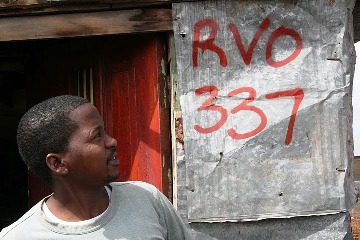

Themba

Back in the house, Themba sits underneath a headline that reads, The World’s Most Famous Escape Artist and tells me about his plans for a family. His “future wife,” Disa, has given him a 10-month-old daughter named Liefie. He refers to Disa as “Future” to distinguish from “Beyoncé,” “Gorgeous,” and his many other girlfriends. Bewildered, I ask him about this paradox. He grins mischievously and explains “it’s just how we do things.” Later, he tells me the story of one of his friends who “doesn’t like girls.” I was eager to hear about his peer group’s acceptance of this individual and the level of community tolerance, but before I could ask any questions, Themba elaborated. “He stays with the same girl all the time.”