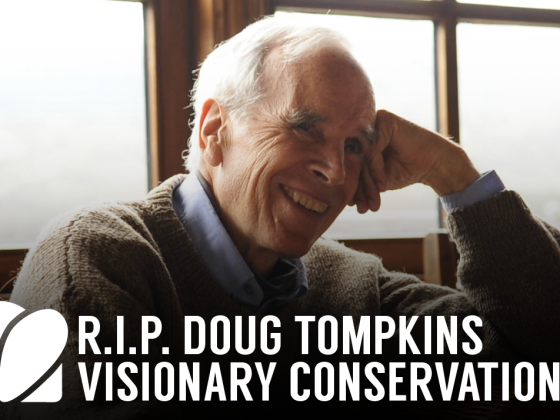

Four years ago, I found myself sitting across the table from Doug Tompkins. I was both psyched and intimidated. Leading up to the interview, our small crew–which included friend and fellow journalist Adam French as well as expedition photographer Claudio Vicuña–talked incessantly about Tompkins’s mountaineering exploits, his hundreds of millions earned as a gear and clothing magnate, and his radical approach to environmental activism and conservation.

That's What Activism Is: Conversations With the Late Doug Tompkins

From the email exchanges we’d had with support staff leading up to our journey, we knew face time with Doug could be challenging, elusive. He seemed like a person who wouldn’t waste time talking to you if he didn’t find you (or your questions) relevant or interesting.

And truth be told, our reception at the Future Patagonia National Park was a bit chilly. Doug nodded to us that first night at dinner, and noted that we’d have a bit of time in the morning. But we were definitely strangers here.

As luck would have it though, later that night we found Doug alone in the salon of the future Patagonia National Park headquarters, and struck up a conversation about climbing and paddling. Claudio and Adam, both experienced mountaineers, and myself–a lifelong whitewater kayaker, now had a bit of common ground. For half an hour, it was just the three of us talking about (but mainly listening) to tales of runs and first descents, epic near misses, and still unclimbed / unrun places throughout the Americas. Doug’s entire demeanor changed as got into the stories, an irrepressible fire coming into his eyes.

The next morning, as we got into the interview, Doug connected the dots between his childhood spent climbing and ski-racing and his lifelong progression with what he called “the nature tradition.” He remarked that becoming an activist wasn’t a sudden awakening, but a long path that included “much scholarship.” Eventually he galvanized his belief in the intrinsic worth (and need for preservation) of all life on Earth as “Deep Ecology,” (see the Foundation for Deep Ecology).

Discussing his decades-long work of privately purchasing tracks of wilderness in South America, rewilding them, then transfering them to the public as national parks, Tompkins referenced the tradition of national parks in the US. Both he and his wife Kris were super frank and humble about their legacy: “Long after we’re gone and forgotten, the land will be here.”

Doug Tompkins perished in a kayaking accident at age 72 on December 8, 2015. He was with lifelong friend Yvon Chouinard (founder of Patagonia) and several other close friends. He, along with his wife Kris, has protected more land than any other private individual in history.