Shacklands. Riemvasmaak, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Riemvasmaak is a four-year-old informal settlement technically known as Extension 29. The name means “to tighten your belt.” All images courtesy of the author.

Shacklands. Riemvasmaak, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Riemvasmaak is a four-year-old informal settlement technically known as Extension 29. The name means “to tighten your belt.” All images courtesy of the author.

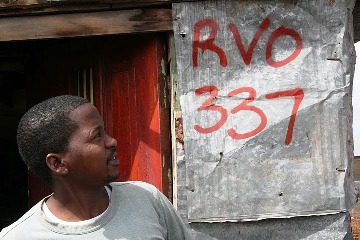

SPRAYPAINTED above the window on warped scrap metal are the house’s dimensions: 3.2 x 3.7. On each side, old addresses from previous government administrations have been marked by the Department of Human Settlement. RVO 337 is a classic “shack”: metal walls and roof rusting at each edge. A single wooden door to the right of the windows allows a manageable space for entry before wedging between the laminate floor and plywood ceiling. A full-size bed, complete with decorative duvet and pillow covers, dominates the single room. The wallpaper features newspaper from 2008. The only additional adornments are three framed photos of 50 Cent.

As there is very little furniture in the shack, and no dresser or drawers of any kind, Themba hammered a few nails into the wall for me to hang my belongings. Two pieces of my luggage hang at the end of the bed next to my jacket. Every so often, I return home to find more objects suspended carefully from nails at various spots around the interior. He recently hung his tools—a crowbar, measuring tape, and handsaw—in the corner at the end of the couch, just over the area where we take turns sleeping.

The couch serves multiple purposes, one as Themba’s filing cabinet. Lifting a cushion is like opening a drawer on a piece of his life. Under one is information he picked up from a job fair. Under another is clothing from a recent female visitor.

Themba is meticulous about making the bed in the morning. Stripping the bedding from the couch, rolling up blankets, and placing throw pillows, he takes quite a bit of time refining the appearance of his home.

RVO 337 is not your average bachelor pad, being largely a place of transience. Themba has been “commuting” for two years from this shack in Riemvasmaak to his parent’s house in neighboring Izinyoka for food, clothing, and bathing. Amenities are limited to a basin inside for bathing, and a recently acquired “primer” stove, with which I’ve nearly set the house on fire each morning. The toilet, which is outside in the dirt yard, consists of three walls and a shelf above a bucket. There is no roof, which makes it ideal for stargazing, but an unpopular spot during storms. I consistently bash my forehead against the two-by-four bracing the door.

When he speaks, Themba considers each sentence and repeats his phrases slowly. “You are welcome here. (Pause). You are welcome.” He honored me by bestowing upon me a Xhosa name, Elethu. He explained that it forms a piece of his full name, Thembalethu, symbolizing that we were brothers. The literal meaning is “our hope.”

I moved to the township after becoming frustrated with the lack of accessibility to different cultures and contexts in Cape Town. I felt unfulfilled and unchallenged. After almost a year in South Africa, I had a nagging feeling that I had missed something important. I felt like an athlete who trains for the big match and shows up at the stadium to find he must sit the bench. I wanted to experience more of South Africa, in a deeper, more meaningful way. Thus, I left the city of the two oceans for the shacklands of the Eastern Cape.

Riemvasmaak is a four-year-old informal settlement technically known as Extension 29. The name means “to tighten your belt.” Residents tell me this signifies their knack for survival, which quickly becomes evident. The township is affectionately known to residents as “Riempi.”

Dusty, rocky paths are the salient feature of Riemvasmaak. The rocks present formidable obstacles to walking around at night, yet are convenient ammunition against the mangy, malnourished dogs that tend to block passage. During particularly strong rains, the paths turn to whitewater. Metal wires are strewn about at every conceivable location and angle to dry laundry and, as it is explained to me by those who have hung them, to harass potential thieves. Visibility at night is limited to the full moon and the glow from steep floodlights up the hill in neighboring “formal” townships.

The legacy of apartheid is still alive in the spatial dynamics of urban and exurban residential areas, which functionally means that Xhosa live in black townships, Coloured live in coloured townships, and whites live somewhere completely different. A “mixed” township, Riempi infringes on those barriers. Before a recent protest march, the community chairman noticed that all the signs had been written in English or Afrikaans. He instructed Themba to make a few signs in Xhosa to accurately represent the people.

Often, I find it challenging to distinguish Xhosa from Coloured, and thus I struggle to know which language to use for greeting. I tried to explain this to Themba. In what has become a ritual in my debriefing, he shakes his head. “No, man,” he chuckles. “Here in the Eastern Cape, the Xhosa guys and the Coloured guys are mixing their vocabulary.” The “tsotsitaal,” is universal.

Maria’s house is the one with the wheelbarrow on top. For weeks, it was the only way I could find it. I borrowed it a few weeks ago to start a garden, heaving her eight year old son onto the roof to shove it down. When I was ready to return it, I couldn’t find my way back to the house.

Maria lives at the end of a row that includes two of her three sisters. Between the three of them, they have seven children ranging from 4 months to 9 years. The adults drag the kids from one house to the next, while the children drag little plastic baggies of chips and toy chain saws. Describing her approach to parenting, Maria says, “Bend a tree while it’s young.”

When her mother died, Maria’s father kicked her and her sisters out of the house. “We decided to move to an informal settlement so that we’d appreciate a brick house when we got one. When I look at that house, I’ll say, ‘that’s my house’—and I’ll appreciate it.” I ask her why she thinks people move to informal settlements. “Because they don’t have any other choice,” she states.

Though in outward appearances, Maria’s shack is of the same mold as Themba’s, inside it is altogether different. Thin patches of carpeting are covered by a roomful of furniture, which is needed to accommodate her many and frequent guests. There is a small couch that can fit up to three people, a cushioned chair for a couple more, and two beds, one larger for mother and father, plus a small one for the two kids that during the day is pressed into service as another sitting area. The cardboard and plywood walls house two windows with ornate dressing, and can scarcely be recognized behind a houseful of appliances. They have many things a “wealthy” family would desire—stove, oven, refrigerator, washing machine, even an old PC which her husband uses to play fighting games when he returns from work.

To run the various appliances, Maria contacted a woman up the hill in a “formal” settlement and offered her R 80 per week to connect to her electrical supply. This symbiotic relationship provides the unemployed woman with an income and Maria’s family with electricity. Electric wiring runs up and over three rows of shacks, a tarred road, and down again to link into the electricity of a brick house in the nearby township of Kleinskool. On any given road, you are likely to see tangles of wiring at your feet crossing intersections.

There is no running water. Riemvasmaak has seven outdoor taps scattered through the community and available to everyone. The water is clean and potable. For a family of four (and all of her guests), Maria makes an errand for water about every other day. She fills six ten-liter jugs of water that the family uses for cooking, bathing, washing up, and any other imaginable need. Two of the jugs are stored on the counter next to a plastic basin. Except for the initial effort of retrieving water and the end result of dumping the water outside, this seems to function very nearly like a sink in Glendale, Illinois. The washing machine is filled and emptied manually.

Whereas Themba’s toilet facilities lack a door, Maria’s toilet, perched between her house and her sister’s, has a proper address. Two brass numerals left over from a previous life announce that this is #33. I ask her if I can have my mail sent here.