THE ADAGE about that one teacher who changes people’s lives: This is Mark Warren. I’ve known him since I was a little kid at Camp High Meadows near Roswell, Georgia, and 30 years later, I see his legacy and influence playing out in dozens of people lucky enough to have been his students.

One thing that always fascinated me about Mark: Whenever you’re in his presence, it’s as if you’re in the presence of someone who has traveled through another time to be there. He’d always have some sort of animal pelt or bones or feathers, stone tools, arrows, cordage, something he was working on, studying.

But it was more than just what he had with him. It was about what he could “see.” It’s as if the “Georgia” he saw was infinitely wilder and more interesting than everyone else’s. Wherever you happened to be — a meadow, a strip of woodland next to a building, and / or especially in the woods — Mark could pinpoint traces of wildness — animal tracks, underworlds of fungi and insects, tree branches growing a certain a way — which led to stories and sudden glimpses of this “other” world. A dry creek bed that came to life after a thunderstorm, a piece of lichen slowly “eating” a rock, a deer’s path across a hillside — this world existed within its own time, its own pace. It did so right before your eyes (and all around you) but quietly, almost secretly, until you had patience enough to observe it.

Mark has dedicated his life to studying this world and practicing the skills — stalking, fire -, shelter-, and tool-making, as well as wildcrafting (harvesting plants for edible / medicinal purposes) — that are points of entry into it. As he’s pointed out, the culture of people living in this way (originally it was the Cherokee in this part of the world) is gone for now, but the wild plants once harvested for food and medicine still grow nearby, and “the foods still nourish; the medicines still heal.”

What I believe captivated us as Mark’s students — and certainly what makes his memoir Two Winters in a Tipi so emotive — is that he shows how living within this wildness is still a possibility. That despite all of our technological development, nature and the wild persists — and always will.

Over the last couple of weeks, Mark and I corresponded via email about the book. I sincerely hope everyone reads it.

DM: Although the evolution of “tipi-life” forms the narrative backbone of Two Winters in a Tipi, in many ways it’s also a kind of love story, a portrait of the relationship between a man and his dog. It seems this story couldn’t have happened without Elly. She wasn’t just your companion, but as you pointed in out in many places, your teacher. How did living in a tipi change your relationship with her?

MW: Elly and I already enjoyed a powerful pre-tipi bond. I had found her in the woods during an electrical storm. As a young puppy all alone, she was so frightened by what was going on around her that she was trembling to the point of self-injury.

By gathering her up in my arms I suppose I was branded her savior in her mind. Our close relationship began during that stormy moment. Her eyes would forever say “thank you” from that day on … every time she looked at me.

What changed for me when the house-fire took everything was my forced “demotion” to her subsistence level — which, I would learn, was no demotion at all. It was, in fact, a transcendence. She carried her complete life with her everywhere she went. It took losing my possessions to really understand that.

When I stepped out of the mainstream onto her path, I immediately sensed the privilege. Our partnership became richer. I sense that most dogs revere their owners like a god, or perhaps a (hopefully) benevolent dictator. Elly and I probably retained some version of that theme simply because I could make food materialize in her bowl, but we moved closer to the peer relationship in tipi life.

When we pulled up in my truck to the smoking ruins of the house, her complete indifference to the loss struck me as an edifying moment. She just took her sentry spot and plopped down and lived in her moment. After circling the rubble a few times, I took her lead and did the same. We were alive … together … and we had everything we needed. It was a lightness of being that I had never before experienced. In fact, secretly, I felt that the fire had somehow blessed me. I would revisit that same theme as I advanced in survival skills and would strike out for self-imposed survival trips, but those excursions were only week-long. Elly’s lesson was more lasting.

Because she shunned the tipi as a sleeping abode, there was always the immutable lesson that I would never truly catch up to her autonomy. (She may have been part coyote, in fact. She looked it.) Although my life’s work would be all about that kind of self-sufficiency (as a survival teacher), it would never come as effortlessly to me as it did to her. (It takes me four hours to construct a winter-proof, rain-proof shelter. Elly could curl up in leaves within seconds.) Simply put, I admired her as much as I loved her.

I know that every dog owner has a similar emotion and probably says what I am about to say here: She was profoundly unique. People always commented on it. She seemed human. Though an exemplary athlete, she was the calmest dog I’ve ever known. She went to schools with me when I did programs for students. That was back in the days when such species intermingling was possible in a public or private facility. (Now she would not only be denied entrance but probably strip-searched and X-rayed.) She was always the best behaved body in the classroom.

There is one very physical aspect that I have to mention. When I got serious about learning tracking, Elly became my textbook and teaching aid. Learning gaits is part of tracking — to know when an animal speeds up or slows down … and why. I probably paid more attention to my dog-companion’s feet than any dog-owner in history so that I could learn the track patterns left in those transitions: from stalk, to same-side walking, to diagonal walking, fast walk, trot, lope, bound, and gallop.

