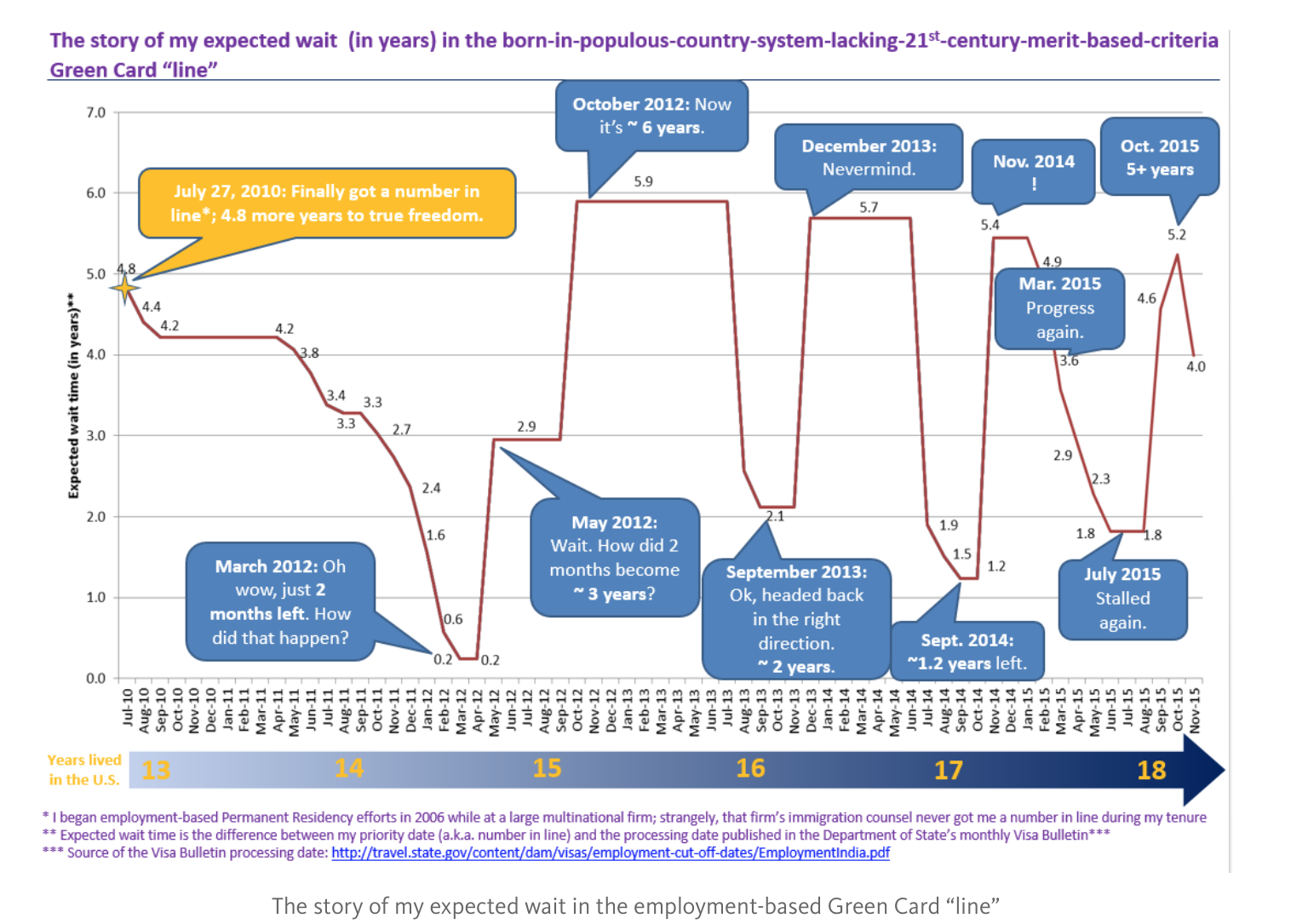

When people ask me how much longer I have to wait for a green card, I have this graphic ready to show them. This is what the “line” in the employment-based legal immigration system looks like. Depending on the month, my expected wait time for a green card could be two months — or six years.

As an analogy, imagine sitting at the DMV, waiting for your number to show up on the monitor. Let’s say your number is 100. The monitor shows 99, but then jumps back to 10. That would be frustrating right? That’s how the employment-based immigration “line” behaves. I guarantee you that if the line at the DMV worked the same way, people would be driving around without licenses, not driving, or riding around on bicycles with a megaphone telling others that the system is broken. I would likely be in the third category.

But the “line” above doesn’t tell my whole story.