It’s a lot harder than one might imagine. Just seeing the paws touch down and trying to memorize the pattern can be too much for many pet owners. I know because I’ve tried to help others learn to observe these gaits as their pets perform them. Invariably, they give up out of frustration.

At one point in a class, I rolled out a long ream of paper and painted Elly’s feet different colors. We spent the day with her moving through different scenarios, leaving multicolored prints. It was an invaluable experience for all who witnessed it. Though if one had asked her … it had been an exercise in patience and tolerance. As I painted her feet, she looked off into the distance and tried to appear noble. Every now and again she turned to face me, her expression saying, “I will do this for you, but you’re not going to tell other dogs, are you?” I never did it to her again.

And last, this tidbit: She loved to canoe with me, even in whitewater. (Up to class three.) And know this: She learned to read the water. I watched her lean the proper way in the bow as we approached a particular move in complicated currents. She was the perfect partner. We never had an argument.

I believe you (Elly’s learning to read water). I believe we experience relationships with our dogs that reveal things that seem “pre-language” or what some might call supernatural. It’s as if dogs hold our vestigial bond to wildness. For example, my dog knows when I’m planning to take him on an adventure. He knows it even before there’s visible evidence — packing, etc. He just senses it.

To me this connection to or remembrance of our (nearly forgotten) relationship with the ancient world is the primary message of Two Winters. The “ancient world” is still with us every day — but the skill required to inhabit it, to achieve autonomy (ability to create fire, shelter, knowledge of plants, animals, skills for procuring food) is less a means to an end — akin to being able to survive a plane crash — less a kind of “extreme sport” (as popularized by reality TV shows and personalities like Bear Grylls) — than a practice which ultimately leads to the possibility of transcendence. Is learning to “survive” essentially a spiritual act?

It would be a mistake for me to answer that with a “yes” or “no.” The concept is complicated. “Survival,” as the public tends to think of it, is autonomy in the wild — especially when thrown into an emergency scenario. Such a hapless survivor is faced with solving all his/her problems and satisfying basic needs by a new set of rules, which are, in fact, the oldest set of rules in the world: Man lives by the gifts of the Earth.

Most of us live on a very superficial level geared toward ease and comfort — getting our foods from stores and restaurants, achieving heat by adjusting a thermostat, cleaning ourselves by stepping into a special stall with a supply of hot water. I’m in this category, too.

In survival mode, a shelter must be made. In winter, such a construction takes me 4 hours working at a dedicated pace. Foods must be identified, harvested, cooked for better nutrient availability. Since we no longer possess the instincts of Paleo-man concerning plants, we must academically learn all about botany (which, in my opinion, is the single most important study to address for a survival student). A person trying to rely on a sense of intuition about such things is likely to die by eating the wrong plant. (Even domestic animals have lost this skill to identify natural foods. The wild animals still have it.)

I have spent 40 years studying plant edibles and medicinals, and I am still scratching the surface. (But without that 40 years of study, I could not teach what I teach [survival] nor could I go on self-imposed survival trips.)

Creating fire by friction is a very physical act, based on a knowledge of form and materials. I have experimented with countless materials which I deemed promising for fire; and many, many times I have merely learned what does NOT work.

So, there is a very physical, even ambitious, side to survival. Quite frankly, very few of the survival students who come to my school are physically prepared for one day of work. They usually do not complete their winter shelters because 1.) it’s a LOT of work and they know they don’t have to finish it. (For safety, they bring a tent for backup. I can’t force them to sleep in the shelter…) and 2.) they are not physically prepared for a day’s work.

Their vocations usually are not as physically demanding. (It is interesting that few people with truly physically demanding jobs sign up for survival classes.)

With all that said, however, look what the Cherokee did when harvesting a plant. They circled it 4 times (a sacred number), approached it from the south (there was a reason), spoke to the plant, gave it a gift, and then carefully took what they needed … if … the resource was plentiful enough. This is most definitely a spiritual act. They knew then what we are just now learning through science — that plants are sentient beings with sensory potential and communication capabilities. There is actually a conversation that goes on between humans and plants — even if the human does not speak. It happens through pheromones.

The Cherokees’ behavior with plants and animals can be described as reverence and gratitude. Speaking to a plant is not so very different from saying grace before a meal.

What I have learned or gleaned, perhaps, from my life in the forest is that how I go about doing something matters to me as much as what I am doing. To go about my tasks in survival is work. It is also part of the conversation between man and nature and the Maker of All Things. How I go about my day keeps me in sync with the larger picture. I am not a Cherokee, so I do not follow the Cherokee sacred formula. But I have adopted my own way of interacting with plants and animals — much of it, I have to say, emulates the Native American. They had it right.

Survival, when you think about it, is the oldest way of being. It’s actually the norm, in terms of fundamental life on Earth. It’s odd (and dangerous, perhaps) that we have moved so far from that mode of living to the point of losing that lore. I’m not laying blame here. I understand the development of technology and marvel at it (and gratefully use it). I often think of human history as the Evolution of Comfort. It’s a natural inclination to figure out ways to make work easier.

But the cold truth is: What most consider “the real world” could fall flat on its face. The “really real world” (hint: it’s green) cannot. Arguably, it will always be. (And if it isn’t, neither shall we.)

All this hoopla like the TV show “Survivor” and “Bear Grylls” and “Eco-Challenges” … they’re just entertainment. Some of it a combination soap opera/game show/voyeurism experience; some are trying to thrill/shock you; others are pure sports.

Some might actually be good. I don’t know because I don’t watch any of them. (Okay, I watched one of each of the above at the request of my students.) There’s nothing wrong with these genres, as long as you are aware of what you’re watching. In my opinion, they miss the mark on the essence of survival. They have no heart, and they seem to have no clue that the Earth is one big cornucopia basket — usable only with know-how.

One of the most resonant themes to me throughout Two Winters is travel. Your students travel to and from Medicine Bow — you note these arrivals and departures as favorite moments. You travel to different schools to teach, and the return to the tipi becomes a ritual. But more than travel in the context of distance, there’s a sense your inhabiting “the really real world” is a journey not unlike stepping into a different land or even a different time. Exploring it via what you call a “spiral path.” Your connection grows so strong that to leave it, you experience disjunction. You write:

If I take a job in a distant state, step onto an airplane, and touch my feet back to Earth a thousand miles from home, at the core of me I feel utter disconnection, as if I have somehow cheated myself of earning the distance. If I fly far enough, I meet people who speak a different tongue, and the disjointedness of the journey turns it bathetic. To ground myself, all I know to do is to start spiraling again to learn this new place and perhaps think of it as another life, another beginning place.

What’s an example of this “spiraling” in a place far away from Georgia, or outside the US altogether?

Travel — or perhaps, not traveling — is an important topic to me. I don’t like being a part of the concept that teaches children that they must travel away from home in order to really engage nature. Such trips often become flash-in-the-pan exercises … entertainment … guaranteed excitement from a predictably “arranged teaching aid.” Sometimes in these cases nature is little more than the backdrop for some anticipated event. Like a zip line, a whitewater rush, etc.

Here’s how that lesson translates into adulthood: I have a physician friend who lives here in the Appalachians, where we are surrounded by thousands of acres of National Forest. This part of our state is famous for its hunting opportunities, yet he flies to Montana or Colorado or Idaho, where a guide meets him and leads him to the particular animal he is anxious to kill that season.

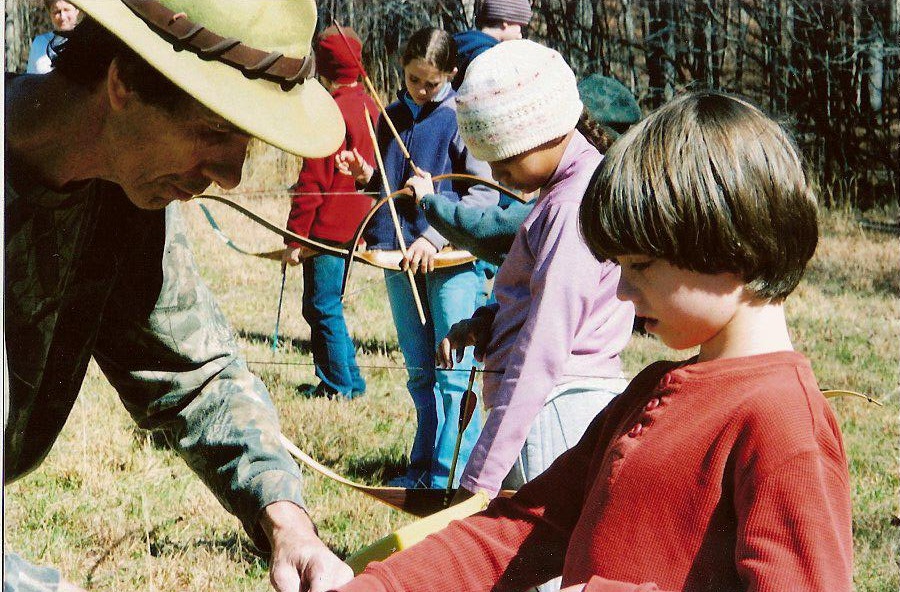

All these venues have some place in nature education because they are fun. I believe you’ve got to have fun in nature to appreciate it. Then from appreciation, there hopefully follows regard … and finally conservation. I know I may sound contradictory here, but I feel so strongly that the new generations are missing the miracles at hand, close by. This is why I like to travel — to get to their place … to show them that there was adventure in their backyard all along.