I started the employment-based permanent residency process in 2006 while working for a top-tier management consulting firm. Strangely, their immigration counsel did not get me a number to wait in line during my tenure at that firm. While working for that firm, a client offered me to work directly for them. Had I accepted that offer in 2006 instead of sticking around, I would likely be a U.S. citizen by now. Friends who worked at other companies who started their process in 2006 became permanent residents in 2010 and 2011 and are U.S. citizens now. So it isn’t just a dysfunctional and outdated system that I’ve faced: questionable handling of my permanent residency application while working for a large multinational corporation set my freedom in this country back by several years as well.

Why is the wait so long?

After going to school here and contributing to the U.S. economy for over a decade, I’m still subjected to huge amounts of paperwork to stay in the country legally and still face the risk of self-deportation without ever having an opportunity to return to work here. Traveling overseas to visit family comes with the risk of not being able to return. The travel restrictions while I’ve been in the process have forced me to spend unreasonably long periods of time away from immediate family. For instance, I’ve gone almost two years without seeing my parents and almost three years without seeing my younger brother.

My most recent trip to India was a striking example of what I have to go through when visiting immediate family. Having spent almost 17 years without celebrating Diwali, a religious festival, with my family, I decided to break that trend and make an annual effort to visit them during the festival. This year, to make sure I could return to the United States, I had to make an appointment at the U.S. consulate in Chennai, India to attend an interview and get a visa stamp in my passport. That stamp would allow me to re-enter the United States to continue working. To get that stamp, I had to spend two days of my short visit to India in Chennai — a city where I have no friends or relatives. On the first day, I provided electronic fingerprints and got a photo taken. On the second day, I attended an interview carrying a pile of paperwork documenting my history in the United States. During the interview, the consular officer, who acted very professionally and had a kind demeanor, grimaced when he heard I was still waiting for my green card. Coincidentally, this was the same consulate where I attended an interview more than 18 years ago to get my student visa. Back then, I was excited to begin my journey. Never did I imagine that my legal pathway to citizenship would last more than 18 years and counting and that I’d be back at the same consulate renewing a work visa to extend my legal stay from 18 to 21 years.

Waiting in line also comes with incredible professional constraints, such as the inability to easily accept promotions and change jobs. I cannot start a company without risking self deportation. There have been years I’ve spent in underemployment because I could not change employers without having to restart key parts of the green card process from scratch.

Why is this wait so long? At this point, there’s one and only one reason why I’m still waiting and subjected to these constraints: because of where I was born. I cannot control where I was born any more than the color of my skin. Because the system judges me on country of birth and outdated merit-based criteria, coming from a populous country I’ve had to wait in line much, much longer than someone that was born in a less populous country like, say, Pakistan. In fact, had I been born in Pakistan, I would have been a permanent resident at least five years ago, and a citizen by now.

President Obama issued executive orders that will hopefully bring relief.

On November 20, 2014, President Obama announced executive orders aimed at modernizing and streamlining the legal immigration system. Those executive actions, when implemented, will provide more freedom to those like me caught in this archaic system; basic freedoms such as the ability to more easily change employers and accept promotions, allowing for greater contributions to the U.S. economy. While those executive orders have not yet been rolled out, I am hopeful that soon, I will have more freedom to advance my career.

But there’s more that can be done to make the system work better for the U.S. economy — and only Congress can do it.

America is at its best when individuals are at their best, and we need an immigration system that allows that. An immigration system that stimulates entrepreneurship and innovation — not one that facilitates indentured servitude and puts an immigrant at the mercy of questionable immigration counsel retained by a large corporation. A system that rewards immigrants for job creation through successful startups on U.S. soil — not just one that rewards immigrants at multinational corporations for creating jobs overseas. A system that retains the best and brightest graduating from U.S. universities — not one that increasingly drives them away to other countries that compete against us. And a system that strengthens the bond of family — not one that weakens it through unreasonable periods of forced separation.

The last major change to the high-skilled employment-based immigration system occurred in 1990; it is obsolete and does not meet the needs of U.S. Citizens nor the economy; and because it’s not a smart system, imposes injustice on certain skilled immigrants. It is time to update this archaic system. And that doesn’t necessarily mean letting in more high-skilled immigrants every year. The bar to qualify for a green card can be raised and the system can be made smarter without adding a single immigrant to the annual high-skilled employment-based green card quota.

There’s more that can be done to make the system work better for the U.S. economy and only Congress can do it. Go to my story on FWD.us to find out how you can push Congress to act.

This story first appeared on Medium and is republished here with permission.