Often when I present a Native American program at a school, I convince the teacher to let me take the class outside. I have really geared my own learning agenda to be able to “astound” them with what is there. In essence, we travel back in time and see their strips of woods and fence line of weeds as the everyday resources of the Cherokee or Muskogee, depending on where their school is located. They marvel at wild foods like the inner bark of some trees, at the medicine from dogwood that can cure a migraine or the succulent plant by the creek that never fails to stop an itch. We make cordage from tulip trees, animal calls using acorns, and fire from wood we twirl between our palms — that latter one, by the way, is my strongest contender to keep up with Six Flags.

As for my need to learn land in piecemeal excursions, what could be more natural? It is how all humans once connected their experiences into some kind of sense and memory and logic. The world is full of seams, connecting one biome to another. These are the transition areas that wild animals love to frequent. It is the stitch mark of biodiversity. I simply think that passing through them is important. Otherwise, experiencing nature is a little like opening a book to a random page each time you try to read it … and expecting to see the story within.

The spiral is a good path for me, because then I don’t have to walk a linear path that misses so much else. In a way I am exploring a sunburst of paths from the origin point. You could look at a spiral that way. It is the sunburst woven by a golden thread.

I once took a job in western Washington State to teach a private survival class. When I stepped off the plane I had been exempt from the Tennessee Valley, the Cumberland Plateau, the Mississippi corridor, the Ozarks, the Great Plains, the Rockies, the Great Basin, the Cascades and who knows what else. In this single leap across a continent I plopped down like a sycamore seed that had blown to Venus.

Before I could start teaching, I had to walk, to expand outward to see exactly where I was. How could I do that by choosing one direction? As best I could, I learned a 40 acre domain that would serve as our sphere of resources, gifts, and terrain. Only then could I begin. My attitude that week was that this forest was my sole realm of existence and that I was soaking up as much of it as I could, to make it feel like my home.

Finally Mark, for those of us who’ll likely never have the opportunity to spend a winter in a tipi, and for those for whom the distractions, the pulls for “entertainment,” for travel away from our home grounds, are so strong, how can we find — even for a moment — this adventure in our backyards? Are there simple habits or games or explorations you recommend?

I suggest making an outpost in your backyard or nearby wooded lot, if you have that capability … and if it is safe. This structure of sticks can be easily made. Find two stout forked sticks that will hold up a crossbar log and lean this against two trees. That gives you a horizontal ridge pole against which to lean a”fencing” of sticks like a fortress wall. This place will serve as a blind in which you can disappear to observe whatever animal life thrives around you.

Dawn and dusk will be the best observation times, so entering the blind should be planned an hour before either. Once inside, be still, be quiet. Take a foam pad to sit on for comfort, for warmth in winter, or for protection from chiggers if you reside in chigger country. What a great adventure this can be with your child. Eventually let this place be a cookout site. If you are in a strictly urban area, this opportunity may not be available. You may have to use a friend’s land.

One of the most easily harvested wild foods falls from oak trees. It’s exciting to prepare food direct from nature, because it harkens back to history and allows you to relive it to a degree. Gather acorns, remove the cap and discard, crack the shell, remove the shell, and with a knife blade held perpendicularly scrape away any rind attached to the nut. This rind will be orange or reddish brown.

Place each half of the nut flat side down on a cutting board and cut the thinnest slices you can. Now boil water (but don’t boil the acorns). Pour the just-boiled water over the acorn slices in a bowl. Let stand for 5 minutes. Pour off the tan-tinted water and then pour into the bowl more just-boiled water (keep your pot boiling for handy refills). Repeat this process as many times as needed until the water does not turn a tan color anymore.

To make this a positive experience, mix a little brown sugar and melted butter with the nuts. It’s dessert time.

And last, try your hand at stalking a wild animal. It’s all about extreme slowness, never moving any part of the body beyond snail speed. When you think you have the balance and patience and strength for it, you’re ready for your first challenge. There is a stumpy, little black cricket that scuttles around through the lawns of much of America. He’s about an inch and a half long and doesn’t fly. Called a field cricket. You’ve heard his chirp a thousand times.

If you can pinpoint one with your ears, stalk to it. If you stalk well, the cricket will continue chirping and you can actually see the interesting way that he makes his sound. (It’s not the way you think!) If you are too hasty or impatient, the cricket will go silent and you’ll not learn his secret.

For more information, or to take classes from Mark Warren, please visit Medicine Bow. You can order Two Winters in a Tipi at Amazon.